Jo Ann Rothschild is a painter in the sixth decade of a career that began in her time as a student at Bennington College and deepened during years in Western Massachusetts in her early twenties. She arrived in Boston for graduate work at the Museum School and, in 1993, was the first recipient of the Maud Morgan Prize, given by the Museum of Fine Arts to an outstanding female artist in the city. Thirty years later, her airy fourth floor studio on Albany Street in the South End is packed with canvases of all sizes, on which she explores her medium through an expressive, abstract, and often hermetic vocabulary of marks.

This issue’s theme, “Emerge,” seemed an odd fit for an artist so established in her career and voice—and also perfect for someone who has so cleverly skewered the perpetual emergence of women artists in an art world unprepared to meaningfully support them.

Michelle met Jo Ann earlier this year at a program on the late Austrian artist Maria Lassnig that Michelle had convened at the MFA (where an exhibition of some of Lassnig’s films, made in New York in the 1970s, was on view). The discussion of Lassnig’s oeuvre—better known for her powerful, intelligent paintings—focused in part on the gendered experiences of being a woman in the art world in the late twentieth century.

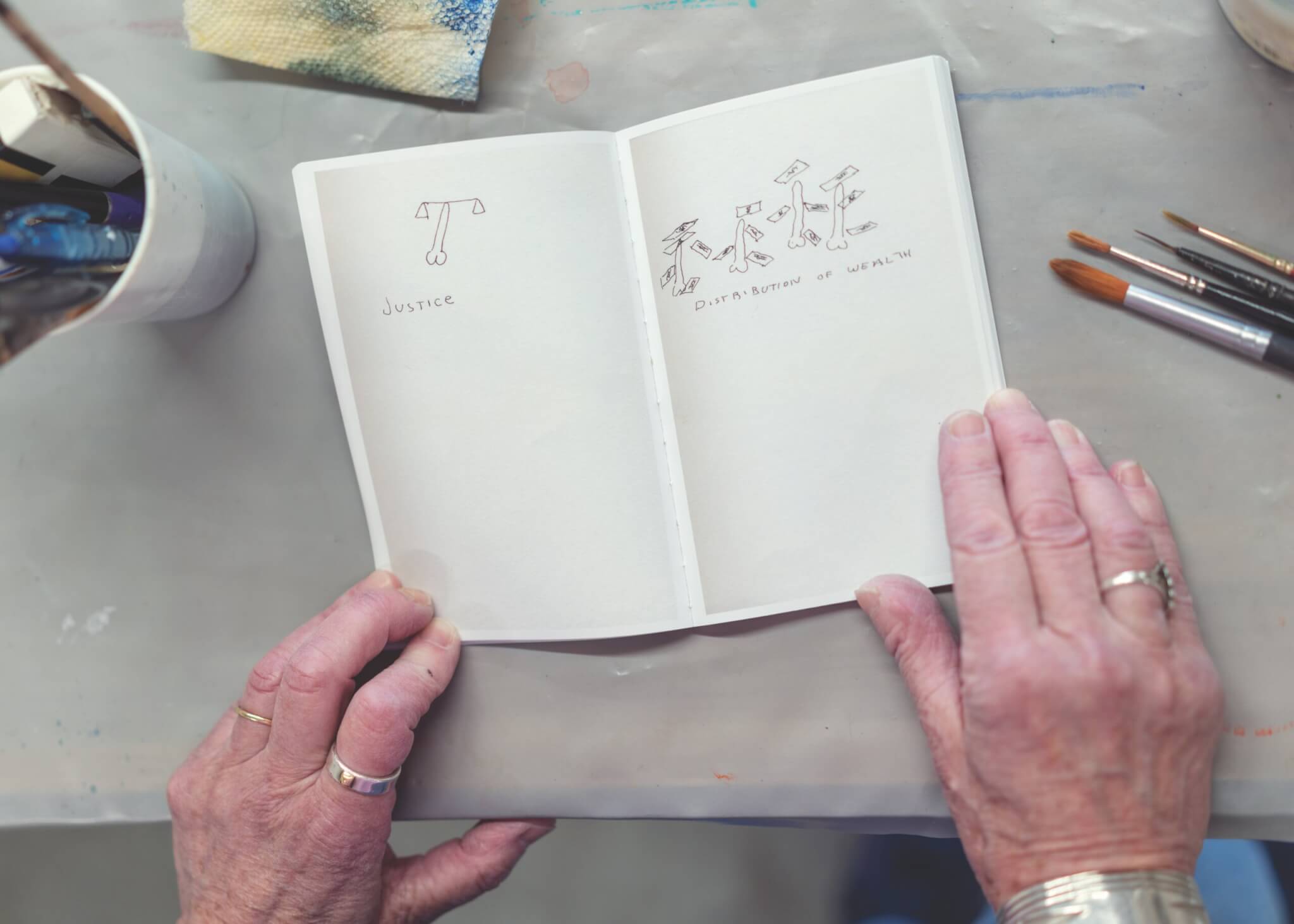

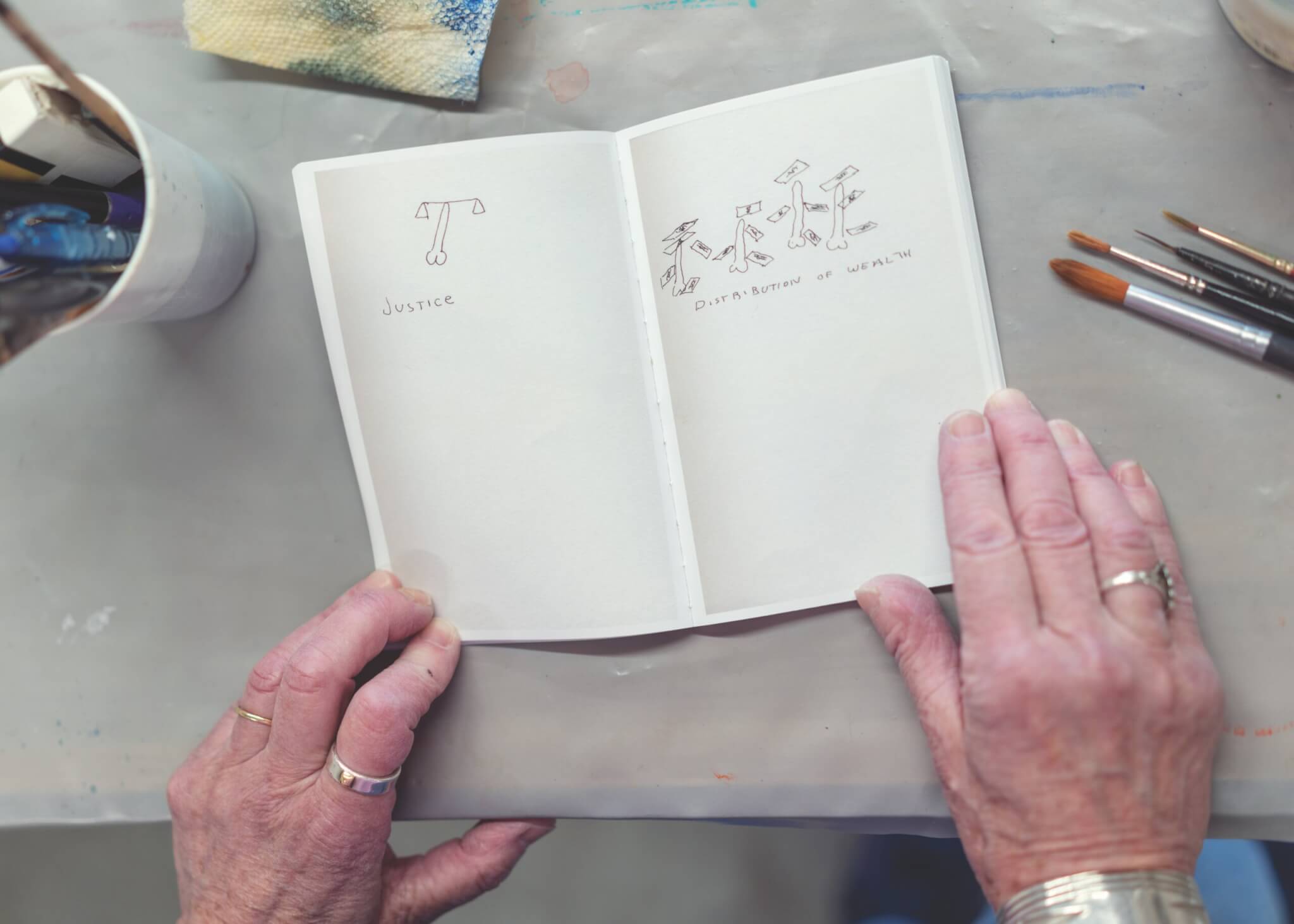

Jo Ann found Michelle at the end of the program to say how much the conversation had resonated with her. A few weeks later, she sent a copy of her spicy manifesto, The Book of Penis!, to the museum. It’s full of tongue-in-cheek (and beautifully sketched) drawings of penises in various heroic scenarios (a penile depiction of Saint Sebastian riddled with arrows is a standout). As her emphatic postscript explains: “As a young painter I imagined that the quality of my work would exempt me from the prejudice and constriction suffered by earlier generations of women artists. It did not. In 1982 I gathered statistics comparing teaching positions, reviews, and exhibitions of women and men in Boston. They were unequal. I thought about that until it seemed funny.”

