In the age of advanced technologies, fingerprints and facial recognition are tools of surveillance; they register, mark, and identify bodies as they navigate between private and public spaces. Biometric technologies—measurements of the body used to develop dimensions of identification—have rendered skin color as a means to regulate the black body within public life. At the MIT List Visual Arts Center, Kapwani Kiwanga presents these concepts with “Safe Passage,” a body of recent works addressing the relationship between surveillance and Black histories in the United States. By utilizing sculpture and archival texts, her works grapple with the fugitive state of blackness from slavery, the Civil Rights Movements to our contemporary times.

Thematically speaking, Kiwanga’s works comprise grand, life-size sculptures. Viewers first encounter “Tripartite”, three vast black and pink dividers distributed across the room, and “Glow,” a series of black sculptures emanating warm soft light. In a collection of three pieces, “Tripartite” is displayed as a square that is then divided into two separate right-angle triangles. Composed of shade cloth, a semi-transparent screen used to provide coolness in hot climates, “Tripartite’s” material presentation guides and engages visitors. There is an allure in inspecting the visibility of other objects through the veneer of the screen. The screens, which can be examined from two sides, are visual manifestations of race as a symbolic dimension of surveillance within American history.

Ranging from four to six feet in height,”Glow” invites viewers to examine the smooth-textured surfaces of four light sources that serpentine their way across the room. “Glow” references the lantern laws, which permeated the public spheres of Colonial New England and New York City during the eighteenth century. In April 1731, “A Law for Regulating Negro’s & Slaves in Night Time” was amended to monitor the “Negro, Mulatto, and Indian slave” above the age of fourteen years after sunset. If they were not accompanied by a white person or carrying a lantern, their transgressions were met with a public lashing. Consequently, the body of the slave was governed under a system of racialized surveillance (1). “Glow” exposes the conditions of this system, which maximized the overseeing of the black subject through laws that were conditional to the concept of visibility. If visibility is structured under the reciprocity of recognition and autonomous modes of identification, then members of the black community were denied from it. With these static sculptures, the dematerialization of the figure embodies the outcomes of imposed racialization.

The parameters of the body politic and race are implicit in the color and form of the installation. Kiwanga’s selection of black as the surface color of the sculptures implies the visual appearance of skin as a marker of racialization and classification. Their rectangular and concave forms personify the static and fixed state of blackness as produced and inscribed through laws by the white gaze, which in turn affirms and sustains its power by exploiting and depriving the Black subject of bodily autonomy. Race inhabits the realm of the senses by becoming “image, form, surface, figure, and—especially—a structure of the imagination”(2). Alongside its formal presentation, “Glow” is framed by the horrors of racialization since slavery. The emission of light from the erect forms also implies their monumental potentiality; their stature substitutes for the flesh and perhaps corpse of the slave. Consequently, Kiwanga distorts and renders the state of blackness as deadlocked by surveillance, and difference as constituted by both flesh and skin.

In its tongue-in-cheek title and presentation, “Jalousie” is a partition constructed of vertical and diagonal two-way mirror slats. Kiwanga has repurposed a jalousie window into a work that invites viewers to meditate on the dualisms of recognition. Originally designed by Malden’s own Van Ellis Huff, jalousie windows became popular in warm and humid climates due to their ability to both maximize the inflow of air and provide privacy from the peering eyes of outsiders. Kiwanga has reconfigured the horizontal orientation of the window into a vertical partition with four rectangular parts composed of two-way mirrors. As the mirrors reveal and conceal the participants at hand, they orient our thinking to the formations of identity and self-consciousness, which rely on a structure of the recognizer and the recognized. The wordplay between the physical and theoretical nature of this piece is subtle, yet powerful as “jalousie” is also the French word for “jealousy.” In this regard, “Jalousie” functions as a symbolic contraption representative of the dialectical struggle of recognition, for if we are to seek mutuality and dignity, we are then required to identify the self and categorize the “Other.”

