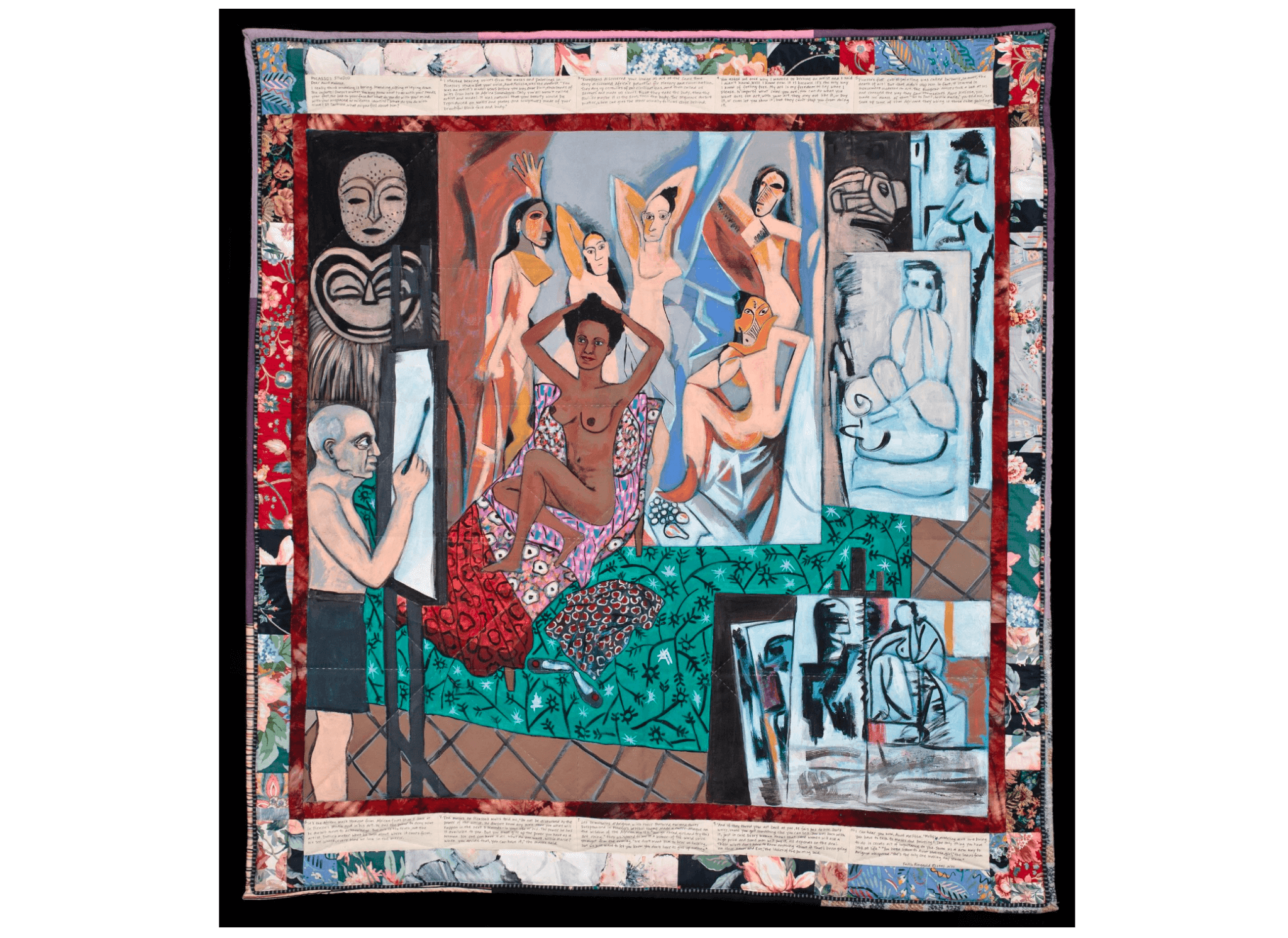

In 1991, Faith Ringgold created a story quilt entitled Picasso’s Studio, her revisionist interpretation of Picasso’s painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), as part of her French Collection series. In Ringgold’s version, she recreates the infamous scene with the five abstracted prostitutes but at the center of the quilt features Willia—a fictional Black woman the artist often uses as a representation of or extension of herself. Through inserting Willia, Ringgold challenges the dominant narrative in art history where the white female body is hypervisible while the Black body is made to be invisible unless hypersexualized or supporting harmful false stereotypes. These kinds of interventions and investigations about the role and presence of Black Americans in both American and art history are at the center of Ringgold’s first solo exhibition in New England in over fifteen years. Organized by Samantha Cataldo, associate curator of contemporary art at the Worcester Art Museum, the pieces included in “Faith Ringgold: Freedom to Say What I Please” are all centered around Picasso’s Studio, the first piece the viewer sees as they enter the gallery.

The exhibition joins a list of recent shows focusing on Ringgold’s vast career, like her retrospective at the New Museum in New York City in 2022, and “Black is beautiful,” mounted at the Musée Picasso in Paris in 2023. After lending the quilt out to these institutions, Cataldo was inspired to present it on site at the Worcester Art Museum before it returned to storage. Though Picasso’s Studio has been a part of the museum’s permanent collection since its acquisition in 1998, this is the first time in several years that the quilt is on view.