Enter Anna, who spent this past summer as an intern in the MFA’s contemporary department researching for a project on women, art, and age—a topic in which she had her own prior interest and expertise. Michelle shared The Book of Penis!, which Anna loved and which left her deeply curious about Jo Ann’s style, the words she used to describe her process, and connections between her art making and her life. And so a plan was hatched to pitch an interview to Boston Art Review together. The conversation below was an opportunity to listen to an artist whose work we admire and an act of solidarity among three women who, while at different life stages, share a strong commitment to questioning art-world cultures.

This conversation has been edited and condensed.

Jo Ann Rothschild in her studio.

MICHELLE MILLAR FISHER: We wanted to start with The Book of Penis!, which we love—it’s irreverent and wonderful, but it’s also a deep meditation on experiences in the art world that resonate with other people who’ve experienced misogyny. Could you describe making it and your motivations for bringing it into the world?

JO ANN ROTHSCHILD: I had published some very serious statistical comparisons about what happened to men and what happened to women artists [in terms of success in the art world]. I watched my male graduate school colleagues shooting ahead. I even had exhibitions in the same buildings as them, and mine would not get reviewed. I was so angry when I was writing this that I missed a stoplight. (I was okay; the car was a little scratched.) I was so naive—I thought, Well, people will see [these statistics] and this will change because it’s not right. A couple of years passed and nothing changed. I thought about it and it just started to seem very funny. I grew up around the University of Chicago, which meant I was around a lot of arrogant academics. I think my experience with them informed the book. The exclamation point [in the title] was really important, and I discovered while drawing that the placement of the images on the page is very important too. I drew the book in 1989, and it took until 2009 for it to be published. Even feminist presses found it just too something; I’m not sure what.

MMF: The way you’ve had to re-excavate this set of concerns fits with this issue’s “Emerge” theme. I think we’ve all had that feeling when the penny drops about pervasive misogyny at work and you realize how many other people have spoken up before you and that nothing has changed. It seems like a theme that needs to continually reemerge.

JAR: There are two things I want to mention. One is that we did sell out the first edition, and the second is that I’m going to publish—by myself—another edition because I am seventy-six and it took me twenty years to get it published the first time. One of the propelling incidents was that the ICA, after having shown women, suddenly when it was my generation had two shows in a row of essentially the same artists, and they were almost entirely men. There was outrage in the city. We had a meeting with the head of the museum, David Ross. I remember him saying, “I know you’re bothered that there aren’t women here. I have two daughters. I don’t like to think of myself as a misogynist, but what really disturbs me is that there aren’t enough Black artists in there.” By pitting two aggrieved groups against each other, it was as if only one of these could be represented.

Pages from The Book of Penis! by Jo Ann Rothschild.

ANNA NASI: I wanted to ask about your relationship with the art world today. What do you think of the subject matter of younger generations who are producing art versus that of your peers who are later in their careers? If someone were to make something similar to The Book of Penis!, for example, how would it be different today?

JAR: I don’t know because I’m not your generation. From the outside, it seems as if it’s a little more okay to talk about this stuff. There’s a way in which The Book of Penis! is very tasteful, and I think you guys could probably get away with it not being so tasteful; that’s my guess. But that’s also part of what makes the book funny.

AN: You’ve talked in previous interviews about coming to Boston before there was a solid contemporary art scene here and the challenges that brought for you. I’m curious about how that’s changed and what still needs to be done in Boston specifically to uplift female artists.

JAR: I made my peace with that by being very private. When I came to Boston, the Boston Expressionists were very defensive, and they were not happy about the idea of abstraction in general. I moved here from Chicago and Bennington, and both of them were more inclusive. I could not believe that we were having a discussion out of the nineteenth century. It was a very male environment with the exception of Kathy Porter, who was a really wonderful artist. There were very few women who were given any purchase.

MMF: Yesterday, we went to see the work of Jo Sandman [a Boston-based artist of Jo Ann’s generation], and the curator, Katherine French, who’s been helping Jo shepherd her work, said that Jo remained somewhat private because having to fight against the prevailing ethos of deep machismo in the painting world in Boston would’ve taken all the energy she would otherwise have devoted to art making—and she had a finite amount of energy, so she chose to make art.

JAR: We knew each other, not well, but in the Boston Visual Artists Union, which was a very important place for meeting other artists. Jo was more visible than most women were.

MMF: Katherine mentioned the Boston Visual Artists Union as deeply important. Can you talk about how that played a role in your own development as an artist?

JAR: It was a way to meet other artists. I met other artists in two ways—there and also because I’m a printmaker, and printing is such a collegial thing. I think the most important thing we did was go out for beers after the meetings. But it also gave me an understanding that in some countries, artists are actually supported, and that we did have economic interests in common—the fact that nobody had health insurance. We knew that housing and studios were precarious. The 300 Summer Street building and also the building in Somerville, Brickbottom, came about as a result of the work of the BVAU.

