This content is available in print in Issue 01 of Boston Art Review Magazine. You can order your copy here. Enjoy this sneak peek!

If you have visited the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston’s Art in the Age of the Internet: 1989 to Today, you would be remiss to have missed Judith Barry’s Imagination, Dead Imagine (1991). The installation is situated as the centerpiece within the “Hybrid Bodies” section of the exhibition. Showing five perspectives of an androgynous, human head on five respective sides of a cube (the top of the cube unavailable for direct viewing). Unidentifiable, thick, oozing liquids cover the head, then are wiped clean, leaving the head prepared for yet another cycle of subjugation. At 10 feet high, viewers are faced with an uncanny depiction of what could, or already might be, our abject reality. Yet beyond the contemporary and future implications of this piece, Imagination, Dead Imagine exists within a critical canon of uniquely disruptive, feminist art practice.

Barry’s work and career is nearly impossible to pin down to a single medium, discipline, or practice. Whether through writing, film, installation, or immersion, Barry utilizes a research-based methodology that places the viewer in direct conversation with the piece, thus providing subjectivity and multiplicity to the viewing experience. At a MIT Catalyst Conversation in March of 2018, Barry joked with the audience about the versatility of her work, stating that people are often “surprised” to learn a certain piece was created by her. As the audience laughed and nodded, I was struck by the validity and power of that comment.

Barry currently has two pieces on view in Boston: Imagination, Dead Imagine at the ICA and untitled: (Global Displacement: nearly 1 in 100 people worldwide are displaced from their homes) (2018). Frequently traveling between New York City and Cambridge, Barry and I planned to meet at her MIT office, but were stopped by a late season blizzard. We corresponded via phone and email, exchanging thoughts and images about the two pieces currently on view while addressing the great expanses in between.

