Curated by Pilar Tompkins Rivas and originally organized for the Vincent Price Art Museum in Los Angeles, “A Decolonial Atlas: Strategies in Contemporary Art of the Americas” has come to Tufts’ Tisch Family Gallery to challenge notions of regionalism and imperialism in Latin American art. From January 16 to April 15, the small gallery undertakes an open exhibit broken into loose sections by angular dividers. The exhibit features works of collage, photography, sculpture, painting, and video, created by artists from Latin America and the USA. Each piece was carefully selected by Tompkins Rivas to question the ways in which Eurocentric worldviews have created hegemonic structures: monopolizing power, dictating ideological narratives, and othering non-Westerners since the European colonization of Latin America and the USA.

Online• Apr 26, 2018

Beyond Regionalism: A Decolonial Atlas at Tufts University Art Gallery

Review by Lizi Ham

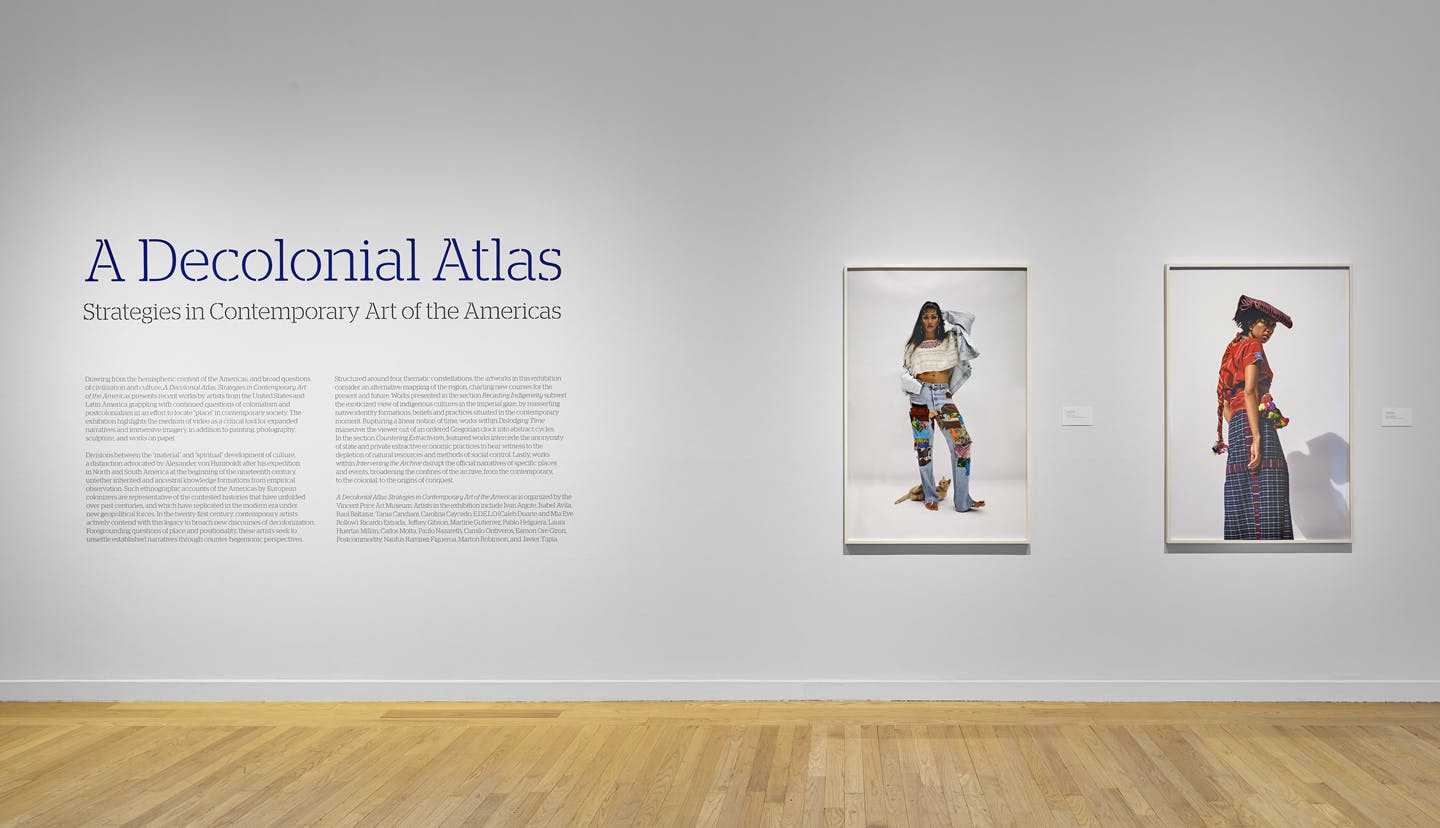

Installation View, "A Decolonial Atlas: Strategies in Contemporary Art of the Americas" (2018). Image courtesy of Tufts University Art Galleries.

