What will it take for the field of arts and culture, particularly in the public sphere, to truly support Indigenous peoples and Indigenous artists in our city? In the nearly year and a half since my article “Unseen Dimensions of Public Space: Disrupting Colonial Narratives” appeared in Boston Art Review’s Issue 04: The Public Art Issue, I’ve been asking this question. Reflecting on my experiences as an artist working at the intersection of creative expression, public service, and Indigenous peoples’ cultural fortification, I see the struggles of this past year edging us closer to attaining cultural self-determination for Native people. To share a snapshot of this progress, I have put together a timeline of some significant contributing events that have occurred since the article’s publication, alongside several of my related projects.

My own creative practice is sustained by my Dakota heritage and philosophy, and they shape the organizing and cultural work I do in my communities. A great deal of my work points to gaping imbalances I perceive in the dominant society’s approaches to the world that stem from our shared colonial roots. For example, my public performative character, Earthling, uses humor and unconventionality to remind us that underneath our closely held ideologies—underneath the systems that capitalize upon us and colonize us—we are earth-based beings. In fact, we are not just of the Earth; we are the Earth.

I find commonality with people from diverse backgrounds who sense these imbalances and seek remedies to them. In this year of pestilence, I’m reminded that epidemics are emblematic of the colonial legacy all people in these lands share. In the 400 years since the notorious English separatists arrived in Patuxet, now known as the town of Plymouth, to claim the commonwealth of Massachusetts—and to rather unoriginally name this region New England—too much has been taken, and too much continues to be asked of Native people by the beneficiaries of settler colonialism. The United States is still actively working to terminate tribes here. In March, the federal government ordered the disestablishment of the Mashpee Wampanoag tribal reservation, which is just a short distance from Boston. Colonization is not resigned to history alone; it is a process that continues today through the ongoing occupation of these lands. A lack of recognition and respect for contemporary Native peoples in the public sphere contributes to ingrained public ignorance and apathy that enables these injustices to persist.

By scrutinizing the trajectory of colonization, we can trace the large-scale crises we are facing—a worldwide pandemic, pernicious institutional racism, extreme economic inequality, massive ecological destruction, and intractable global climate change—back to it. Our failure to solve them implicates the cultural foundations of a society unwilling to disentangle itself from the hydra of settler colonialism. The cultural landscape that has arisen from the ashes of its violent upheaval, and the subsequent machinations of social engineering that have encouraged our country’s citizens to excuse or forget the atrocities that founded it, continue to dispossess Indigenous peoples and reverberate across the fields of art, culture, science, technology, policy, and economics.