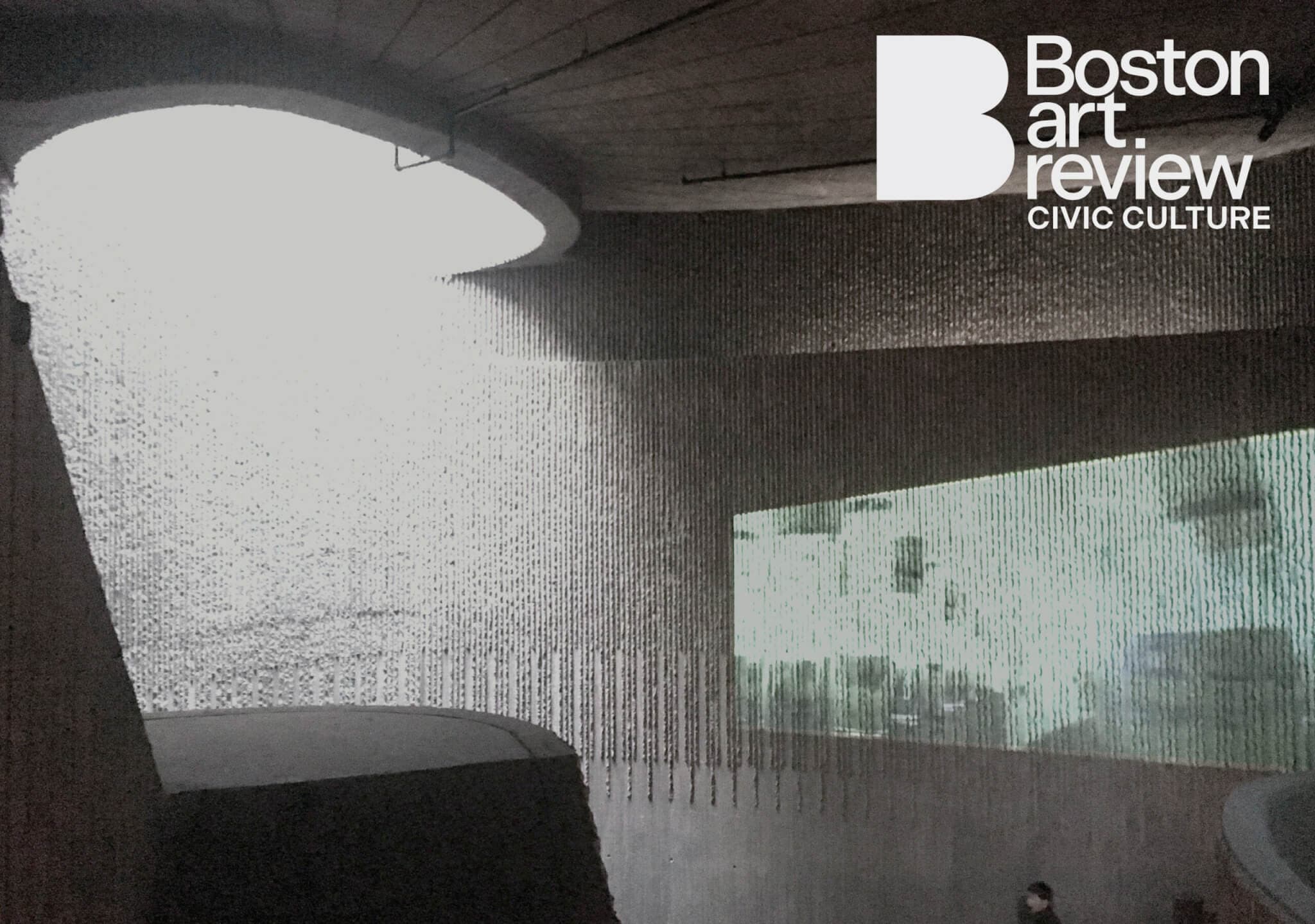

pastpresentfuturetense…ppft, 1977. Performance still: sand curtain as it releases from the ceiling. Photo courtesy of the artist and Mary Boone Gallery.

You’ve mentioned before that you don’t possess a “signature style” and that this allows you to conduct further research and exploration as you create. Can you tell us more about your process and the relationship between research and your work?