Spanning more than five decades of Ringgold’s career, the fourteen pieces in this exhibition not only showcase the different eras in her career and various media utilized but are also layered in their confrontation of American history and Black existence— particularly as it relates to her personal experience. Ringgold often centers her matrilineage and celebrates the women who came before her, especially in pieces like Faith (1973) and Bessie (1974), both of which are masks part of the Family of Women series, inspired by the Dan masks of Liberia. By comparison, works like the serigraph Woman Looking in a Mirror (2022) examine society’s gaze toward Black women more broadly, repositioning them from a passive subject to an active one.

In Picasso’s Studio, Ringgold explores what freedom means for her. At the top and bottom of the quilt, she inscribed, “You asked me once why I wanted to become an artist and I said I didn’t know. Well I know now. It is because it’s the only way I know of feeling free. My art is my freedom to say what I please. [It’s not important] what color you are, you can do what you want [with your] art. They may not like it, or buy it, or even let you know it; but they can’t stop you from doing it.” For much of her career, Ringgold was excluded from the mainstream art world. It wasn’t until the 1980s, when she began to work on her story quilts, that she started to receive recognition and esteem, decades after her white male counterparts.

Born in Harlem in 1930, the height of the Harlem Renaissance, Ringgold was surrounded by creativity and the renewed struggle for civil rights. At the Worcester Art Museum exhibition, a selection of works from the 1960s and 1970s highlight Ringgold’s loyalty and dedication to civil rights advocacy. The People’s Flag Show (1970), Woman Free Yourself (1971), and United States of Attica (1972) are all political posters displayed as a group on the right side of the gallery. Beneath a map of the United States filled in with descriptions of lesser-known uprisings and acts of violence committed against Indigenous, enslaved, and immigrant individuals, United States of Attica (1972) declares, “This map of American violence is incomplete. Please write in whatever you find lacking.” Ringgold utilized red, green, and black— the colors of the Pan-African Universal Negro Improvement Association—which would later become canonized in art history, particularly through David Hammons’s African American Flag (1990). United States of Attica becomes an interactive piece through the addition of a notebook to the left, asking viewers to engage with the depiction of acts of oppression.

Ringgold’s reexaminations and recontextualizations of history are staples of her career. In Declaration of Freedom and Independence (2009), a series of six acrylic-on-paper paintings displayed on the left wall of the gallery, Ringgold paints well-known scenes like the Boston Massacre and the Boston Tea Party. The paintings seem to be pulled directly from textbooks widely distributed in schools that claim to tell with the utmost veracity the history of the United States. She contrasts these with moments of persecution, subjugation, and resistance of Black Americans, like the lynching of three Black men after the Civil War and the march in Selma in 1965 for voting rights. Through the storybook-style paintings, Ringgold explores the convergence of racial and gender inequality and the difference in the availability of freedom for Black and white Americans. In the series, Ringgold foregrounds how inequality has denied the humanity of Black Americans. These paintings are also an example of how Black history is American history. To try to divorce the two is to invalidate the experiences of Black Americans and an attempt to alter history to fit a narrative that conceals the injustices committed against them.

But in addition to works that spoke more broadly to the history of Black Americans, Ringgold often weaved in stories from her own experiences or those of her ancestors. Installed on the back wall of the gallery is one of Ringgold’s most celebrated and recognizable pieces, the story quilt Tar Beach #2 (1990). Ringgold’s quilts are a reminder of the cultural legacy of quilting in Black American communities. Quilting is an art that was taught to her by her mother and inherited from her great-great-grandmother, who made quilts while enslaved. Tar Beach #2 tells the story of Cassie Louise Lightfoot, Ringgold’s alter ego who flies over the city, represents freedom, and dreams of a future when her parents won’t have to overcome obstacles that generations of Black Americans have had to face. The quilt also depicts domestic pleasures with intimacy and specificity: Cassie and her brother lie on a mattress looking at the stars as the grownups enjoy a rooftop card game. In the background, a table laden with delights alludes to Black American traditions of gathering around food.

For the artist, lying out on tar beaches (the name for the roofs of buildings in big cities) during the summer and spending time with family, friends, and neighbors like Duke Ellington and Langston Hughes, mainstays of the Harlem Renaissance, cultivated her love for storytelling. Not only does Tar Beach #2 display an activity that is distinctly tied to large cities like New York City, but it also shows the vibrancy of the city and how Black Americans have significantly contributed to the construction of the city yet are unable to reap the rewards or relish in simple pleasures like sleeping in or job security.

In the wall text accompanying Declaration of Freedom and Independence, there is a quote from Ringgold that reads “freedom was not more than a promise that would be a struggle and could be, in many instances, denied.” This is a thread that recurs throughout the exhibition, with many of the pieces examining the incessant rejection of freedom for Black Americans. The pieces on display challenge the viewer’s perception and understanding of the country’s history, and as they cover several decades in Ringgold’s career, they are a reminder that this refusal is not solely in the past and continues today. Though her work has been referred to as revisionist, perhaps a better description would be that Ringgold is challenging the way American society and history books have themselves revised the past—and is rectifying it.

“Faith Ringgold: Freedom to Say What I Please” is on view at Worcester Art Museum through March 17, 2024.

This review was originally published in print in Issue 11: Emerge in November 2023.