In a 1970 interview with Artforum, Eva Hesse said, “Art and life are inseparable. If I can name the content [of my work]… it’s the total absurdity of life.”¹ Hesse created objects as a means of understanding herself. At the gallery Hesse Flatow (no relation to the late artist) in Chelsea, NYC, twelve artists embrace the messy, mucky, and murky to comprehend their own experiences in “Getting to Ick.”

The show’s title references Linda Norden’s 1992 essay “Getting to ‘Ick,’”² which was published in the exhibition catalog for “Eva Hesse: A Retrospective” at the Yale University Art Gallery. Norden footnotes her conversation with Sol LeWitt, a close friend of Hesse, who told Norden: “The only word [Hesse] ever used to describe her art to me was ‘ick.’” Norden writes that when asked if he meant “ick” in German (a pun on “Ich,” or “I”) or American (as in the “icky” sense), LeWitt “seemed surprised. ‘American,’ he answered after a pause. ‘Because it’s not pure, it’s not simple, it’s not beautiful.’ But in a later use of the term, he confirmed what must have been its dual resonance for the artist: ‘Her “ick” was getting into herself and her work.’”

Feeling “the ick” is a popular term in Gen-Z media, used to describe severe moments of revulsion, usually spurred by social or romantic moments (or perhaps eggs; see “viral egg ick”). Unlike everyday gross encounters, the ick feels visceral, like a knee-jerk reaction, and personal, specific to one’s self even if shared by others. While abstractions of the body are the focus of the works on display, “Getting to Ick” goes beyond the aesthetics of flesh and moves toward interior depths, revealing textures of perception, memory, and intricate conditions of subjectivity.

