This exhibition review provides a conversation between the art of Stephanie J. Woods and the poetry of collaborator, Laura Neal. It is, in essence, an ekphrastic piece. Laura Neal wrote the featured poem, “We Are the Ones,” in response to an ongoing project by artist Stephanie J. Woods, titled, “Relax. Relate. Release.”(RRR). In this review, subjectivity and objectivity generate two distinctive voices that challenges duplicity and multiplicity, working to erase the line between truth and contradiction. This collaboration speaks to the impossible labor of transparency.

Online• Feb 04, 2019

Poetic Response: Stephanie Woods’ Art Challenges Racial Perception and Performance

Poetic response by Laura Neal on the occasion of Stephanie J. Woods’ Exhibition “Lavender Notes,” on view at Hudson D. Walker Gallery in Provincetown, MA.

Review by Laura Neal

Stephanie J. Woods, "Lavender Notes," 2019. Image courtesy of Johannes James Barfield.

Stephanie J. Woods, "Lavender Notes," 2019. Image courtesy of Johannes James Barfield.

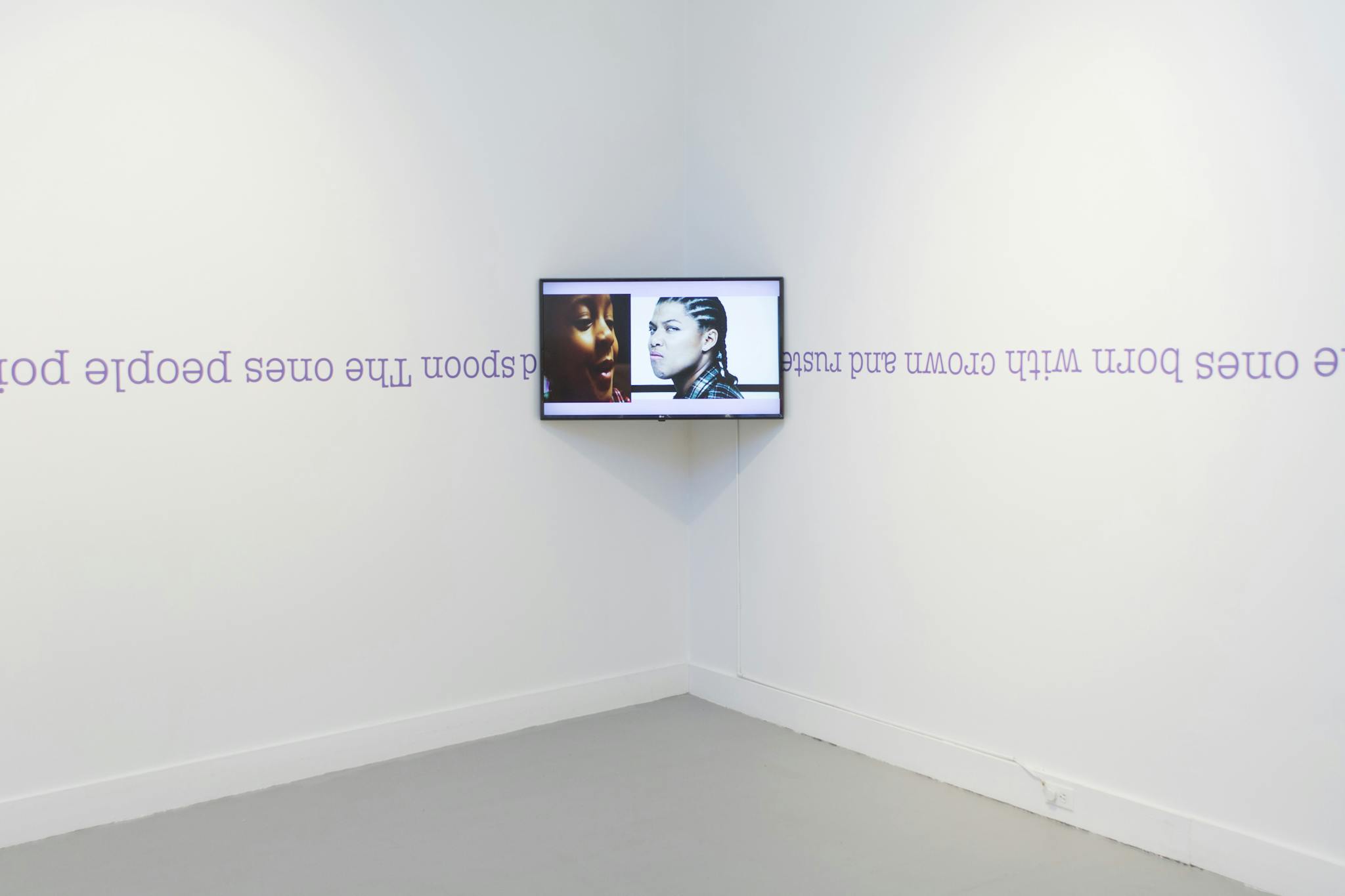

Stephanie J. Woods, “Adultification” (left) and “Sisters Educated and Liberated” (right) 2019. Image courtesy of Johannes James Barfield.

Overturned text, bonnet heads, and incantation. As strange as it sounds, nothing feels more relatable. In fact, at first glance you may think the exhibit is pretty sane, nothing too wild or other-worldly, but then the closer you look, as soon as you take that moment to invest and investigate, it stings you like those cuts you didn’t realize you had until you washed your hands. Artist Stephanie J. Woods is critically engaged with black performativity, both with self and other. On view at Hudson D. Walker Gallery in Provincetown, her exhibition, “Lavender Notes”, challenges duality and reveals the contradictions of identity. There’s an interrogation of the body; how multiplicity doesn’t necessarily mean ‘well-rounded’, instead it’s more akin to struggle. From the overturned verses that wrap around the gallery walls to the installation of her bonneted figures, one thing is clear–resistance.

