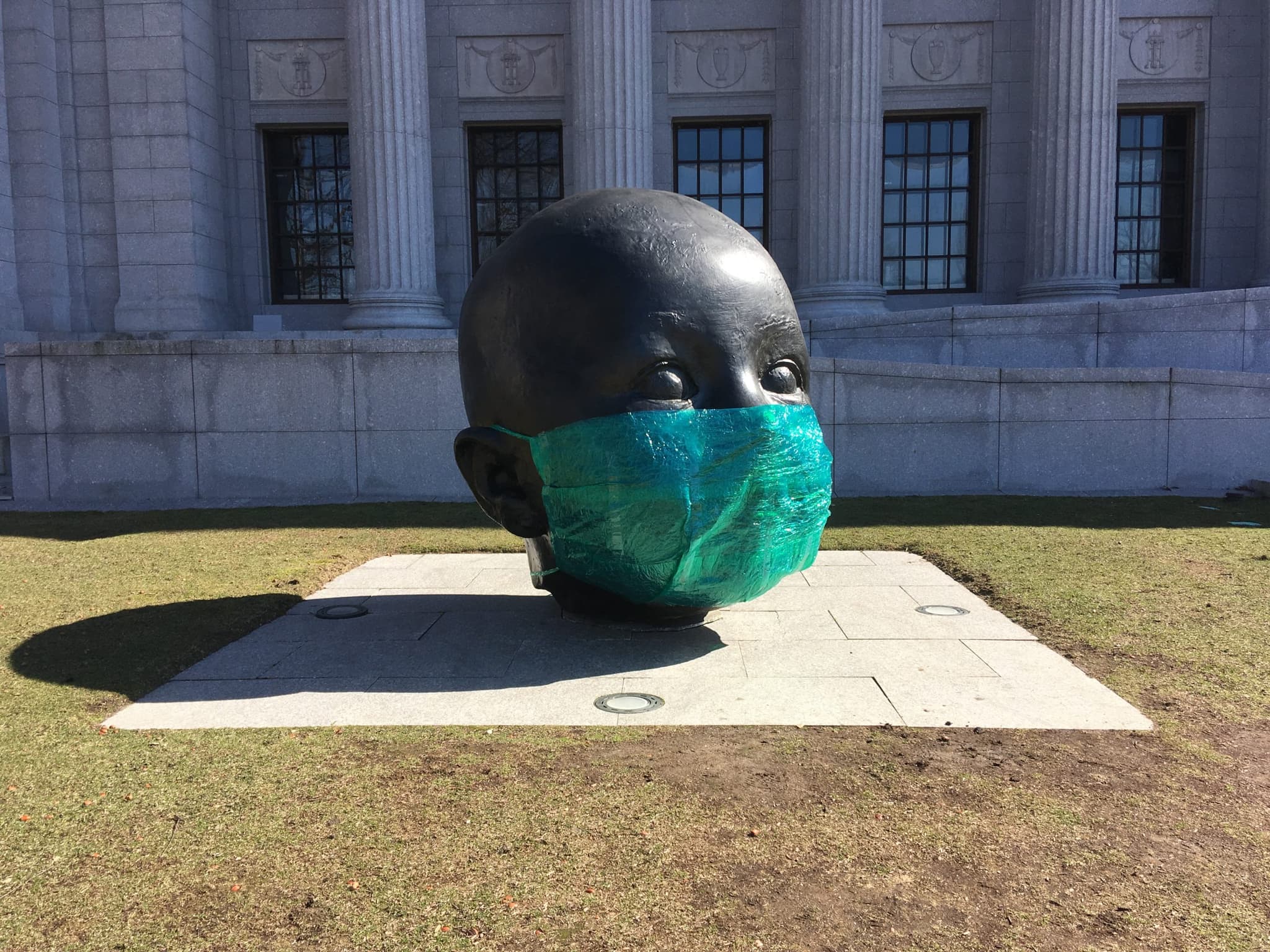

On March 22, 2020, Boston artist and designer Peter Agoos and his nephew Gabriel Fancher staged a guerilla action in the public sphere. Outside the Museum of Fine Arts, where Antonio López García’s eight-foot bronze “baby head” sculptures, “Day and Night” (2008), face the Fenway, Agoos wrapped the nose and mouth of “Day” with colored cling wrap, fabricating a form of personal protective equipment (PPE) for the artwork. Agoos’s ephemeral gesture, simultaneously playful, provocative, and deeply serious, resonated on multiple levels. It operated as a monumental PSA for the social distancing measures and messaging of COVID-19 containment, set within the fraught context of public space. It also played out against the edifice of one of the city’s greatest arts institutions, closed until at least the end of June at press time, with over 300 employees furloughed and an expected revenue loss of up to $14 million. Perhaps most vividly, the work foregrounded the community-sourced and makeshift efforts in mask fabrication that have been a necessary civic response to fill systemic healthcare gaps, and served as a powerful example of the intersection of art and public health. COVID-19 has drawn global attention to the threat of disease. It has also laid bare the many interwoven social determinants of health; from financial stability and healthcare access, to early childhood education and social connectedness and support. According to Dr. Shan Mohammed, board-certified family medicine physician and professor of health sciences at Northeastern University’s Center for Health, Policy and Law and the Global Resilience Institute, disruption of any of these key determinants can have negative health impacts. But with the novel coronavirus pandemic, he says, “All at once we’re disrupting so many social and structural determinants of health and well-being.” The key determinant of social connectedness has been directly compromised by the very means through which we “flatten the curve”: If stay-at-home orders and physical distancing in public limit our ability to meaningfully connect with others, then they may also engender or exacerbate ill health. As Julianne Holt-Lunstad’s landmark 2010 study revealed, poor social support is a major contributor to morbidity and can pose a greater health risk than smoking, obesity, and substance abuse (1). Prolonged social isolation can lead to chronic loneliness, resulting in an increased risk for a multitude of health problems, including stress and trauma