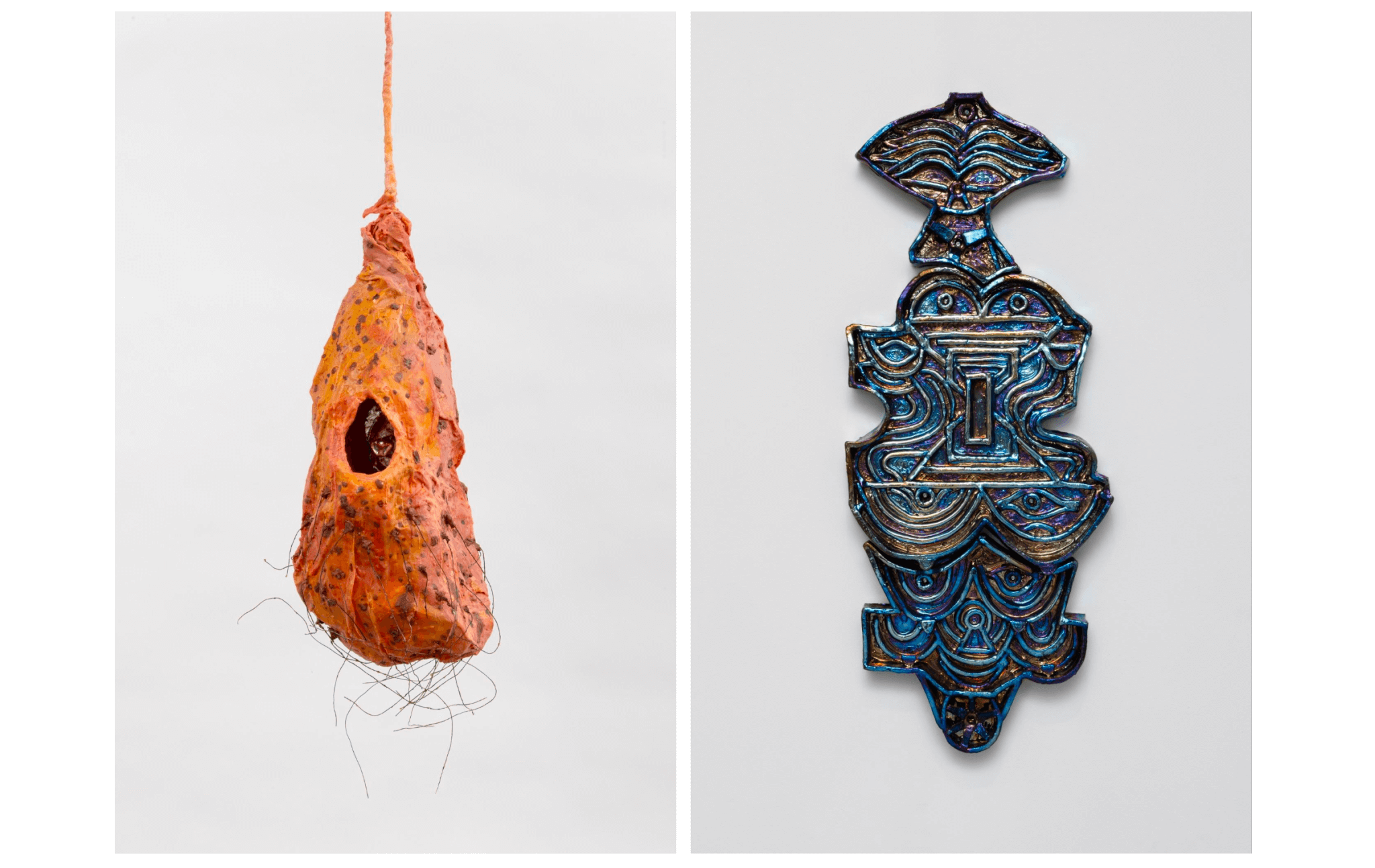

Upon entering the gallery, a sculpture named Envuelta (2020) (Spanish for “wrapped”) by Vermont-based artist Estefania Puerta hangs from the ceiling. Made of beeswax and grapefruit oil, among other materials, Envuelta suggests a cocoon-like beehive. The orangey structure has brown splotches and veins of trickling wax. A deep, dark cavity opens in the middle to reveal a silver snout within. Twiggy branches hang beneath the sculpture. Envuelta transmits the energy of an imagined environment, as if creatures might emerge from inside, or a scent might waft by. Hanging on a wall across the room, Julia Kunin’s ceramic sculpture Carnival Blue (2017) is an iridescent labyrinth that seems to invite an invisible ball to drop through its clever maze. Puerta and Kunin scratch the imagination through enchanted worldbuilding and evocations of presence.

In Molly Lowe’s oil painting Domestic Embrace (2023), swoops of beige limbs, pools of green, orange corners, and bright pops of purple and pink blur into a vaguely domestic scene. Perhaps we see a body sitting in a chair, or maybe everything is a woman’s large face. The longer you look, the more becomes possible; multiple realities coalesce. Bridget Mullen’s Border’s Buckle (2023) also invites multiple vantage points. The painting spins a hideous figure upside down and captures its body from above. The creature’s long reddish and bluish hair touches the ground; eyelashes are long and beautiful. Fingers and organs and noses and knees mix together, making us question where we should look first.

Cambridge-based artist Lucy Kim’s paintings and Grace Sachi Troxell’s sculptures blend in molds and casts of various objects, creating bumpy landscapes of sensual crevices and surprise finds. Kim paints over low-relief casts that hide in plain sight. In Snakes (2020), black snakes slither diagonally across the crinkled surface. Impressions of crabs and seashells jut out or sink into the painting, like traces from sandy mud washed upon the shore. A few noses appear, too; when noticed, the whole painting transforms into a series of faces. The painting isn’t about snakes or faces per se, but the possibilities of subject matter within. In these moments, Kim makes full use of the flexibility of our perceptions. Troxell also creates a fluctuating, fossilized site. Her large sculptural vessel Mamma Pot (2023) sits on the ground. Its surface bulges out into distinct organic forms, like tumors protruding from the body. The material list reads “Clay; casts of my aunt Glady’s stomach, my mother Beth’s stomach, my partner Parijat’s arm, turnip, beet, crookneck squash, acorn squash, carrot, fennel, napa cabbages.” The vessel is open inside, holding a large gas. Marks of robin’s egg blue and yellow trickle down the sides. Mamma Pot is a Frankensteined yet tender carrier of material resonance.

