I first met Kristen Emack while volunteering at the grade school where my child was a classmate of her daughter and Emack was (and is) the parent liaison. I noticed that kids were always finding a way to detour from their destination to dart into her office to hug her. We’d be packing bags with food for kids to take home on the weekend, and she’d be handing one kid warmer winter boots, finding services for a family displaced by a fire, ordering supplies for a big event. She is the heart of the school.

Some days, if we’d both finished our tasks at lunch time, she’d place a stack of her photos she’d printed of her daughter and nieces on the table, and we’d punch straws into extra juice boxes and discuss them. Her empathy, tenderness, and eye for narrative composition were striking. Emack is keenly observant and able to distill complicated concepts visually. Her formal grace with her work is completive and moves it out of the chaos and sweetness often associated with the family journalism category and more into documentary photography.

Her work, primarily her photographic series called Cousins, a thirteen-year documentation of her daughter and nieces, has won numerous exhibitions and accolades and been shown around the globe. Emack makes it clear that while images of Black people, and particularly children, remain under-embraced, under-exhibited, and under-published, and thus undervalued, her motivation was not to specifically address race. Her work doesn’t set out to challenge stereotypes, but she hopes it disarms any implicit bias non-Black viewers may have when they view it. In a similar vein, the series naturally steps away from the oft-prescribed narrative that girls start out innocent and get distant or preoccupied as they get older because their interests digress into individuation or dating. The images focus on the girls’ relationship to themselves and one another.

Fast forward to today, and we have kids in high school, while one of her nieces has gone to college (to become a photographer). Emack is a 2022 Guggenheim Fellow, a MacDowell Fellow, a Mass Cultural Council Fellow, and a St. Botolph Emerging Artist Award recipient. Many Guggenheim Fellows are ensconced at a university that affords them a sabbatical to focus on their work, but Emack, this humble and mostly self-taught talent, continues serving her community at the school. She spent her fellowship year powering through her all-consuming job and single-parenting while beginning new work related to gentrification in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and focusing on getting Cousins into its new form—the series has just been published in Italy by L’Artiere Edizioni as a compact book meant to evoke the intimacy of a journal.

The following conversation has been edited and condensed.