disorders, depression and anxiety, dementia, cardiovascular disease, and even impaired immunity (2). We are also likely to see an uptick in behavioral threats to health, including substance abuse, domestic violence, and child abuse, and people struggling with addiction or trapped with their abusers are severely limited in their ability to draw on the social support networks that are key to their survival. These negative health impacts are a possibility, but they are not an inevitability, and Dr. Mohammed is curious: “What role can the arts play, from helping individuals stay healthy to helping communities recover, regarding the challenges presented by COVID-19?” Decades of empirical research connecting art, healing, and public health suggests that participation in the arts can help to reduce adverse physiological and psychological outcomes. As the new CultureRx initiative from the Massachusetts Cultural Council illustrates, music, dance, theatre, visual arts, and expressive writing might all be leveraged as powerful public health interventions. While the extant research could benefit from more longitudinal studies bringing together clinical experts, biostaticians, and those with artistic expertise, there is general agreement in the public health research community that the arts can shape how we think about health and support our personal and collective wellbeing (3). More importantly, arts participation can serve as a powerful intervention on individual and collective feelings of insecurity, disunity, and apathy that are exacerbated by social isolation.

Issue 05 • May 21, 2020

Artists Are Essential Workers

In the midst of COVID-19, Amy Halliday and Rebekah E. Moore evaluate the role that arts and culture plays in public health.

Critical Perspective by Amy Halliday

Peter Agoos, PPE for Antonio López García's "DAY," 2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

Peter Agoos, PPE for Antonio López García's "DAY," 2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

Ally Schmaling, Queerentine portraiture series, 2020, courtesy of the artist. “I asked them all one question: What tiny moments of joy have you found in all of this?” Shana (she/her) & Stacy (she/her), Leah (she/her) & Jahna (she/her) “Almost every night at 6, we meet for porch time with our neighbors. They’re on the 3rd floor, we’re on the 2nd. Sometimes it’s sad, sometimes it’s silly – it’s a way to check in on each other, but, you know, it draws out the whole neighborhood too. It’s like this visible moment of humanity on display.”