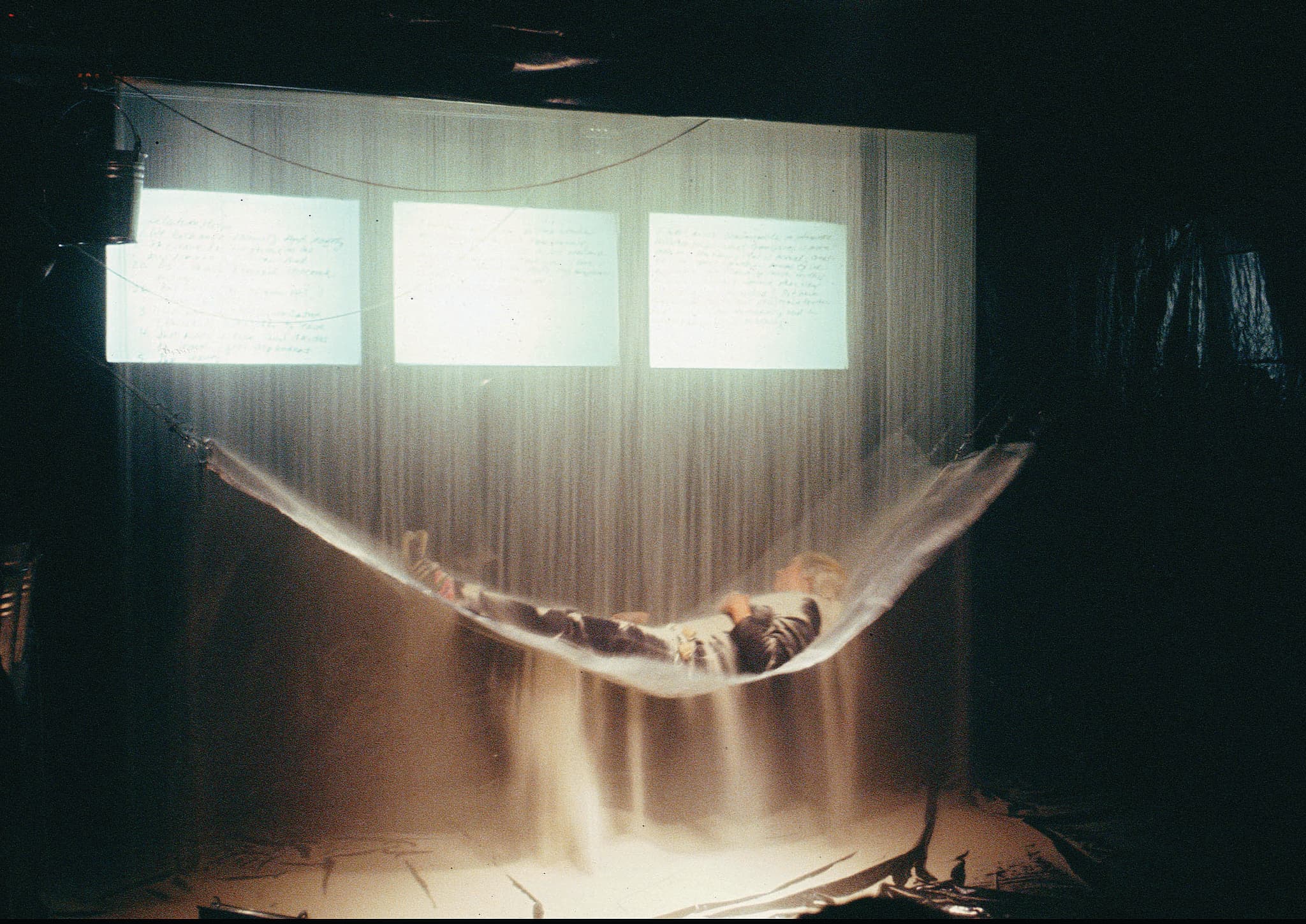

I have an eclectic background coming out of dance, performance, and architecture, simultaneously. Then at UC Berkeley, in the late 1970s to early 1980s, multiple disciplines converged within the Rhetoric and Comparative Literature departments: film and film theory, cultural studies, feminisms, semiotics, post-structuralism, literary theory, and cultural anthropology. Meanwhile, the dominant art discourse was pluralism. It was a great time to be studying at UC Berkeley and SFAI. San Francisco was a big art center in those days and included many artists who were in the 1972 Documenta as well as many dance and theater companies. When I began ‘emerging’ as an artist, I called PastPresentfutureTense (1977) a ‘performance installation’ because I left all the media running for a few days after the performance ended. I was still using the body, as many other performers had done—Joan Jonas and Vito Acconci—by then Yvonne Rainer was already making films….but as everything that could be done to the naked body had already been done, I needed to find something else to do. I wanted to find a form that would allow me to combine all of my interests as I was developing the work, hence why being identified with a specific medium was too rigid. In architecture, we consider that we have a practice and I began using that term to describe what I did. What I was actually doing was continuing the tradition of installation-making, which has a very long history.

When you began to perform, your work dealt directly with the body, yet utilized media and technology. What prompted you to investigate those mediums?

I was interested in how the body was being transformed by the discourse I was exploring at UC Berkeley. Already in my performances I was using technology. PastPresentfutureTense, for example, used three slide projectors and a dissolve unit plus a complex two-channel soundtrack. At the same time, the computer became a tool for video editing. I was freelancing as a party designer in San Francisco—see Coca Cola on my website. Then, in 1981, my video Casual Shopper became popular and by 1984 I decided to move to NYC. At that time, video in museums and alternative spaces was displayed on monitors in non-spaces: hallways, basements, bathrooms, near cafeterias. It was impossible to have a cinematic experience within those viewing conditions.

And video was not part of the dominant art discourses—despite great curators like Barbara London at MoMA and John Hanhardt at the Whitney—and writers such as Maggie Morse, Jim Hoberman and many, many others. I began proposing film/slide installations to curators in NYC as I wanted my work to function spatially, the way large painting did at that time.