Installation View, "A Decolonial Atlas: Strategies in Contemporary Art of the Americas" (2018). Image courtesy of Tufts University Art Galleries.

Carolina Caycedo, Spaniards Named her Magdalena but Natives call her Yuma, (2013). Still. Courtesy of the Artist.

In Carolina Caycedo’s Spaniards Named Her Magdalena, But Natives Call Her Yuma (2013), the English-Columbian artist presents a diptych-style video installation of the main river that runs through Columbia, the Yuma. In one screen, the artist presents footage of the Yuma and the El Quimbo dam. On the right, she shows people from the region. In crowds, slowly moving as a mass, their bodies fill the entire screen. Yet at times, fishermen, families, and community members are shown interacting with the river as a lifeblood on an individual, even intimate level. The artist conducted a series of interviews with artist, architects, researchers, and community members who are being directly affected by the development of the El Quimbo dam; a project that is being conducted by a transnational corporation. In an interview with Pilar Tompkins Rivas, Caycedo shared that, “Six towns in the local county subdivision of Huila are directly affected by El Quimbo, and approximately 3000 people will be displaced through its construction.” The contrast presented between the two screens illuminates the relationship between people from the region, while also highlighting the potential damage unaffected multinational corporations have the potential to wreak on a community.

Many pieces in the exhibition present a challenge the assumption that to be “indigenous” means to be from an era, place, or idea of the past. Three portraits by photographer Isabel Avila greet viewers upon entering the gallery. These photographs direct the viewer to consider that the Pawnee Indians succeed in existing in contemporary urban settings while still maintaining their cultural identity, beliefs, and practices. Martine Gutiérrez’s photographs on the opposite wall provoke similar dialogues. This section of the gallery is part of ‘Recasting Indigeneity,’ the first of four ‘thematic constellations’ the exhibition is divided into, each fostering a different theme. ‘Recasting Indigeneity’ interrupts the Occidental gaze by reframing narratives about indigenous peoples through contemporary contexts and pop cultural references such as basketball courts and hoop earrings.

Tania Candiani, Tiempo Circular, (2013) video. Courtesy of Tufts University Art Galleries.

The second thematic constellation ‘Dislodging Time’ refers to the acknowledgement of diverse classifications of time occurring simultaneously. This includes the Western linear interpretation and the pre-Columbian cycles, which combines history and geography to give a sense of place and the changes that occur there rather than numbers. Theorist Néstor García Canclini coined this notion of abstract time as “multi-temporal heterogeneity.” An example of this lies in the way Naufus Ramirez-Figueroa informs viewers of this concept in his large-scale projected video A Brief History of Architecture in Guatemala (2010) in which three performers collide in bulky costumes which are removed over time to expose raw humanity, stripped of its previous clothing and comforts.

Marton Robinson, Money Talk, (2012-2015). Costa Rican currency with screen print. Courtesty of Tufts University Art Galleries.

The third thematic constellation ‘Countering Extractivism’ criticizes the depletion of natural resources as a result of the extractive economic practices of European colonization. Pieces within this section illuminate issues with transnational corporation and intergovernmental involvement in exploitive water, land, and labor practices. Here, Caycedo’s video installation is accompanied by Marton Robinson’s Money Talk (2012-2015) in which he inserts Black People onto the Costa Rican currency, a narrative, which he states, is often excluded and their very existence is denied.

The final thematic constellation ‘Intervening the Archive’ aims to invalidate the accepted historical accounts created by European conquerors in order to disrupt the existing power structure and compel viewers to deeply consider that there is more to what has been accepted as ‘history.’ As a collection of work, hegemonic narratives are disrupted, presenting a re-evaluated, or contemporary inquiry of the legacy of colonialism, conquest, and expansion.

Installation View, “A Decolonial Atlas: Strategies in Contemporary Art of the Americas” (2018). Image courtesy of Tufts University Art Galleries.

The gallery space is not organized with a specific route in mind, so the sections may be viewed in any order. This means the thoughts of one section flow seamlessly into the next and thus further support the idea of the artists corroborating one others’ messages. Each thematic constellation gives context to the next by using nonlinear cycles of time. In short, through their personal contemporary perspectives, the curator and artists each individually seek to challenge the accepted concepts of cultural history ownership, hegemony, time, and indigeneity. By partnering together, these messages are given the opportunity to enhance and support one other, resulting in a successful disruption of the accepted beliefs resulting from colonization.