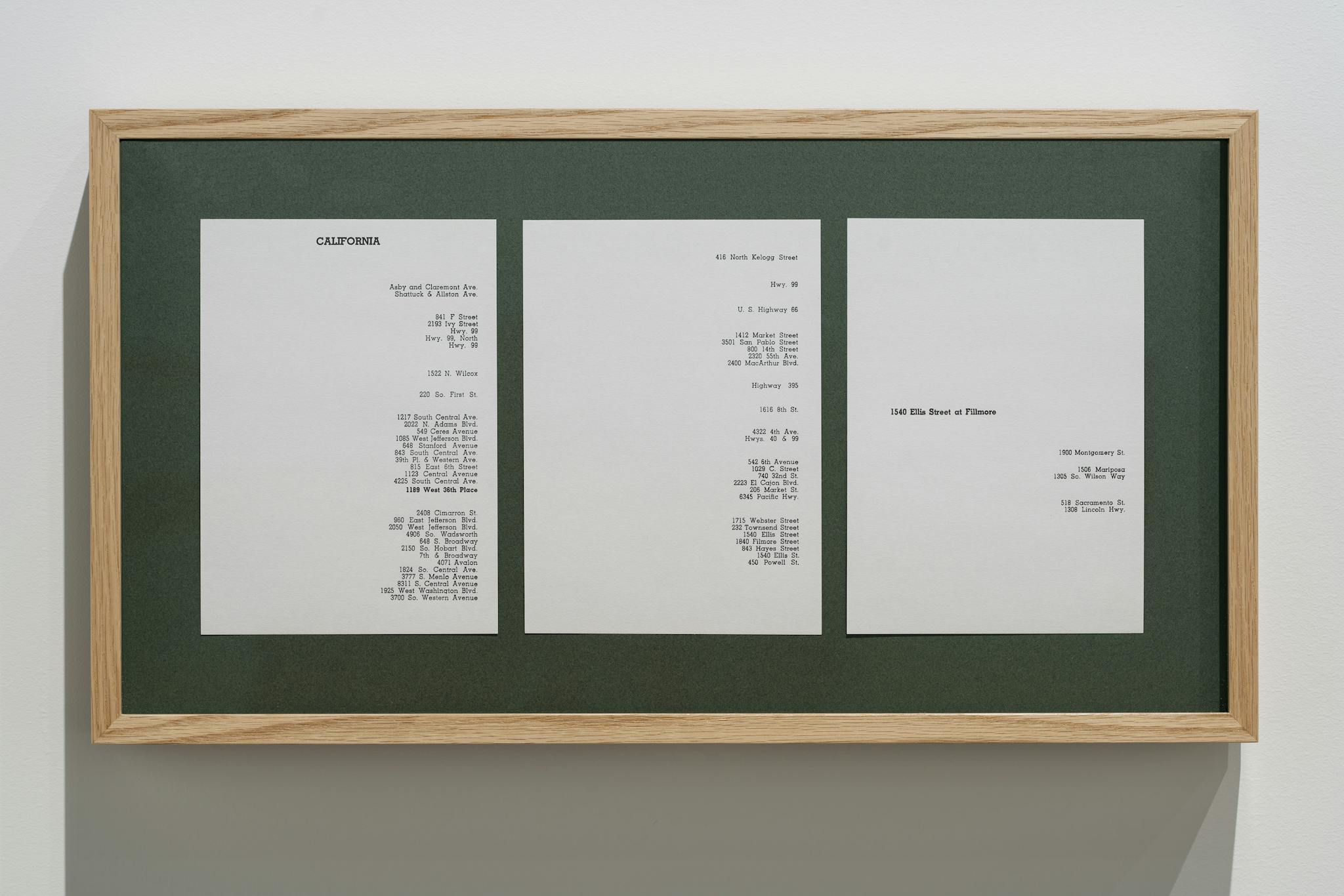

At the end of the gallery is an installation of “Greenbook (1961)”, a selection of 21 pages from “The Negro Motorist Green-Book,” an annual publication printed between 1936 and 1966 by Victor H. Green. The “Green-Book” aimed to give guidance to safe businesses and havens for African-Americans on their expeditions across America. Among the pages, Kiwanga has selected states such as New Hampshire, California, Maine, and Georgia, all of which are accompanied by street addresses that welcomed African Americans to their businesses. The names of the defunct businesses have been erased while the remaining addresses list businesses that still exist. Researching some of the addresses, I found that 615 S. Sunflower Avenue in Mississippi is the Riverside Hotel in Clarksdale, a lodging that housed legendary blues musicians and is better known as the deathbed of Bessie Smith in 1937.

