Moko Fukuyama’s public sculpture See the Forest for the Sea (2024) is on view at Silver Eel Cove on Fishers Island, NY, through December 15, 2024. Resembling a jumbo exploded tackle box hung with vibrantly painted lures, the work is an ode to fishing. A Kind of Pain (2019), her video and sculpture installation that meditates on fish, angling, and humankind’s aquatic origins is concurrently on view at the Filling Station on Fishers Island until July 31, 2024. Produced by Lighthouse Works, an organization that supports artists and writers and connects them to Fishers Island, See the Forest for the Sea is its eleventh annual public art commission. The island, despite its physical and cultural proximity to Connecticut, is New York State territory and has been a subject of dispute between the states for decades. For a perfect New England summer day trip and to see Fukuyama’s work, visit Fishers Island by taking the ferry from Waterfront Park, New London, CT.

Over the past decade, Fukuyama has developed a sculptural practice that involves locating and reclaiming fallen trees that she then carves and paints into reanimated creature-like forms. Her surface treatments are equally influenced by scenic art and her interest in custom car aesthetics. Born in Chiba, Japan, Fukuyama came to the US to enroll in the Memphis College of Art in 2000. She lived in Brookline, MA, for a year while attending the School of the Museum of The Fine Arts. Currently, she lives and works in Brooklyn, NY, and is working on a new commission for the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum opening in the fall of 2024.

A few oak trees brought us together, indirectly. Downed by Hurricane Sandy, their trunks comprised Shrine (Hell Gate Keepers), Fukuyama’s proposal for the exhibition “Sanctuary” which I organized at Socrates Sculpture Park in 2021. Here we discuss our shared interest in challenging a binary conception of nature and culture, material life cycles, and collaborating with the environment.

The following conversation has been edited and condensed.

Jess Wilcox: Tell me about the origins of your first fishing lure piece, A Kind of Pain.

Moko Fukuyama: Around that time is when I started sport fishing. My partner, Aaron, and his brothers who lived down in Tennessee are huge fishing people. Fishing is also huge in Japan, but it’s something I never thought I would get into. I started going fishing with them and was immediately intrigued by the lures, even more than the act of fishing itself—just beautiful sculptural objects. I realized how these lures attract fish in their natural habitat by manipulating them. We don’t know if fish are going for them because they want to eat them or fight them, or because the lure is so attractive. ‘I’m going to go for this, for whatever it is. I’m going to check it out.’

JW: What kind of lure materials do you interest you?

MF: It’s usually plastic, rubber, silicon—all kinds of materials. But older lures used to be carved out of wood. My partner’s father gave me his father’s old lure which is made of solid wood and is painted by hand.

JW: In contrast, the silicones and a lot of the plastics have a translucency that to me seems to emulate aquatic creatures. But it isn’t just aesthetics you play with; you also enlarge the fishing lures so that their bodies approach or exceed human size. Can you tell me how you think about that?