The World Health Organization recognizes health as a complex and context-specific “state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being rather than merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” For member nations of the WHO, “the extension to all peoples of the benefits of medical, psychological and related knowledge is essential to the fullest attainment of health” (italics ours). The work and impact of the visual and performing arts might be envisioned as part of the essential “related knowledge” at stake. But how can those healing modalities be leveraged when arts institutions are shuttered, concerts and theatre productions are cancelled, and many artists are left without the resources necessary to assemble an antidote? According to the Americans for the Arts’ ongoing survey response to COVID-19, the economic impact on the arts and culture sector reached more than $4.8 billion in financial losses and unexpected expenses by the end of April. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts was second only to New York for the greatest financial impact (4). According to Mass Cultural Council’s March 24th report, the cultural sector had already reached more than $55 million in lost revenue in the early weeks of the shutdown, and more than 8,200 jobs: 70% of these were held by artists (5). How might artists responsibly attend to both public health crises—COVID-19 and social isolation—while also facing major disruptions to their financial stability and limitations on reaching audiences, and one another? Dance artist and Bridgewater State University faculty member Kristy Kuhn, who was forced to carry her studio instruction to the digital sphere in early March, says, “The arts already struggle with financial support in many ways, and my biggest fear is the ability to bounce back quickly and continue thriving.” She also fears that many of her students may be unable to return to their dance studies after campuses reopen. Creative Responses In order to address these particular and interrelated concerns, we brought together the voices of Boston-based clinicians, artists, and cultural workers to consider: How are creators thinking beyond the confines of gallery walls and concert halls to envision new means of building aesthetic, emotional, and social connection where physical connection is denied? How might we respond to this specific moment—and beyond—by reimagining art as fully inclusive and participatory, and as an essential human service? And in what ways might we prepare to advocate for artists to gain and maintain the resources they need to continue to support our individual and collective resilience?

OJ Slaughter, (left) Dana Brooks in Newburyport, MA on 3.14 at 3:28, FaceTime screenshot, 2020, (right) Kris Nevaeh in Mattapan, MA on 3.14 at 3:42, Facetime screenshot, 2020. Images courtesy of the artist.

Lauren Pellerano Gomez, senior director of communications at Boston Center for the Arts (and previously of teen creative program Artists For Humanity), says they have been drawn to photographic responses to COVID-19, considering that questions of distance and intimacy between a photographer and their subject have always attended the medium’s history (6). Photographer OJ Slaughter, who is known for their strong graphic work as visual creative director of WBUR’s “Sound On” series celebrating local musicians, has been finding new ways of visualizing identity, connection, intimacy, and community across social distancing divides, while also playing with notions of interrelational, mediated authorship. Through video-messaged conversations with close friends about how they are coping in this crisis, Slaughter helps them build the setting for their portraits, before taking screenshots that capture the “essence” of the exchange—a certain slant of light through a window, a moment in meditation or lost in music, or sequester in the Arnold Arboretum—complete with the textural graininess of unpredictable digital interpolation and signal strength across the distance that separates them. For Pellerano Gomez, one of the brightest moments during quarantine was being photographed with their partner outside of their home in Jamaica Plain—from ten feet away—by Ally Schmaling, as part of Schmaling’s “Queerantine” portraiture series. The experience was deeply meaningful, explains Pellerano Gomez, “because I was able to see someone who takes up heart space for me creating work in real time… Ally’s project speaks to the universality of the human experience during a traumatic event: the isolation experienced and the critical importance of interconnection and community.” Schmaling’s project is a documentary effort to trace this moment, but also to specifically visualize and celebrate “queer personhood, chosen family, and community resiliency.” The images are shared digitally on Instagram, but the underlying process remains fundamentally analogue, embodied, and interrelational: It builds from, expands, and reinforces the social networks that weave the safety net of queer community/ies in Boston. Participants’ comments integrally accompany the images, and present an archive of localized knowledge, self-reflection, and practices developed for personal and household wellbeing—all social determinants of physiological and psychological resilience in the face of adversity.

Ally Schmaling, Queerentine portraiture series, 2020. Pictured: Shan (they/them) & Lauren (they/them) “Befriending squirrels. We talk a lot to squirrels lately.”

Ally Schmaling, Queerentine portraiture series, 2020. Pictured: Anjimile (they/them) & Rae (she/her) “I keep meditating on the whole idea that indigenous communities and farmers for centuries have intentionally burned fields to plant new seeds. Like, some seeds only germinate if they’ve been scarred by fire. And I keep using that metaphor – maybe this is the fire. And now we can finally start planting these new seeds of better structures that serve us all.”