Finally in 1985, Valerie Smith at Artists Space exhibited In the shadow of the city… vamp r y (1982-1985), a 20’ x 10’ double-sided slowly dissolving slide projection with film-loops running in the windows on either side of the screen. You could see the entire work in a minute by walking around it. Or, you could spend a longer amount of time if you wished. The installation worked on the viewer by using narrative syntagmas and a cinematic soundtrack that encouraged viewers to parse the narrative together as they circled the work. In 1986, Echo, which has a similar structure but different content, was commissioned for the newly renovated MoMA.

Casual Shopper, 1980-81. Video stills. Single channel color/stereo video. 3 versions: 3 minute, 6 minute, 28 minute. Photos courtesy of the artist and Mary Boone Gallery.

How have you seen the intersection of performance, tech, and body/identity politics develop?

The 1980s introduced tools of analysis into the art world by applying some of the discourse I mentioned previously to specific cultural investigations across a wide variety of topics. The aim was to show how both the form and the content of an inquiry carry meaning, and how there is nothing outside of ideology—very broadly defined as the social fabric. These tools produced meta discourses which allow for a much closer reading than the humanist tradition does; think master narratives, which they supplanted. All during the 1980s and early 1990s, questions about the body—in particular, the woman’s body and slightly later ‘other’ bodies: African-American, Latino, Queer—were debated.

How could these implied ‘differences’ be recognized and what forms of juridical support needed to be in place to do so? We are still grappling with all of these questions. These debates paved the way for gender studies, queer theory, and identity politics. Recent political upheavals have only made the unanswered questions they each have raised, in different ways, even more pressing—not less. To mention just one example: how do different definitions of the terms that define these discourses affect the discussions? How do we acknowledge the fact that it is the differences in our understanding of these terms that are at stake here. For instance, the #metoo movement and the variety of approaches to the question of harassment.

We’ve certainly seen significant change not only in the language, but also in the art making strategies surrounding these topics since the 1980’s. How have you seen these tools for analysis come in and out of play?

For reasons that elude me, the use of discourse as a tool for close analysis has not continued into our present moment as strongly as I would wish. I thought these tools would be further developed by now and that newer forms and terms for meta-critiques would have emerged. I am speaking about the performance of close and careful analyses across a wide variety of social issues, where such terms and an understanding of their implications would inform and connect across disciplines in productive ways; in ways that might aid in untangling the many contradictions at work within our present condition.

In 1980, as an emerging artist, I wrote “Textual Strategies: The Politics of Art-Making” with the film historian Sandy Flitterman-Lewis. Our argument took the notion of ‘the body as destiny’ to task by using psychoanalysis and art history alongside semiotics to clarify the underlying strategies of four different types of artwork produced by women. In many ways it was my version of a manifesto.

The cinematic apparatus as it was defined then–it was not only film, but also the institutions that produced it and the audiences who consumed it–was seen as intimately engaged with questions of the body and of technology. The premise was that the psychic apparatuses invoked when a viewer engages with a film produce an identificatory relationship with the film and this relationship takes you [the viewer] somewhere. All of the technologically-derived forms of visual pleasure do this—television, chatrooms, Facebook, video games, VR, AR—albeit in different ways. Hence, it is the differences, and not the similarities, in how these apparatuses engage the viewer that I find interesting.

How has the growing accessibility of art through the internet, social media, etc. changed the way you view technology and art working together?

I think this relationship is endlessly evolving and while it is exciting and productive of new forms of engagement, many of these new technologies are entering the consumer market before anyone knows much about how they will function as apparatuses—as I defined this term previously—and how they will transform our daily lives. Access to the plethora of these technologies is fundamentally changing all of us, and in ways we neither fully grasp, nor control.

Furthermore, our access to technology is affecting our relationships to the acquisition of knowledge, and to our understanding of how we inhabit the world. I wonder what the new paradigms to describe these changes will be called? For example, ‘collage’ was the dominant methodology/image operation of the 20th century. Each epoch had its own variation: from Dada and Futurism to Surrealism, Cubism and the unconscious, and there were many other notable collage operations along the way: Rauschenberg’s combines, William Burroughs and Brion Gysin’s cut-up novels, Pop Art and Appropriation Art, the Pictures Generation, and now the internet—wherein all mediums have permeable boundaries.