Upon entering the gallery, a wall-sized portrait of a group of black teenage women sits squarely in the center of the wall. They are dressed in matching camouflage and posed facing a camera— and in turn—the viewer. The portrait, which has been printed on fleece fabric, is bookended with the overturned purple text that stretches the width of the wall. Consider the purpose of camo wear. It’s designed for disguise and for coverage in war; worn solely for the goal of not being seen. Within the context of this show, camo wear is a direct commentary on identity and visibility. Each of the young women are unique in their physical responses to the camera; they pose individually, they smile with subtle differences. All of them, however, are synonymous in the fabric of coverage. There are many African-American cultural norms that facilitate the invisibility of black women, such as these proverbs: ‘you should be seen and not heard’ and ‘only speak when spoken to.’ Camouflage gear presents the conflict of association with power and liberation, as the title of the installation suggests, may not provoke a response on the spectators initial view, but when re-viewing the piece, my instinct was to pause and consider the everyday occurrences where the choice to be seen or unseen is not your own. This is just the surface.

Stephanie J. Woods, “Frontal” stretch solid mesh, gold foil, vinyl, and repurposed mirror, 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.

Moving through the exhibition space, the overturned text on the walls continues to transform. At one point, the text is becomes entirely jumbled—barely legible as it is crammed inside a wooden frame and draped in lavender colored fabric. An audio poem, written by poet collaborator Laura Neal, plays on an endless loop across two speakers. Neal recites the poem through one speaker and Woods echoes the poem through the other speaker. Attached to a sample from Willie Hutch’s “Mama,” the result is incantation. A spell, trying to will something from the invisible.