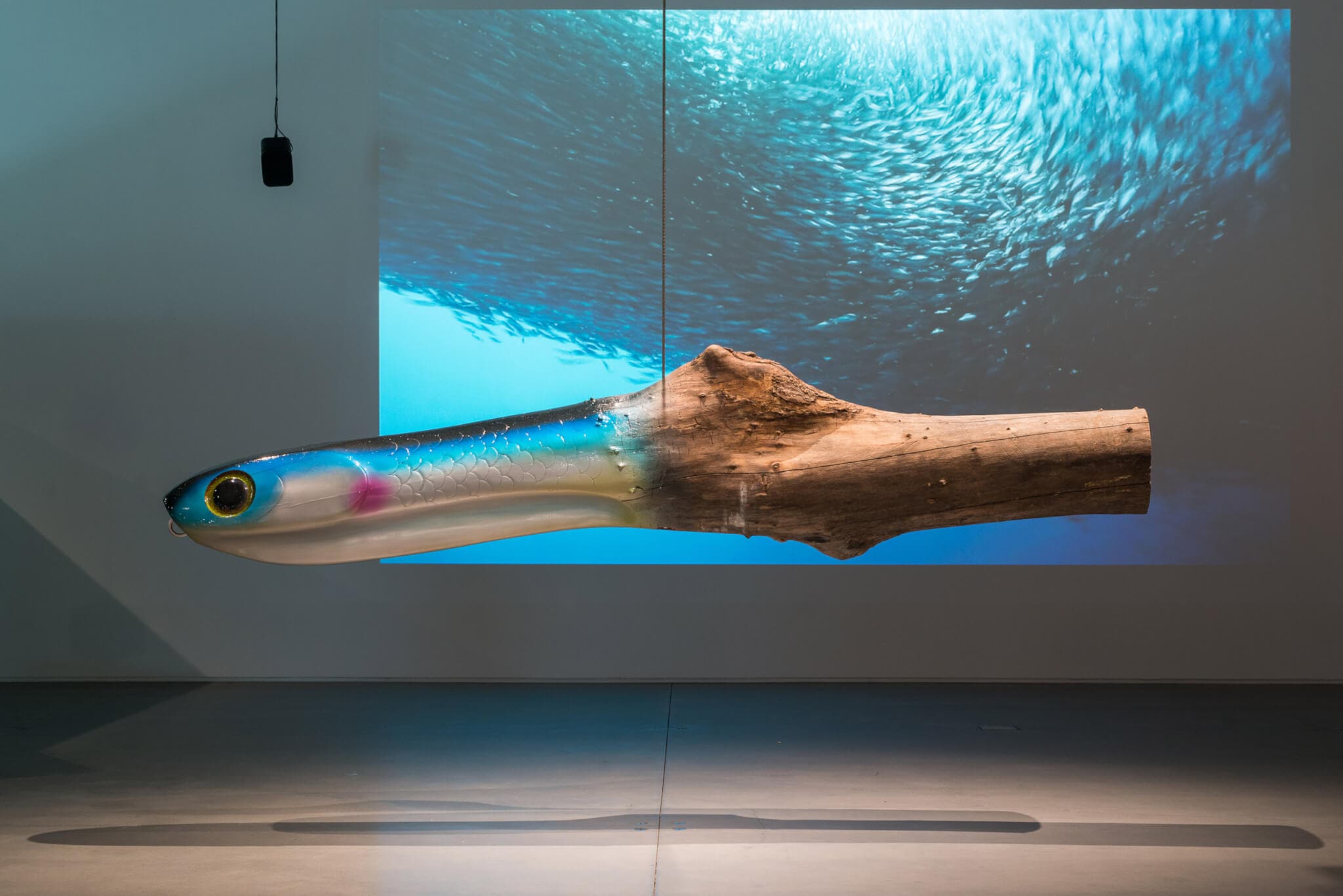

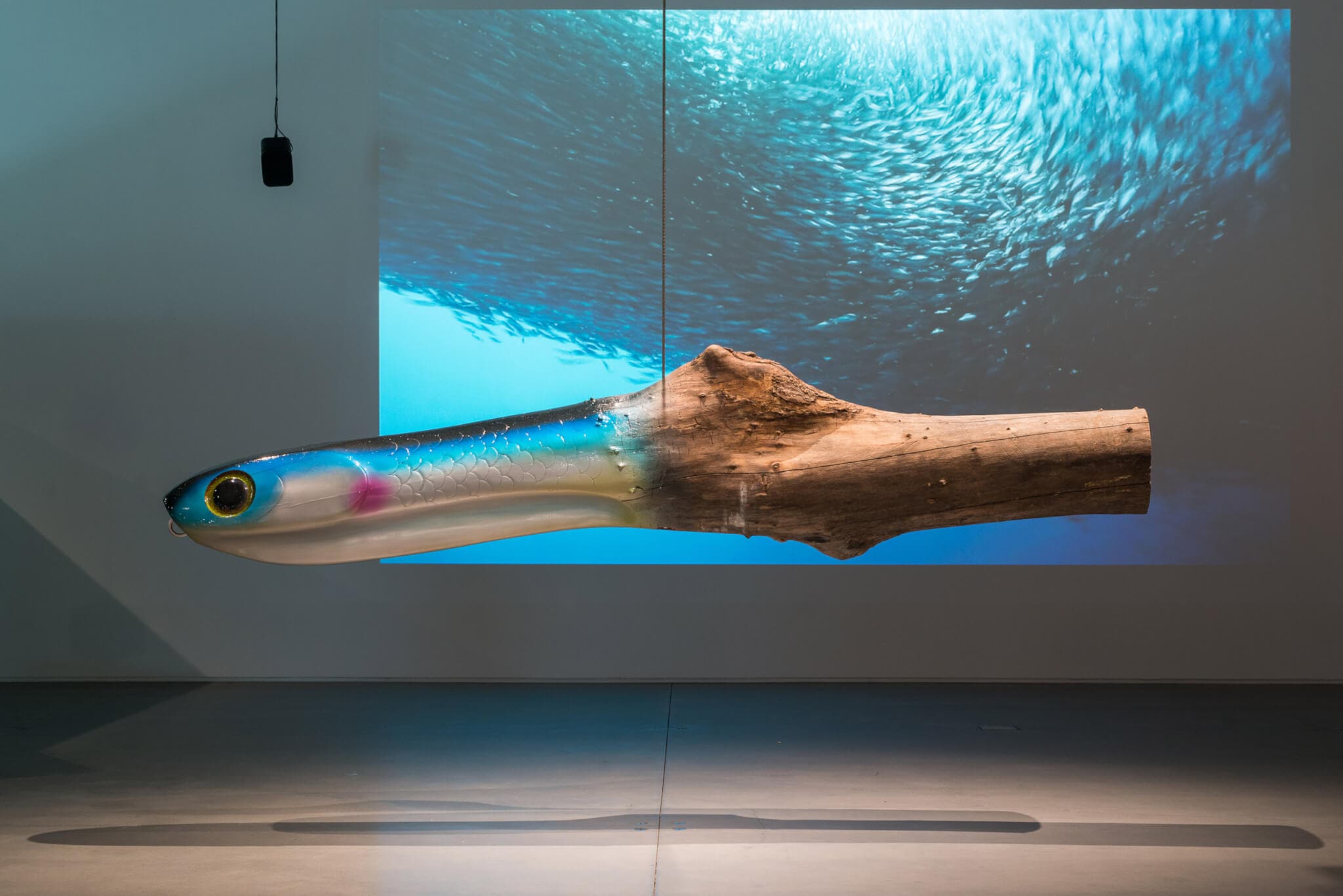

Moko Fukuyama, A Kind of Pain, 2019. Photo by Tahir Carl Karmali. Courtesy of the artist.

MF: Good question. I dunno. Since I was very young, I’ve had a problem making small things. My calligraphy teacher would always tell me to write smaller because it didn’t even fit on the paper. My stroke was too big. It’s something about how my body moves that’s always a little bigger than myself.

JW: I love that. It’s really inherent and intuitive.

MF: It is, but I am learning to work on a smaller scale. This tackle box for Fishers Island is a good trial. As a sum it’s large, but it has parts that can be carried.

JW: Since we’re talking about tackle boxes, I was wondering if you could talk a bit about the first one that you made.

MF: Making a tackle box is something that had been simmering in my head since A Kind of Pain. It’s a natural progression—there’s a tackle and I need a container. So, in 2021, during my fellowship at Franconia Sculpture Park, I made this horizontal tackle-box-like garden with gravel and steel edging. I used fallen timber which I found locally in Minnesota and included several sculptures made by the artist Robert Ressler. The park had this area dedicated to discarded artwork and they encouraged artists to reuse the material. That is a questionable practice, to be honest. The staff said that I can use anything that I found there, and I found these beautiful carved fish sculptures.