Some of the most interesting artists are making use of the fissures that this technological plethora makes possible. Today’s artists are producing new forms and exploring visual solutions while engaging with an art world that is much more global in its purview, and it is exciting to watch—which is why all 17 shows in Boston around the ICA’s Art in the age of the Internet are so interesting to see: a crash course in the myriad of possibilities.

What is your favorite thing to use the internet for?

Obtaining information of all kinds and news from around the world, especially news programs.

At a recent MIT lecture, you and George Fifield spoke about the changing landscape of AI, VR, and AR technology. Several artists and institutions are experimenting with how this technology can change the art-viewing experience. Do you think that in the same way we have a kind of curious nostalgia for early internet /video art, ten years from now we will look at early AR experiences with a similar fascination?

Maybe—this is hard to predict as I am not sure how long AR will survive given the current speed of technological innovation within the art world and the new forms some of these technologies can assume.

You have played an integral role in the “Art + Tech” city-wide initiative at MIT, the ICA, and the Gardner Museum. What has been most exciting about this endeavor? What do you think this initiative says about Boston and its art?

I think it is terrific for many reasons—two important ones are the way it has made the participating institutions more visible while also fostering a spirit of collaboration. I haven’t seen that in Boston previously.

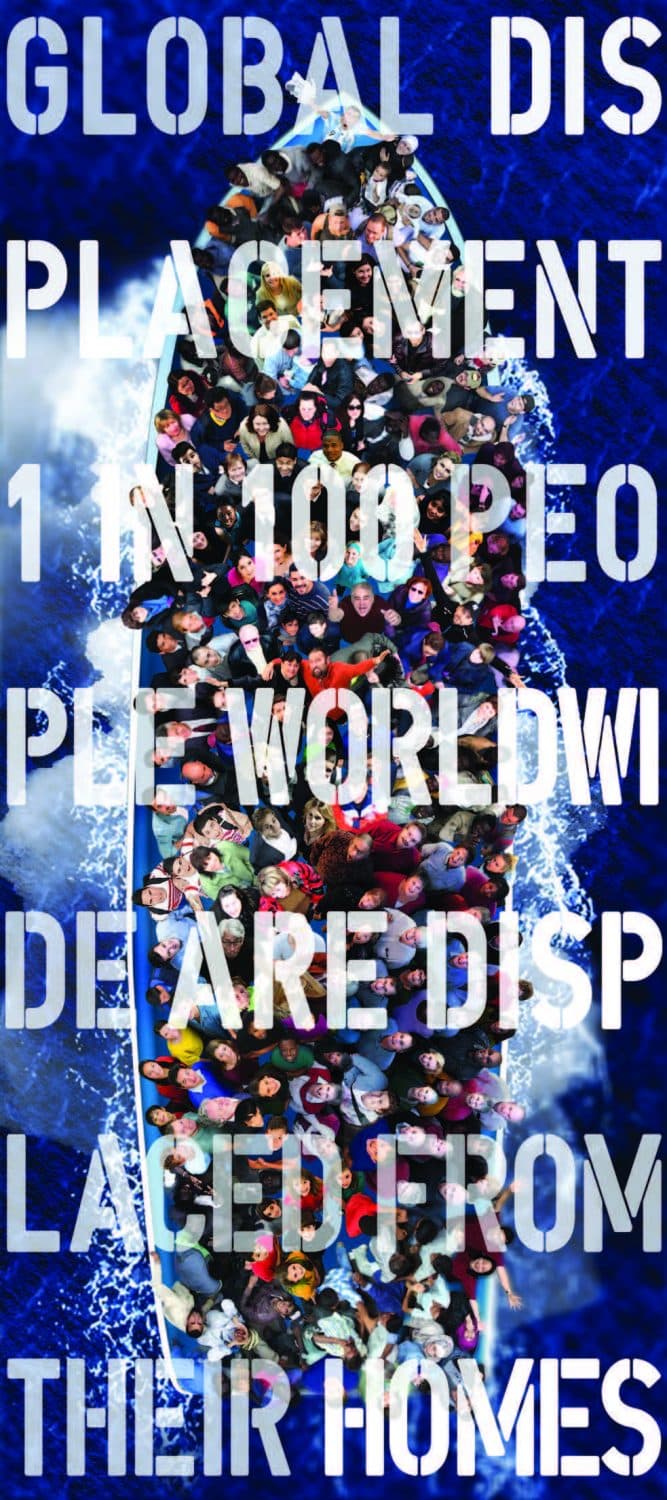

untitled: (Global Displacement: nearly 1 in 100 people worldwide are displaced from their homes), which is currently displayed on the facade of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, is quite an intense beacon of images. Can you tell us a little bit about what led you to create this piece? What does it mean for a piece of that magnitude to be displayed at an institution like the Gardner?

Sometimes I am haunted by images. That was, and sadly still is, the case beginning with the 2011 refugee crisis as gradually nearly 65 million people have fled their homes, escaping war, famine, and climate-ravaged countries, seeking a new life elsewhere.1

These images, often shot using drones, are poignant reminders of the trust and hope that even in the most dire circumstances remain abiding human qualities. Looking up, these asylum seekers greet the seemingly effortlessly hovering drone with a mixture of relief and elation—even though the drone is unmanned and not human, and even though the resulting encounter is no guarantee of a rescue or of entry into another country, and especially as a drone flying above your head in many parts of the world is a prelude to death.