David Guerra, founder of AREA Gallery, believes that the arts are critical in our search to understand and process experience, especially in a saturated media environment. Guerra had just mounted an exhibition of paintings by Cal Rice—aptly, if coincidentally titled Cancel Your Plans—before having to close his physical space. Newly contextualized by the pandemic, Rice’s paintings speak to a broader sense of existential unmooring, in which institutional, political, and social structures have failed many, leading to a widespread sense of alienation. His uncanny renderings of human disconnection, set within the relative (and by no means assumed) “safety” of home (Entropy), or the sense of foreboding that attends a crowded bar scene (Last Call), powerfully capture something of the strangeness of now, of our inability to fully comprehend another’s interiority.

Cal Rice, Entropy, gouache and acrylic paint on wood panel, 2019. Image courtesy of the artist and AREA Gallery.

Recognizing the importance of connection, of forging ways of “being with” each other and with art, Rice’s gallerist has shifted his focus from the traditional model of individual representation toward building community among the gallery’s artists. Every Friday, Guerra hosts a virtual gathering, where the emerging artists he champions check in with each other and take turns hosting studio visits. Through this, artists have become each other’s support network and viewership. Privileging process, collaboration, and reflection over outcomes, they are conceiving of “space” anew. New media installation artist and opera director Laine Rettmer, for example, has been workshopping Play it Safe, a video piece inspired by classic movie screenings in Italian towns. It is at once a fun diversionary tactic for enjoyment from a safe distance and a pointed critique of the homogenous representations of women we are likely imbibing in our increased media intake. Throughout May, the work will be projected onto the outside of the homes of AREA artists based in neighborhoods across Boston, Cambridge, and Somerville, connecting a network of creatives with their communities in turn. Rettmer has also been experimenting with watercolors, making fluid portraits during video conversations and assembling them into her digital artistic community.

Laine Rettmer, installation view of Play it Safe, live projection on a Somerville artist’s home, part of an urban art intervention series produced and curated by Pamela Hersch with David Guerra.

Laine Rettmer, Circuit Portraits, watercolor, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

Jerry Beck, visionary artist and executive director of ArtSpace Maynard, and Coraly Rivera, Puerto-Rican born high school teacher and artistic director of the Revolving Museum, have created a mobile convoy of crowd-sourced artistic installations on wheels: “Corona/Crown Art Project” consists of a transformed 1952 Ford pickup truck pulling a trailer covered in brief English and Spanish poems encouraging adherence to public health advice. A second vehicle tows a ten-foot sculpture of a masked head wearing a jeweled crown intended to honor frontline workers in healthcare, agriculture, supply chains, and sanitation work. The work is community-“powered” by the results of an open call to contribute poems and “cure-cell” artwork to the convoy. Photographed, printed on waterproof paper, and adhered to the convoy, the “cure cells” are round artworks representing anti-viruses as seen through a microscope, and drawing on individual visions as well as diverse cultural traditions. Earlier this month (May), the convoy began its travels through greater Boston, Essex, and Worcester counties, making a loop around the State House for good measure at the outset. Back and Rivera invite viewers to enjoy it from a safe physical distance, delivering the work to new “publics” assembled in grocery lines or out on neighborhood walks with household members. Peter DiMuro was working on a new project when the U.S. coronavirus outbreak was just surfacing: “Stones to Rainbows: Gay to Queer Lives” was intended as a story-gathering project that would translate queer narratives into art installations and pop-up live cabaret performances throughout the city. The project has now pivoted to an online archive of queer stories that will inform a dance response, signified by the title of his April 24th virtual talk for the Black Brown Queer Dance collective at Tufts: Viral Intimacy: Intergenerational Queer Artmaking. “Stones to Rainbows” is a reflection of DiMuro’s modus operandi in his four decades of work as a dancer and choreographer, which he likens to the role of a storyteller: “That’s basically what we’re doing, whether it’s dance or music…we’re creating mini portraits of people and their relationship to others.” DiMuro recognizes many similarities between his current work in this moment—what he describes as a process of “illumination, not illustration”—and his creative and activist work during the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis.

Jerry Beck and Coraly Rivera, Corona/Crown project, 2020, mixed media mobile installation. Image courtesy of the artists.