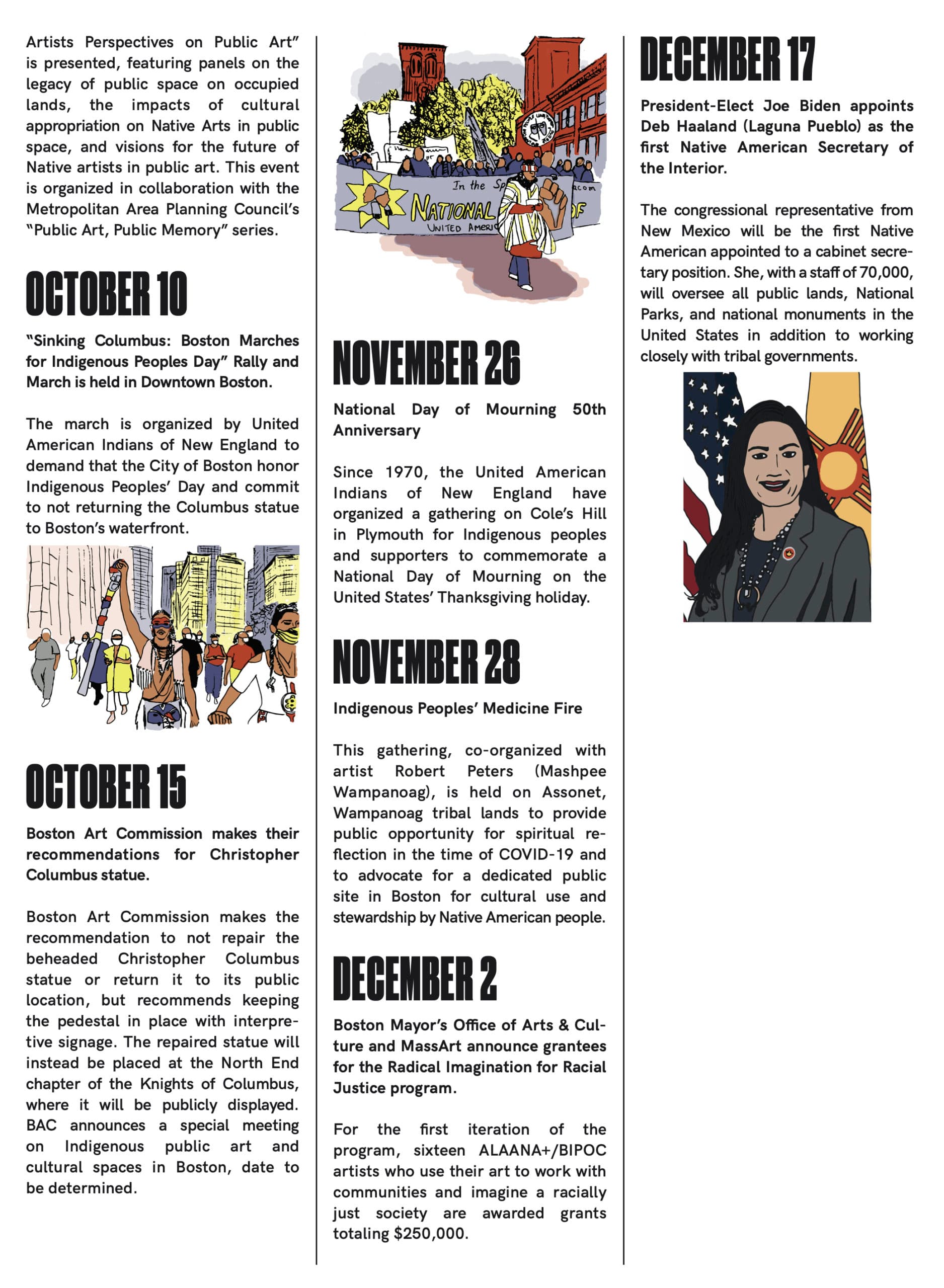

Today, I wonder what percentage of our city’s population knows about the Massachusett tribe upon whose lands Boston occupies, or the Nipmuc and Wampanoag peoples of our region. The public invisibility of and racism toward Indigenous people in our midst is also an epidemic, and yet, we owe so much to the original people of this land. This dispossession is on full display in public spaces awash with symbols, art, memorials, monuments, and other infrastructure celebrating colonization and slavery and promoting the myths of white cultural supremacy. These manifestations reveal the faulty foundations of our culture and pose impediments to the essential work of extricating ourselves from prevailing colonial attitudes and setting a new course. The public turmoil we’ve been through this year has dislodged some of this infrastructure. Most significantly, the reinvigorated Black Lives Matter movement has been a monumental force pushing Americans to recognize the foundational injustices of our systems in order to transform them.

So, I ask again: what will it take for the field of arts and culture, particularly in the public sphere, to truly support Indigenous peoples and Indigenous artists in our city? To approach the question, we must take our next steps together toward an honest reckoning with the entrenchment of Western cultural supremacy, which is the root of racism in our institutions. We must confront the impacts of public ignorance of history and current affairs have had on Indigenous peoples through art, culture, and education. These are key ingredients to a collective commitment to address the persistent trauma and disparities affecting tribal communities that stem from the genocidal beginnings of our society. The benefits of this strategy will not be limited to Indigenous peoples, either; they will contribute to a better future for all.

As we reel from the ill effects of our country’s mishandling of this pandemic, it has become clear that we are much more connected to each other than we have been led to believe. The virus has undeniably exposed the profound failings of our cultural, economic, and political institutions’ misalignment with, and lack of respect for, the systems of the natural world. Our next question should be, how can we build a society that recognizes our inherent interconnectedness? I continue to have faith in the power of transformative collective vision and creative action to amplify not only the contributions of Indigenous peoples, but all those who are marginalized by dominant systems of power.

From Seattle to Minneapolis, cities across the nation are making inroads in alleviating cultural inequities through public arts programming for Native people. This work is beginning to happen here in Boston, as well (see the timeline ahead for a rudimentary sampling), but much more must be done. Colonial forces have been active in the greater Boston region for more than 400 years, and we can and should be at the forefront of confronting their widespread harms through the arts. To achieve this, let’s infuse a critical orientation toward the legacy of colonization into our work and create programs that enable Indigenous peoples to lead and be heard.

Timeline of significant events since Unseen Dimensions of Public Space: Disrupting Colonial Narratives

Edited by Maya Rubio