In the corner, a video installation is looping the image of a young black girl juxtaposed to the Cleo character from the 1996 film “Set It Off.” The pairing of these women serves as a commentary on sociopolitical expectations. It’s difficult not to trace the thread of coverage in this piece too. In the split-screen video, the girl is playing in a home with small, hard figurines that are likened to rooks on a chessboard; she is static in her position. On the other side of the screen, Cleo is in motion; she is in a constant escape, while the figures of law enforcement are either giving chase or aimed with weapons drawn. The force is greatly disproportionate to the threat. Displaying this scene on a loop creates a narrative demonstrative of systemic issues involving criminalization. The young black girl likened to trouble is a bleak but not invalid perspective. The social, cultural, and economical traps prevalent in the film “Set It Off,” persists as reality for many in the black community. The video installation forecasts the child’s future by measuring the barriers and expectations that are already being built for her through systematic factors. Providing just one vantage point, the dual video emphasizes the impact of self-sacrifice and mass incarceration.

Stephanie J. Woods, “Adultification,” 2019. Home video footage with video footage from the motion picture “Set It Off” (1996.) Image courtesy Johannes James Barfield.

Follow the overturned text to the feature piece of the exhibition and you’ll witness three large portraits of the artist wearing bonnets that obscure her head completely. Each bonnet displays a different word or phrase such as: “Make Magic, Create, Heal.”

Those words are encouraging and inspirational, but here they feel more like burden, like an impossible labor, like harsh expectation. Especially contrasted against the body held together with folded arms and a sharp red shirt. Artist Stephanie J. Woods is a southern-based artist and this piece is especially rooted in the tradition. The color red is significant in this piece. Not only is it an emotional signifier (love, anger, danger, blush, blood, hell, etc.) but historically, the color red was commonly used to dress the “mammy” figure—a detail the artist informed me of after viewing. The mammy caricature, a figure of the Jim Crow era, portrayed black women as happy slaves while only serving the misconstrued interests of mainstream society. Whether a doll or a poster, given the position of the body as object, this association is pivotal.

Stephanie J. Woods, “Lavender Notes,” 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.

Stephanie J. Woods, “Lavender Notes,” 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.

The materials Woods utilizes present yet another point of contestation. While the bonnet portraits are printed on soft satin, the frame is upholstered with rough burlap dyed in sweet tea. The juxtaposition of a luxury satin presents with the utility of burlap challenges us to consider our own composition. Scattered and scrambled on the frames are gold-embossed words. These words generated from an ongoing project Woods has titled, Relax. Relate. Release. (RRR). The illegibility of the words on the frames raises questions about disclosure. How much of ourselves should remain guarded? How much released? How much is tragically lost in translation? For women of color especially, coverage and being birthed into coverage is a daily and stressful reality. The RRR project inspired my poem “We Are The Ones,” which became a collaborative piece.

We are the ones…

–for SJW

We are the ones who learn to sacrifice

before learning to fight

the ones who lead in the shadows

the ones who survive

the ones who’ll organize the world

set it straight

the ones who make more with less

the ones who make struggle

look like a silk dress

the ones who understand and overcome

the ones who pray and give praise

the ones born with crown and rusted spoon

the ones people point at and to

the ones, twos, and threes, we top everything

the original ones, originators of beauty

origin of daughters and sons.

The lines in bold are the ones Woods appliquéd overturned on the gallery walls. Spectators tilting their bodies in an attempt to read the text shown as a live enactment of rearranging perspective, thereby individuals became an active part of the exhibition.

Artist Stephanie J. Woods has developed a body of work with just a few bones from her African American culture. Her critical discernment with resistance is polymorphic. The exhibition is disheveling in its review of the body as object and how performativity is engrained in black identity, both as progressive and to a fault. The natural/unnatural dilemma of being trapped in the perception of the forced, the forcer, and the effects of enforcement from historical and societal pressures. The exhibition has a clever subtlety. It doesn’t need to yell at you. It is as approachable and potent as lavender. I left the show feeling both comforted and splintered coming to terms with the hard realization that coverage is a continuum that aids in both black erasure and preservation (i.e. bonnets, plastic on furniture, underground quilts, code-switching, etc.). Risk and resistance are on display at Lavender Notes. The dangers of conformity to societal pressures and demands; how that commodifies the body. The trouble of adopting embodied behaviors transfiguring the body into object; both leading to classifications of either stereotype or traitor. The hard and contradicting question: Which one would you like to be?

Resist.