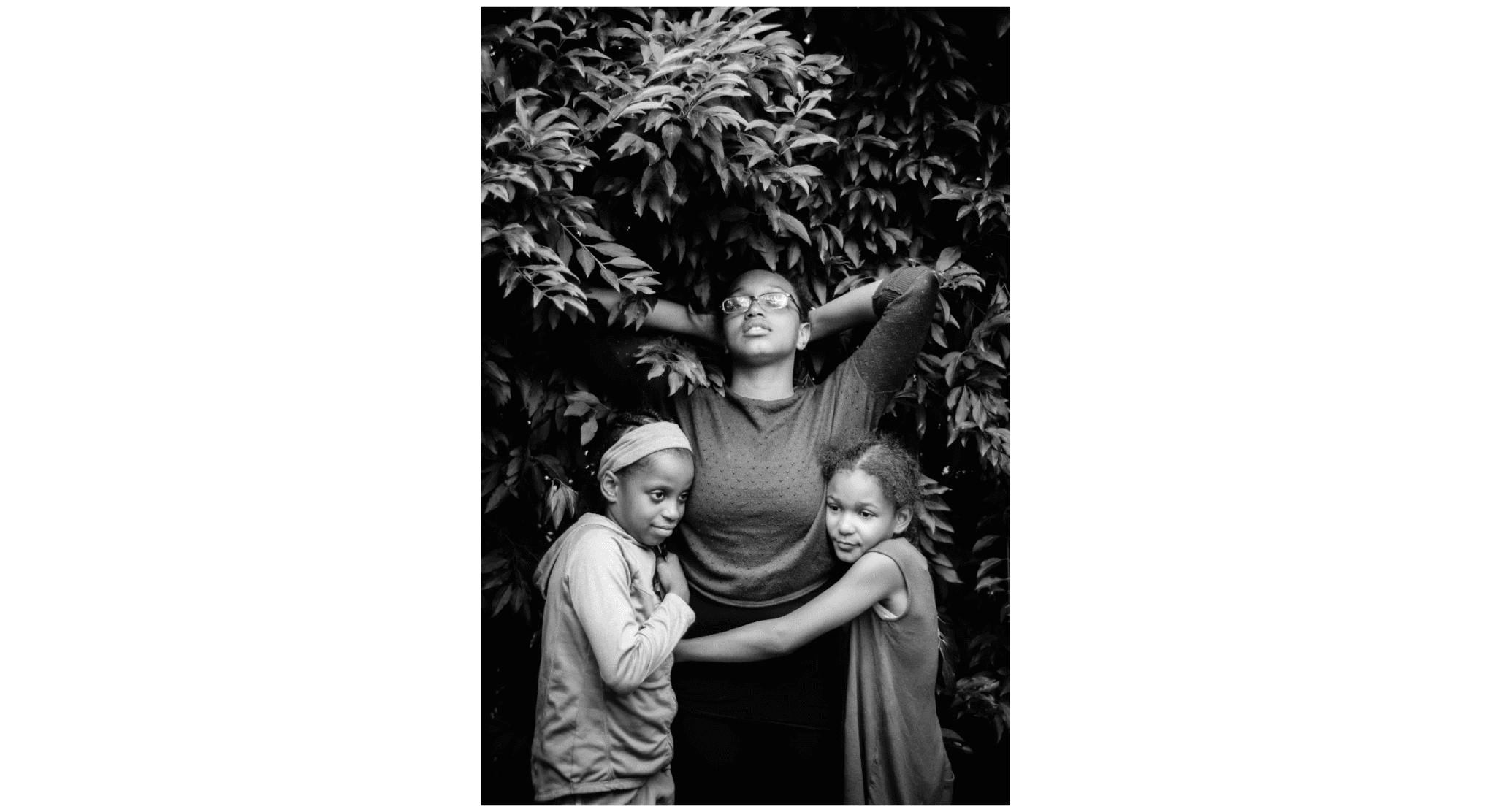

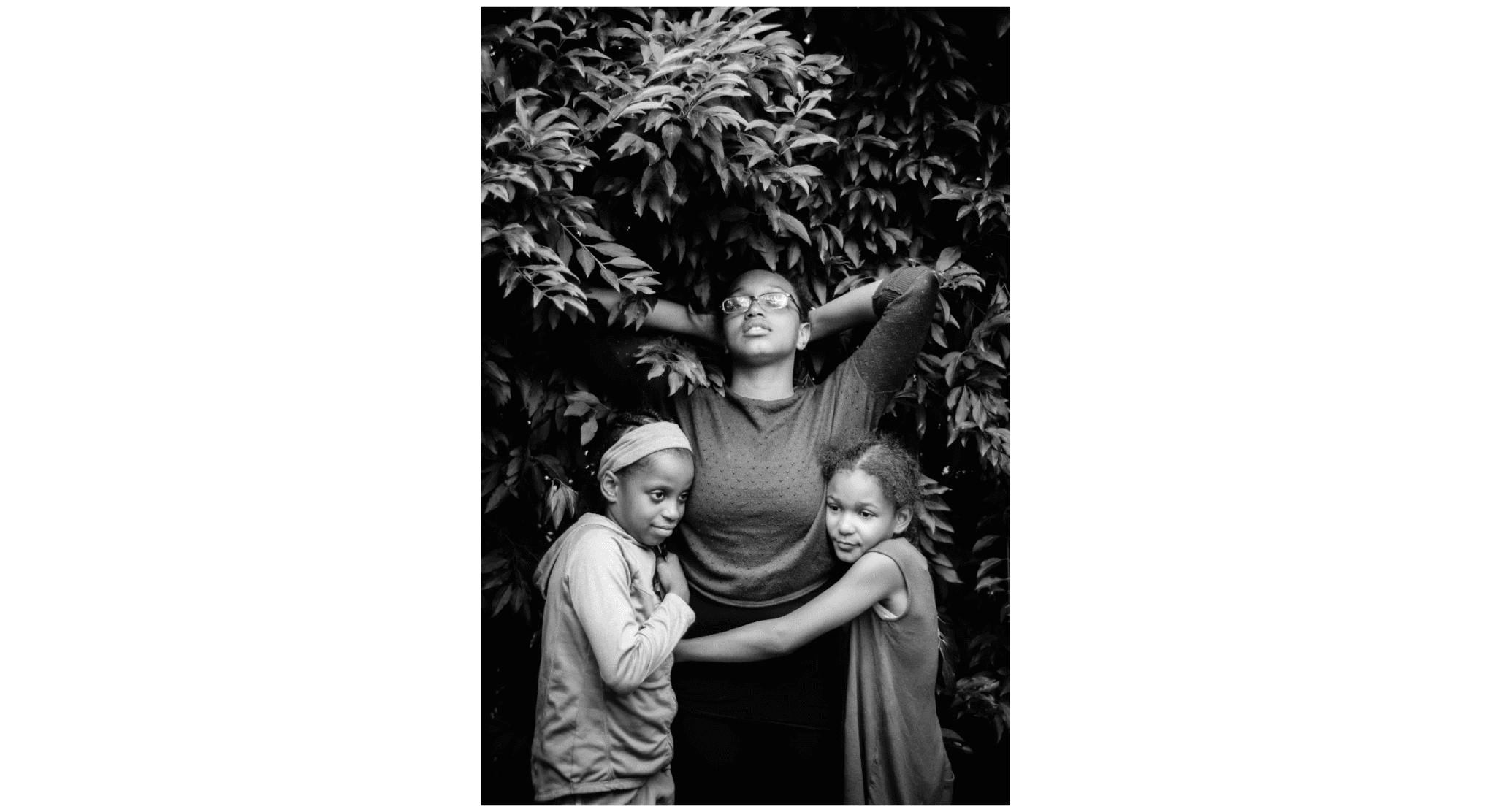

Kristen Emack, Touch, Killingworth, CT, 2015. Cousins series. 1/10 40” x 26” inkjet print. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Bethany Ericson: First, wow, congratulations on the Guggenheim and the book—that is exciting! Tell me about this journey. How did your photography of the kids become a series?

Kristen Emack: I didn’t decide to do it. It evolved out of impulse and intuitive feeling. Sometimes I was probably responding to discomfort in myself by engaging with my surroundings. Cousins was originally me taking pictures of my daughter and nieces in Cambridge, or together on family trips. It wasn’t until I took Touch, a picture of two of the girls in conversation in a body of water with their fingertips touching, in my hometown one summer that I saw it. Partly maybe because it was so different from my experience, not having grown up with that kind of family experience in that place.

BE: I remember that one—the kids in a pond in sagging bathing suits, leaning on each other, talking. One has that incredulous but adoring look of innocence.

KE: Yes, when I was editing it, I realized there was something more to the images I was taking than well-composed pics of some of the kids in my family. I was seeing more universal themes of childhood, femininity, memory, and at some point, I became more intentional about the photos and how often I took them. It entered into our time together in a more deliberate way and evolved into a series.

BE: How did that change things? Did the pictures become more posed?

KE: In the beginning, the girls didn’t pay much attention to me; I just took pictures casually and didn’t ask much. The images were more observational—as loving family members, they were used to being in close proximity and to me with a camera. It was an extension of our time together. As they aged, it changed some. They didn’t become resentful, or posed, but in the later images they knew the pictures could be shared with a wider audience, and they had more self-agency in the photos. You can see in the series how they start to present themselves with confidence. But even those later images were never staged. As the series grew, there might be moments where I’d give the smallest directions, like “Hey, hold that.” I wasn’t setting things up but might, say, require a pause.

BE: Once you thought of it as a series, did the emotions or themes you were identifying begin to teach you things?

KE: Yes. When you work on a project for a long period of time, you can constantly reflect on why it is important and why it still has momentum. I was not so connected to my family and my cousins were older; I didn’t know them well. Being an aunt and a mother allowed me to learn about family, see what it could mean to be a cousin. I was enthralled how the girls would gravitate toward each other.

BE: I really feel that comes through.