In Leeza Meksin’s Finger Lakes (Closer to the Seen) (2022), a tablet of silver, dark red, roses, bright greens, and deep blues reads like a topographic map or field guide into a mythical landscape. The cratered texture of the paper pulp on canvas makes the object feel like an artifact from Mars. Meksin’s Yes Masked Balls (2023) and Rose was Always Above the Abyss (2022) resemble hieroglyphic how-to manuals, gesturing toward production and industry. Bowls and vases line up, as if sitting on a conveyor belt. In Rose was Always Above the Abyss (2022), human figures and their shadows appear hunched, like they’re standing in an assembly line.

Victoria Roth’s paintings allude to microscopic cells, a seemingly otherworldly yet embodied terrain. In Attachments (2023), dark red, yellow, and blue branches loop and curl around each other, opening a structurally perfect portal into dark blue infinity. In A Little Tighter (2023), a similar set of branches form a cosmic pathway; elongated skeletal fingers standing over a spine of stacked vertebrates. The texture of the painting rises off the panel, emulating hair rising from the neck.

Wood—a material once alive—recurs throughout the exhibition. In Douglas Rieger’s Gross Motor (2023), a pile of large wooden blobs, indented, marked, and pressed upon, sit precariously atop a concrete pedestal. A disconnected baby pink tube runs through the top, rubbing its color around the wooden hole. Ever Baldwin’s extravagantly shaped charred wood frames erect a theatrical stage for their paintings. In Samara (2023), cartoonish eyes or ambiguous furniture parts appear in wobbling symmetry. Boston-based artist Alison Croney Moses’s works seem to enshrine physical sensations. Dark walnut peels back in her Unsewn series (2023), revealing raw material underneath. In Croney Moses’s The Mess of Preeclampsia (2023), blistering bits of compression tights and expanding foam red like blood burst through a skin-like walnut encasing. The artist’s depiction of the pregnancy-related complication that causes dangerous symptoms in almost all major organs is both magnificent and horrifying.

Peaches (2023) and Cocoons (Red and Turquoise) (2023), two paintings by Corydon Cowansage, are the most serene of all. In vibrant color, Cowansage isolates a biomorphic form, replicates it, and organizes a geometric arrangement. The shapes fit together neatly, intimately touching and opening space. In Peaches, four pink lips stack upon each other at different angles; in Cocoons, a pair of reddish tentacles each wrap a tendril against a turquoise background.

The full title of Norden’s essay is “Getting To Ick: To Know What One Is Not.” Hesse rejected feminine aesthetics, eager to establish herself independent of any categories. In the Artforum interview, Hesse says, “I can’t stand gushy movies, pretty pictures and pretty sculptures, decorations on the walls, pretty colors, red, yellow, and blue, nice parallel lines make me sick…” The body holds everything—passions and triggers and ambivalence. “Getting to Ick” excavates the stuff buried under the skin and brings it to the surface. Whether that be grotesque or beautiful, feminine or masculine, the works on display traverse categorical absolutes. Therein lies the ick, an ongoing potential.

1. Cindy Nemser, “An Interview with Eva Hesse,” Artforum, May 1970, https://www.artforum.com/features/an-interview-with-eva-hesse-210575/

2. Linda Norden, “Getting to ‘Ick’: To Know What One Is Not,” in Eva Hesse: A Retrospective, ed. Helen A. Cooper (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

“Getting to Ick” is on view at Hesse Flatow through January 20, 2024.