In thinking about a façade project for the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, I was struck by the banner-like quality of the façade’s shape, and the way it can function like a beacon: drawing your eyes upward as you approach it from a distance, particularly when it is illuminated at night. Considering the rectilinearity of the façade, alongside the weather conditions, and the cycle of day to night, I imagined the images from the drone photos of asylum seekers transforming as they bleed into the sky, becoming even more pronounced at the golden hour when the day turns slowly into night…So many faces in the clouds beckoning you to a place beyond. A reminder that for so many of these refugees, there is no place that will welcome them.

My studio and I began working on this collage in the Spring of 2017. It became clear that in order to make a collage that was legible at 36’ x 16’, we needed better quality images for the faces. Meanwhile, as the summer progressed, a number of natural disasters happened across North America and Europe. These disasters are also fueled by climate change. We decided to replace the faces of the people in the collage with people who look like us. I also decided to add the title to the banner to make the content somewhat more legible. I wanted the viewer to spend time decoding the image, and then to slowly realize that the people looking out (so hopefully) look just like you and me.

This crisis is on-going and shows no signs of abating. As of October 2016, the last time such statistics are available, nearly 1 in 100 people are displaced from their homes and these numbers will surely increase. By orienting one of these boats vertically and populating it with the upward turned faces drawn from people who look just like you and me, the ISGM façade can act as a beacon: the faces forming a procession, illuminating the sky.

I’d like to wrap up by talking a little bit about your experience working, teaching, and exhibiting around Boston. How would you describe your relationship with Boston as a professor and as an artist?

I taught at MIT from 2002 to 2003, and then at Lesley University beginning in Spring 2005, although I have never lived here full-time. Boston artists still seem to graduate and move to other more art-centric cities, but this doesn’t mean that it could not become an art center. Los Angeles-based artists and their grad students have been staying in LA for 20+ years, as there is a long tradition of teaching in that city. Until recently the art market was not very present, and artist teachers have a very different profile in LA as many of the well-known artists have teaching jobs. I think that something similar could happen in Boston if instead of moving, artists stayed in Boston; that is, assuming they could get teaching positions and access to affordable studio space.

1 http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/10/05/key-facts-about-the-worlds-refugees/), 2018.

Judith Barry, untitled: (Global Displacement: nearly 1 in 100 people worldwide are displaced from their homes). Source: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/10/05/key-facts-about-the-worlds-refugees/), 2018.. Photo courtesy of the artist and Mary Boone Gallery.