KE: Yeah, because they knew they would always be in each other’s lives. They simply expect and know that they would spend important rites of passage and holidays with each other. It was a marvel to observe how they were accepting and anticipating each other’s presence all the time. They were each other’s first friends.

Even though I’d had a kid before my daughter, he’s the first grandchild on both sides of the family and the second cousin didn’t come around for a long time, so like me, he didn’t have that cousin relationship as a kid.

Kristen Emack, Forsythia, Cambridge, 2017. Cousins series. Inkjet print. Photo courtesy of the artist.

BE: You’ve described the moments you have captured as being sacred. Is the sort of quietness of your photos related to that idea that they were taken with a “maternal gaze”?

KE: Yes and no. I wouldn’t say that exactly, because that term is typically used with a different genre of family photography and I may be addressing larger responses to the idea of femininity than are typical to that genre.

We often talk about the “female gaze” to the point where I believe it is misused or misunderstood. I think that concept is still very rooted in the patriarchy. Cousins is, of course, a female body of work because I am female, turning my lens on four younger females, who look back at me. But their gaze is about agency and self-making and connectedness to one another.

The sacredness—that is me tapping into moments of reverence, including reverence for the girls, since they’re experiencing a trusting adult relationship with me. And I’m focusing on moments when there is reverence for each other and ourselves. While I think a quality of my photos is that I am not really a presence in them; at the same time maybe in a sense I am there, in that I’m always using photos to connect—I aim for that reverence that an open heart feels with the energies of the universe. Basically, that sort of quietness of my work is that reverence.

BE: That’s beautiful, kind of a flow state.

KE: Something important to know about Cousins is that although it documents the lives of four girls of color growing up together over time, I never set out to make a political body of work. I don’t think it’s up to me, a white photographer, to presume to tell the story of Black childhood, even if I am photographing my own child and nieces. Over time, though, through multiple conversations about racism and identity, the girls, particularly the oldest three, had their own realizations about representation. Leyah and Apple, both sixteen now, reflected that the publication of Cousins could help people “become more educated about representation.” And back in 2021, when I mentioned to Kayla, the oldest of my nieces, that I was considering ending the series before she went off to college, she quietly told me “If Cousins stops, I feel like then I stop too.” Having a visual presence in the world did become important to them.