AN: I make art and was curious: When you describe your process, you talk about movement instead of thinking about the form being still. I’m wondering how thinking about an object in motion affects your actual mark making.

Canvases and works in progress line the walls of Jo Ann Rothschild’s studio.

JAR: I think of mark making a lot as it relates to music. When I was just starting out, I was at the Art Institute of Chicago for a year, and I had this great teacher named Ray Yoshida, who just said one thing to me. In one of my earliest classes with him, I started painting my paint box because I didn’t know what else to paint, and he said, “You’re not very interested in that, are you?” And I said, “No.” And he said, “But you are interested in the marks you’re making.” It gave me the freedom to just make marks. As students, we were given entrance to rehearsals of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and Georg Solti was the conductor. As I listened, I thought that the staff is very much like a grid. It’s a way of placing notes in time, and my work is a way

of placing marks in space. I thought a lot about rhythm—that was really the beginning of my grownup work. I don’t know if it was before or after that I was in Wisconsin and some deer were running across a field, and I just marked the rhythm of their flight. It was a doe and two fawns. It became my first etching.

MMF: There’s an art-world apparatus of external validation and gallery structures, but there’s also the deeply proximal relationship that’s felt when you have an amazing teacher. You mentioned Ray Yoshida—could you talk about how teachers have impacted your practice and personhood?

JAR: The teachers I loved growing up gave me a sense of a different way of being from whatever was in my family, and that was wonderful. When I dropped out of Bennington at the beginning of my sophomore year, I had the phenomenal luck to land someplace where Leo Garel was a landscape painter and watercolorist. I was determined to be a painter and subscribed to the idea that if you just kept at it, even if you were unhappy with it, that something would happen. I was the only one in the shop a lot of the time, and I was unsure. Garel gave me faith that if I was honest, I had the possibility of making a good painting.

Much more than learning how to paint, it was learning how to be. I went to the University of Chicago Lab School, which was a highly verbal place, and I could write with facility. One of the problems with my writing was that I was good enough to lie, and that wasn’t true of me as a painter. I wasn’t good enough to lie, and that’s one of the reasons I think I do what I do now.

AN: When I make art, I sometimes feel scared because I’ve always compared my own work to something that I perceive as “good” instead of letting myself enjoy the process. I’m curious how you have learned not to subscribe to visual norms imposed by others.

JAR: I had the good luck to grow up around the Art Institute of Chicago, and also my great aunt had an incredible collection of early-twentieth-century, mostly European work. I was an extraordinarily lonely kid, and the work really talked to me. I felt as if I had some internal understanding of it. I mean, you are who you are. You can’t paint like this or that other person.

AN: What work have you seen lately that’s speaking to you right now?

JAR: For a long time, I guess since 2015, I’ve been obsessed with Rembrandt’s portrait of Margaretha de Geer, a woman of seventy-eight. It may be particularly interesting to me now because I’m seventy-six. What’s astonishing to me about Rembrandt is that he paints women with the same humanity that he approaches men. And then my friend Rigoberto Mena, a Cuban artist I met in 2000, also inspires me right now. About twenty years ago, at a period when abstract painting was seen as very conservative, I went to the galleries and saw nothing that nourished me. And then I went to this little gallery in Miami, and there was Rigoberto’s work and there was Rigoberto himself. I made him show me everything that he had with him. And then he came to my studio and said, “This is my church.” He invited me to Cuba, and we’ve been friends ever since. One of the things we share is a love of line. And we both care a lot about touch.

Rothschild is revisiting a painting she originally conceived of in 1973.

AN: And what are you working on now?

JAR: I’ve been working on a big unstretched canvas that is the continuation of an idea I had in 1973. For years, I didn’t know how to make it happen. I kept a half-finished oil painting that was huge. And finally, I threw it out. I’m interested in regularity being interrupted by irregularity, and one of the shapes I’d thought about was a pinwheel coming together in the center with alternating colors. I tried it in oil—it was a mess. Recently, I made an eight-foot square and found the center with a chalk line and divided those quadrants in two and then felt free to improvise in a way that I hadn’t when I was younger. It was just fun to work on. Still, as I was fifty years ago, I was interested in the limits of vision in terms of what you can see, one black to another and one white to another.

Jo Ann Rothschild in her studio.

MMF: What made you come back to an idea from 1973? You woke up one day and thought, Wait a second, I want to come back to that particular thing?

JAR: When I was young, I used to think, What painter am I? I do this, I do that, I do this other thing. How can it all possibly fit together? But even now I find myself coming back to things that interested me when I was young. They’re still interesting to me. Jorie Graham, the poet, talked about being young and wanting to do work that will sustain you later. You want to gain skills that you may not use right away. I was lucky. That happened for me, and they’re what I return to now, over and again.