Moko Fukuyama, Tackle Box, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

JW: And you had already been making fish, so in a way you found your collaborator.

MF: Exactly. They’re more literal fish-looking sculptures but are beautiful. There was something strong about them. I was like, ‘Whoever made this piece is really skilled because it’s really hard to carve wood in the way he did.’ The park told me the artist had discarded it and I could use the piece as scrap material. Instead of repainting or cutting it up, I cleaned and placed it next to the sculptures I made from the fallen timbers. In researching the artist, I discovered he had shown public art at a lot of New York institutions in the 90s but was unable to locate him. That version of the Tackle Box is a meditation on what happens to art after the glorious exhibition period. It asked questions about how work transforms from being wanted to unwanted. Since then, Robert reached out to me. He appreciated that I treated his work with respect, resurrecting it in a way.

JW: That speaks to the trajectory of all objects and materials—the fact that you have used already fallen trees, and the tree goes from being one thing when it’s alive to another when it’s dead.

MF: And a tree, when standing, it’s glorious and it’s beautiful and people love it. But once it falls, they’re like, ‘Get that out of my sight.’ Right?

JW: It becomes an eyesore to some. That’s a good transition to the currently on view newer rendering of a tackle box at Fishers Island. Instead of laying it horizontally, you’ve tipped it vertically. It’s kind of a skeleton because you can see the landscape behind, but it also recalls retail design. So, it’s more of a conceptual tackle box than a representational one.

MF: I was really fascinated by the in-betweenness of Fishers Island. It’s in New York and Connecticut at the same time. The island is really manicured and also very wild. It’s both private and public and in between so many different waterways.

After I made the horizontal tackle box at Franconia, I thought about how I could make it vertical, perpendicular to the eye. I had an issue making long sculptures because when you make them vertical, they’re automatically phallic. And when you carve wood, it’ll automatically look like a penis, right? Every single sculpture I’ve made from a log has looked like dildo. You’re like, ‘Oh God, here it goes again.’

The artist working in her studio on production of See the Forest for the Sea. Photo by Aaron Suggs. Courtesy of the artist.

JW: That’s a hilarious observation, especially as we’ve previously discussed how every log has a story. Would you be able to walk us through some of the different logs, trees, and trunks? Because there are different species that you’ve brought together.

MF: Yes. The sculpture [See the Forest for the Sea] contains several species. It has oak, pine, ash, cherry, sycamore, birch, cedar, walnut, and a couple of driftwood. All the wood comes from New York state—some from New York City, Long Island, and upstate New York. The ash tree piece was given by my friend Robert Rising, who has a lumberyard in Dover Plains, New York, and who has embraced the ‘Black Lumber Jack’ nickname in his business branding and media presence. It was scrap cut off a bigger piece. Ash is on the way to extinction in North America because of the emerald ash borer, an invasive insect. One of the lures has a lot of chewing marks by the ash borers. I deepened the scars. Basically, I follow what the ash borer marks and, with the Dremel, trace its chew marks.

JW: It almost looks like coral, which is amazing. But I also started to think, ‘Oh, this is a sculpture collaborator of Moko’s.’ The emerald ash borer is actually a sculptor too.

MF: Yeah, I’m thinking, ‘Why did he make a turn here?’ and ‘What’s the logic in making such a shape?’ I’m sure it’s just following whatever tastes good to it. But it’s interesting. They make such beautiful markings. I made a sculpture that resembles the ash borer beetle while inspired to shape something that resembles a car. All those insects, their exoskeletons look like sports cars—the curvature, design, and recent manufacturing techniques. It’s something I will explore further. I’m interested in the idea of aero- and fluid-dynamics, and how that shows up in design. The car from ten years ago is a lot rounder. Now it’s cut differently. It’s more bullet shaped. And it’s funny because I don’t know how much gas mileage we save. Is it really to save the environment?