“Greenbook (1961)” summons the archive as a medium to signify the fugitive state of African American motorists during the 1960s. Kiwanga has a background in anthropology, and her treatment of these pages is informed by her interest in archives, which is evident throughout her oeuvre (3). The assembly of these archival materials into a cohesive piece registers her practice as converting them into a new and authoritative system of knowledge. As Okwui Enwezor states in Archive Fever: “The archive achieves its authority and quality of veracity, its evidentiary function and interpretive power—in short, its reality—through a series of designs that unite structure and function”(4). In utilizing the archive as both form and medium, the installation retraces memories and the systematic permeation of white supremacy across the United States. Viewers witness the culmination of history and memory, yet they are reworked and therefore destabilized into new meanings. By eliminating the locations that no longer exist, Kiwanga transforms outdated information into new sets of data that are relevant to our time.

Kiwanga’s attention to the 1961 annual edition of the “Green-Book” is a notable model that reminds viewers of the history of racial segregation in public transportation. While observing the installation from one frame to the next, viewers are confronted by street addresses without any context. Their intelligibility is obscured, just as certain businesses on the state pages are whited out and therefore results in a relation of fungibility within the archive; that is, the information is already a reconstruction of history from a precise viewpoint (5).

The relevancy of the “Green-Book” has not been purely concurrent. Most recently, the “Green-Book” has made headlines within the film industry as the American director Peter Farrelly adapted a biographical screenplay of Don Shirley, an African-American pianist traveling across the United States along with his white diver, Tony Lip. Accolades of the film were met with criticism from the Shirley family, who lambasted the film for its imaginary narrative centered on a white person speaking on the behalf of a black person. Even Spike Lee attempted to walk out of the Oscars after it won three major categories, including Best Picture. Contrarily, the documentarian Yoruba Richen directed “The Green Book: Guide to Freedom” for the Smithsonian Channel, which respectful pays tribute to the development of the “Green-Book” and its impact among Black people across the nation.

“Safe Passage” constitutes acts of perception, reception, and recognition. Prior to experiencing these works, I had not encountered their historical factors and was therefore left with a curiosity of extracting their material and social-historical dispositions. In a nation that has functionally restricted the mobility of Black people, Kiwanga interrogates laws and events that have undermined African Americans on their quest towards self-determination. The archive becomes a potent tool in informing viewers on the structures of racialization and its outliers through the notion of surveillance. The works presented characterize the unfixed state of blackness throughout history. At the dawn of commercialized genealogical DNA tests and Kuwait’s considerations of DNA submissions from citizens and visitors, the relationship between privacy, surveillance, and the body remains tense. “Safe Passage,” then, is a locus threading these complexities, compelling us to reflect on measures of security within our own public—and private—lives.

1. Simone Browne, “The Making of the Book of Negroes,” in Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness,” (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), epub e-book, chapter two, Browne describes the concept of racialized surveillance as: “a technology of social control where surveillance practices, policies, and performances concerning the production of norms pertaining to race and exercise a ‘power to define what is in or out of place.’”

2. Achille Mbembe, “The Subject of Race” in Critique of Black Reason,. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), p. 32.

3. See works such as Maji Maji and Kinjitekele, which draw upon the history of the Maji Maji War during Colonial Tanzania.

4. Okwui Enwezor, Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art. (New York: International Center of Photography and Göttingen: Steidl, 2008), 18.

5. Marlene Manoff. “Theories of the Archive from Across the Disciplines.” Portal: Libraries and the Academy 4, no. 1 (2004): 14.

6. In 2015, Kuwait introduced the DNA Law in 2015 after the bombing of the Imam Sadiq Mosque that left 27 people dead and 227 wounded. The law required submission of DNA data from its citizens and visitors and failure to comply was subjected to the revocation of passports and travel. The law was later contested and repealed. See:

https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/10/17/kuwait-court-strikes-down-draconian-dna-law

Kapwani Kiwanga: Safe Passage is on view at the MIT List Visual Arts Center until April 21, 2019.