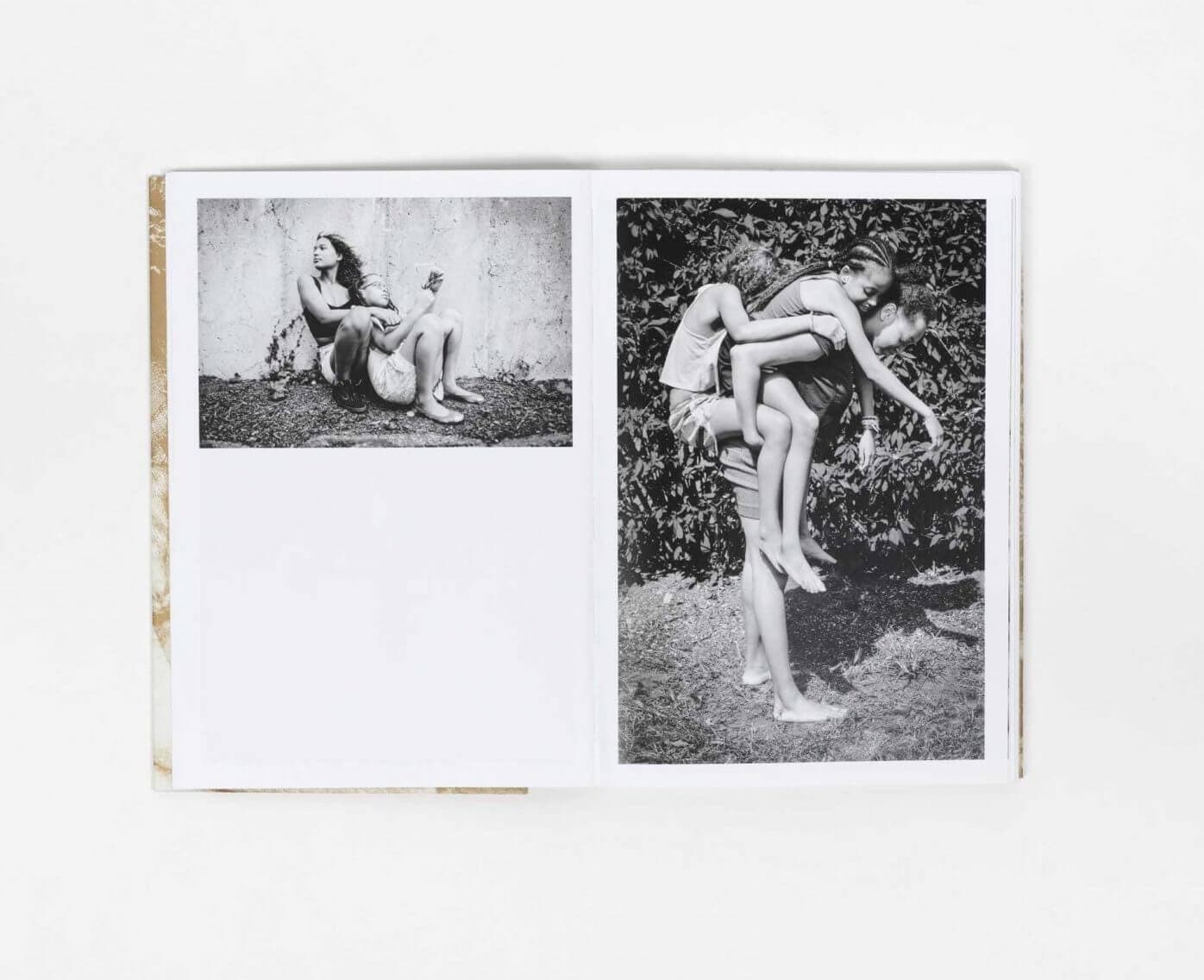

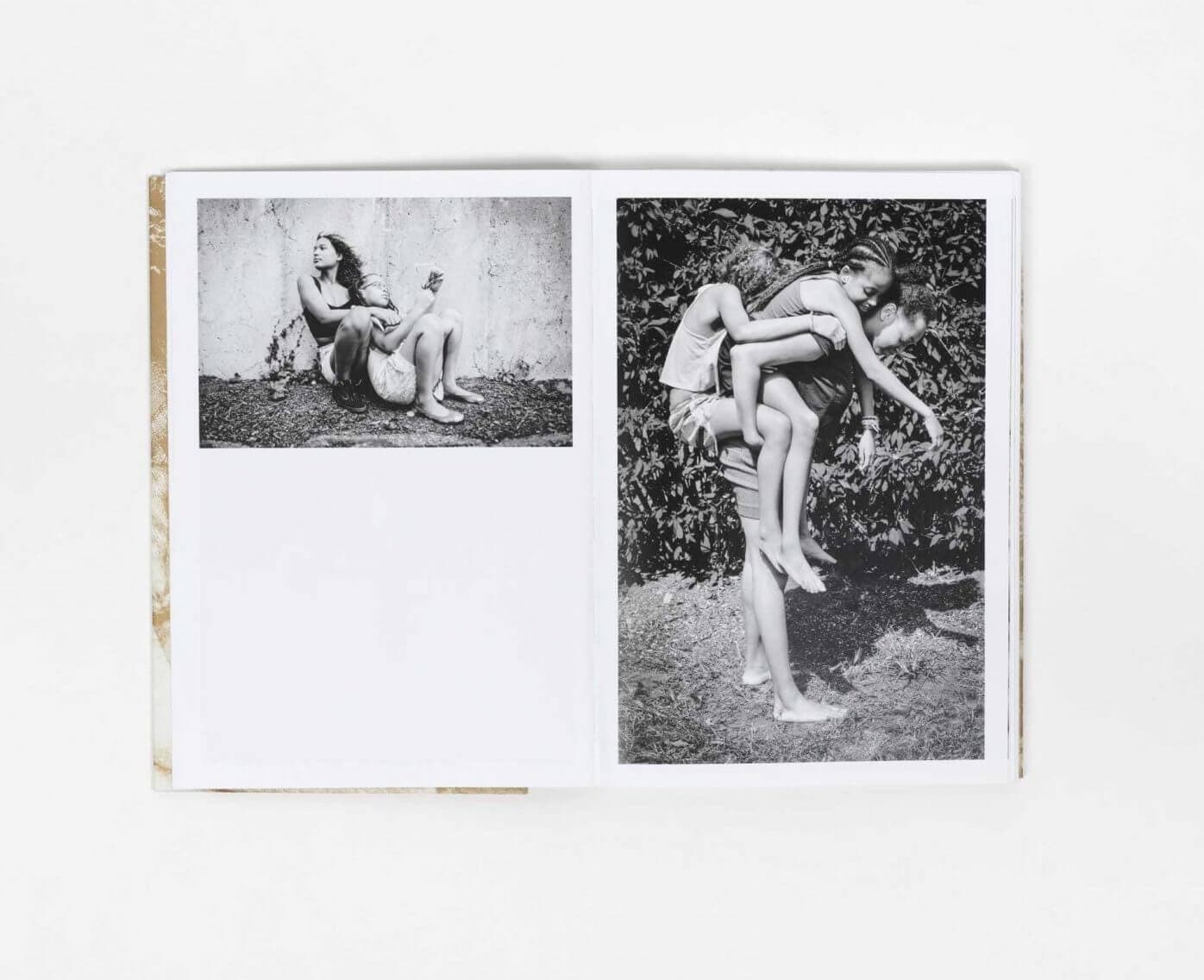

Interior view of Kristen Emack’s book, Cousins, published by L’Artiere Edizioni, 2023.

BE: Did winning a Guggenheim change things for you?

KE: It is obviously thought of as a prestigious fellowship. I think what’s less obvious is the community of it—like once a fellow, you are always a fellow. And it is a relief that it doesn’t become irrelevant after a year! This community is a big gift, similar to what I found attending MacDowell. It shaped my experiences—who I can connect with and learn from. And the whole thing was less intimidating than I expected. I don’t have the typical trajectory of an artist’s career with an MFA, but I didn’t turn out to be as much of an outlier as I thought, and everyone administering the Guggenheim has been so warm and thoughtful and supportive.

I work in a different type of learning environment and can’t take a sabbatical like many fellows, but it has given me some breathing room. I can do things like purchase those frames I need, or send work to a gallery across the country. I can buy gear that allows me to do my job smarter instead of harder. It’s given me that kind of access: I can communicate my ideas more clearly because I have access to better equipment, and the credential is helpful as something I can lead with when networking and meeting people. They are more likely to pay attention, take me seriously. It allows people to trust that I am making impactful, important work, I don’t have to convince them of that to begin a relationship with them.

Kristen Emack, Bird House, Cambridge, 2023. Inkjet print. Photo courtesy of the artist.

BE: So, what’s left for this series, and what’s next?

KE: Cousins was just in a solo show at Blue Sky Gallery, in Portland, Oregon, and then the book was released at the International Center for Photography in New York in April. It’s beginning its rounds at international photo book and photography fairs, including Paris Photo next November. Cousins is being exhibited in Belfast, Ireland, this summer as one of five winning photographers in the Belfast Photo Fest. And I have a lecture and exhibition at the Cambridge Public Library in September with a book signing.

Meanwhile, I am working with a new desire to document, to archive, who is injured in my city of Cambridge as it undergoes extensive gentrification. Cambridge is finding its new cultural norms and demographics as it becomes an “Innovation City,” and I’m working with some ideas that are still forming about who may not be here in twenty years. We’re familiar with the term “education gap” or “achievement gap,” but there are invisible gaps I would like to explore, photograph, and write about that people who have not experienced them don’t see as their neighbors are navigating all these things.

BE: Kristen, what a pleasure, thank you. Where can people find your book?

KE: It is for sale on the publisher’s site, lartiere.com and can be purchased directly from me at kjoynikoapple@gmail.com.