JW: Speaking of the aerodynamics, I really loved the jointed fish. Positioned as it is, it’s not just a sculpture, it’s a mobile. I don’t know if you’d been thinking about the wind.

MF: Yeah. Most of them are not anchored. They’re suspended, so they definitely interact with the wind and light. It’s a bit risky because who knows what would happen in a storm. But I work with engineers to make sure the piece is strong. It interacts with the ocean spray and dances in the wind and makes the work even more alluring. … I’m also interested in manga comics. That’s something I have explored in my work and will probably go back to.

JW: I can see those compartments as cells of a comic. It gives it an almost narrative feel. That’s why I asked about the stories behind each log, because within that little compartment, it’s a frame, a contained world that you want to get into.

MF: Absolutely. Each compartment has its own story, and the viewer can move through it by walking around it. It’s almost like a 3D manga comic.

JW: One of the cells has two long members, and a kind of trumpet shape and a knobby creature are next to each other. Could you talk a little bit about those pieces?

MF: Those two pieces come from the same sycamore tree that was chopped down in front of my studio. The design was so intuitive. I don’t really think about making things into something that they’re not. My intention is always, ‘What can I do to make the most of what this tree already looks like or its interesting characteristics?’

JW: It resembles… I don’t know what kind of animal.

MF: A lot of those sculptures resemble amphibious life. I am really attracted to the species that came from the ocean or came from land and went back to the ocean, like the whale.

JW: Yeah, in A Kind of Pain you mentioned that humans evolved from the water. I can see this in the lure which was part tree, part creature, suggestive of this long process of mutation that goes on in evolution. This reminds me of Shrine (Hell Gate Keepers), which you made in response to a prompt about the idea of sanctuary. The piece refers to Shinto shrines and beliefs in the animate nature of all things. Does that partly inform what else you’ve been talking about in terms of the transformation of living and nonliving things?

MF: Yeah, absolutely. Where I grew up in Japan, Shintoism is one of the major religions. It is a polytheistic religion and every part of the earth is considered as God—the wind, soil, water, trees. It’s something that’s so inherent. I definitely have a belief system where nature is God and a shrine is a structure or an area that contains holiness and some kind of higher power.

Moko Fukuyama, Shrine (Hell Gate Keepers), 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

JW: Did you use any wood from Fishers Island?

MF: I did. The big eyeballs in the left cell [of See the Forest for the Sea] are the pines from the island and the small ones too. They are a mixture of woods but most are cherries. All the fallen trees from the island go to this one waste management facility there. The staff at the facility kindly gave me access to all the trees there and let me mill them on site.

JW: I thought maybe we could end with talking a bit about the title of the piece and why you chose it. See the Forest for the Sea, it reminds me of that phrase, ‘See the forest for the trees.’

MF: Yeah. It’s a play on the phrase for sure. My intention through this work is to be able to see the ecosystem from all sides. I am also questioning why we think everything is connected. Because of all the information overwhelming us every day, everything seems to be consequential. But maybe that’s not the right way to think. I’m suggesting looking at the big picture and small picture simultaneously. Rather than just claiming that everything is connected, I’m interested in productive thinking and solving problems. I took fishing as an entryway to think about something larger and abstract. I often play with micro versus macro. In sum, I titled it thinking we should see ecosystems from many perspectives.

JW: What are you most excited to see for the piece now that it’s been installed and will be up through December?

MF: I’m excited to see how the piece will interact with the environment and how it weathers, if it changes—hopefully for the better. A lot of structures only get more beautiful with the patina of age. The issue of artwork conservation is part of the story of how the artwork will live in the world for a long time. So, I’m not scared of that. Any issue that might come, I will deal with it. The trees already lived quite a long time before I interacted with them. So, I have a sort of trust in the tree to withstand, to do what it does.