Artists as bridge-builders This moment seems to require that we prioritize connection and community over singular creative genius: to recognize that we cannot go back to “normal,” because “normal”—in the arts world and our wider social macrocosm—is rigged to only ever recognize and benefit a select few. “If we’re so concerned about making art for other artists, then we miss out on the opportunity to include this vast array of people in our world,” explains DiMuro. “We’ll miss this kind of in-between place, where we’re actually evolving people’s feelings, emotions, and the detritus of all this into a workable daily practice of movement, of humming the song, of writing down the story.” Great works aren’t what matter now, by DiMuro’s estimation. The great anthems and monumental responses offer only temporary relief from the symptoms of creative and social disruption we now endure. What is needed is participatory art: Art that enables interaction, amplifies every voice, and provides a sense of personal and collective accomplishment, belonging, and hope. Dr. Mohammed concurs, when it comes to potential artistic interventions in public health: “Countering social isolation is about active engagement and connection. This idea of skill development; learning, creating, sharing and getting active feedback.” Many artists and arts organizations have long understood the centrality of active arts participation in cultivating resilience. Organizations like East Boston’s ZUMIX even shrug off the designation of arts organization entirely, in order to center their work on youth and community development. Through a range of music education programs, including music and dance lessons, audio production and songwriting courses, and their own in-house radio station, ZUMIX is invested in the power of music to support individual and collective thriving. Since closing the Firehouse, their beloved community center in early March, ZUMIX has sought new modes of creative and community connection: They launched the campaign, “Sing a Song, Send a Song,” inviting everyone (no great musicianship required!) to share and dedicate a song to someone they are missing during this pandemic. COVID-19 has brought on so many economic, educational, and healthcare hardships; it has also become an opportunity for close scrutiny of what happens to communities when they lack public space in which they feel represented and safe. Yet as dance artist Kristy Kuhn asserts, “People are learning to connect in new ways.” She envisions artists prioritizing their role as community bridge-builders, “bringing people together at a time when it is most needed, and with a common goal to help uplift humanity, to give communities voice, to create together, to feel like we’re a part of something bigger and positive…the arts have an unbelievable way of allowing us to do that, especially in these challenging times.” DiMuro muses on the timeless role of artists as storytellers of the now: “What about this life now? What are the stories we need to be gathering now, and who are the essential workers—you, me, and other artists who can take the stories and journey them…to heighten, to celebrate, to illuminate these stories right now, while they’re fresh and they’re so emotive, so that we can help people walk that journey, emotionally and physically?” From the public health realm, Mohammed also imagines an expanding role for artists: “I think what needs to get out there is the role that the arts play in the well-being of individuals, families, and society…What are the tools of established art therapies—music therapy, art therapy, poetry, etc.—and how can those be expanded to serve everyone—healthcare providers, those with preexisting conditions, and those who are facing complete disruption to their lives, feeling unsettled, and feeling stressed with this physical distancing? And then how can arts be used for advocacy? How can the arts be used to bring voices to those who are most vulnerable, to advocate for greater justice?” Visionary leadership As we urgently engage with the current crisis, we also need to consider what is ignored or exacerbated in its wake. Kara Elliott-Ortega, chief of arts and culture for the City of Boston, echoes this sentiment: “When our worlds are turned upside down, and our ways of processing and relating are yanked out from under us, we see how significant shared cultural experiences are to bringing definition to our lives, helping us process trauma and pain, and bringing us joy. Joy is not just a matter of nice-to-have self-care. In a time when we see even more clearly how stress and negative health outcomes are inextricably linked to racism—this is a matter of equity and well-being.” Elliott-Ortega continues, “There are also questions about the future we want moving forward. We’ve seen some amazing actions take place in the context of crisis—rent relief, sheltering the homeless, increased food access. How can artists help us imagine a future where those policies become status quo? Where the crises of racism and poverty are treated with the same urgency and swift response as COVID-19? We need that radical imagination now, and artists are already providing it.” Certainly, many contemporary artists have long engaged in the nuanced critique of systemic injustice, and with fomenting structures for community organizing and collective action. Simone Leigh, for example, has directly taken on the failures of the U.S. health system, particularly in relation to the experience and treatment of black women, in “Free People’s Medical Clinic” (2014) and “The Waiting Room” (2016). Both works include facets of a holistic alternative vision spanning community-based knowledge and shared creative practices of self- and communal care. But in order to actualize “the future we want moving forward,” artists must be envisioned as playing a multitude of essential roles within society, including within healthcare. They need to be leaders and participants in every sector, part of a civic reimagining and activation of what we value. As Randi Hopkins, director of visual arts at Boston Center for the Arts, points out, FDR’s federal New Deal invested deeply in culture as an integral component of democratic citizenship and public wellbeing in alleviating the socio-economic effects of the Great Depression. Under the many arms of the Works Progress (later Projects) Administration (WPA), progressive infrastructure encompassed not only the building of schools and roads, community art centers, sanitation systems, and botanical gardens: it also meant collecting stories (think the work of folklorist, anthropologist and novelist Zora Neale Hurston), developing a nationwide theatre program, devising an ambitious visual arts agenda (most famously in mural painting, fostering some of the most famous artists, and artistic networks, of the postwar era), and delivering an estimated 5,000 live music performances to some three million people a week, along with a massive expansion in community arts instruction. UK-based curator Hans Ulrich-Obrist recently made headlines calling for a new WPA for artists (7), but while he draws on a US precedent, it seems hard to imagine federal-level support in the current political climate. Perhaps Boston could lead the way, muses Hopkins: “Under strong, visionary leadership, there could be some really interesting possibilities.” Elliott-Ortega suggests that Boston is well on its way to envisioning a leadership role for artists: “As an office, we spend more than half of our budget on funding, support, and programs for individual artists. This is unusual for a city arts office, but it comes from the understanding that artists and creative workers are the power source—they’re creating, they’re connected to their communities, and they’re farther ahead than the rest of us (government and arts non-profits included).” Because of artists’ critical acuity, creativity, and responsiveness to what’s going on around them, says Elliott-Ortega, they’re among the most innovative people in the city. Recognizing this prompted City Hall to start its own artist-in-residence program: “…We believe that when you get artists and government bureaucracy close together, there are amazing moments of productive tension—opportunities to test new ways of doing things and support artists and city workers in the process.” None of this essential work can continue if artists have no means of livelihood—if they lose access to both studio space and home and must move to other cities or other occupations in order to survive. David Guerra feels that Boston still has a long way to go: “One thing I’ve been an advocate for is investment in the arts that is not just about giving grants, but [affordable] places to live and work…and for cultural organizations to be seen as co-investors in civic life, rather than as ‘tenants.’” Dr. Sandro Galea, dean and Robert A. Knox Professor at Boston University School of Public Health and one of the leading clinical voices on Boston’s COVID-19 response, wrote about the valuable intersection of art and population health in his commentary on BU’s 2018 symposium, “Humanities Approaches to the Opioid Crisis.” His words resonate with new relevance today: “We must widen our gaze, and see the crisis through the lens of many disciplines, including art, if we are to stop it. (8)” The arts empower us to make meaning, forge connections, and build resilient communities; critically reflect on our own behavior and collective experience of trauma; and empathize with others facing their own challenges. The arts can also help us imagine—and thus activate—our way to better futures. This is our opportunity to transform the way we advocate for artists and arts institutions; for we are not just advocating for the livelihoods of the individuals involved in creative work, but for the collective wellbeing of us all.

1. Holt-Lunstad, Julianne, Timothy B. Smith, and J. Bradley Layton, “Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic Review,” PLUS Medicine 7, no. 7 (2010). 2. Hawkley, Louise C. and John P. Capitanio, “Perceived Social Isolation, Evolutionary Fitness, and Health Outcomes: A Lifespan Approach,” “Philosophical Transactions, The Royal Society Publishing B 370 (2015). 3. As argued in Stuckey, Heather and Jeremy Nobel, “The Connection between Art, Healing, and Public Health,” “American Journal of Public Health” 100, no. 2 (2010): 254-263. 4. “The Economic Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) on the Arts and Culture Sector,” Americans for the Arts, 2020. 5. “Economic Impacts of COVID-19 on Massachusetts’ Cultural Sector,” Mass Cultural Council, March, 2020. 6. Pellerano Gomez was also editorial director at Boston Art Review from 2017-2018. 7. Lanre Bakare, “UK gallery curator calls for public art project in response to Covid-19”, “The Guardian,” March 30, 2020. 8. “How Art Reflects the Conditions that Create Health,” Boston University School of Public Health, October 19, 2018.