Oh, 2021—the year we thought must certainly be better or different than the one prior. Though many of the things we had hoped would remain in 2020 did follow us into this year, there were moments of respite provided by the reopening of physical spaces for art. Here, members of our editorial team share favorite moments spent back inside museums, the joy of catching public art in our neighborhoods, and the artists whose gallery presentations stuck with us.

Best of Gallery Hopping: Kim Faler at LaMontagne Gallery, Autumn Wallace at Gaa Gallery, and Catalina Schliebener at Boston Center for the Arts

By Leah Triplett Harrington

Gallery hopping in 2021 felt like a revelation. After a year-plus of online viewing, I felt affirmed in what I’ve always thought: There’s just nothing like seeing artwork in person! Kim Faler’s hypnotic “Something That Feels Like Truth,” on view in April at LaMontagne Gallery, insisted this for me. Somehow both playful and grave, Faler’s absorbingly tactile show avowed the roller coaster of human experience.

Autumn Wallace, “How to Hug Yourself: 10 Steps (With Pictures),” installation view, May 14 — June 28, 2021. Photo courtesy of GAA Gallery, Provincetown.

Then in June, I was lucky enough to be in Provincetown to see Autumn Wallace’s show-stopping “How to Hug Yourself: 10 Steps (with Pictures)” at Gaa Gallery. At turns sharply precise or elusively abstract, Wallace’s paintings and sculptures are little kaleidoscopes, undulating color, shape, and texture. Their compositions (in both 2D and 3D) accrue stuff from everyday life to create captivating remixes of the familiar. Like Faler, Wallace resolutely considers the confusion and exuberance of living in a human body.

Catalina Schliebener’s work hits this same note, but in a much different tone. I’m still thinking about their exhibition “Growing Sideways” at the BCA this fall, in which they painted the cavernous Mills Gallery a lush, blush pink. Punctuating the space were sculptures created through the accumulation of familiar childhood items placed directly on the ground. Most striking was a low plinth covered in hundreds of pink pencil erasers, the kind that you put on top of the pencil after the original one has been rubbed away. All three of these artists use the gathering of “common” found materials to unsettle the familiar. As in Schliebener’s “Growing Sideways,” erasing figured prominently in Faler’s “Something that Feels Like Truth.” Gathering together and erasing to start fresh both seem like optimistic gestures in this moment, and I’ll take that hope with me to 2022. Even if we go back to the online viewing room.

Exhibitions on Evocations of Memory and Place: “Home Cooking,” “The End of Susan, The End of Everything,” and “Combahee Conversations”

By Jameson Johnson

Stephanie H Shih, Pearl River Bridge Superior Light Soy Sauce (China), 2021. Photo courtesy the artist and LaiSun Keane Gallery.

At the newcomer SoWa gallery LaiSun Keane, a rigorous lineup of exhibitions featuring local and international artists has kept me returning time and time again. But this past fall, “Home Cooking,” curated by critic and poet John Yau, captivated the senses. Here, he presented work by eleven Asian and Asian American artists centered on food and the nostalgia or memories often associated with a particular dish, ingredient, or occasion. Stephanie Shih’s ceramic condiment jars depict versions of soy sauce from China, the Philippines, and Indonesia with the bespoke touch of the artist’s hand contrasting the mass production of these household ingredients. Meanwhile, Charles Yuen’s Tea Dream offers an absurd and serene portrayal of a looming tea kettle. Ranging from ubiquitous to personal, these studies on food invite everyone to the table. For Yau, who was born to Chinese parents in Boston but has spent most of his adult life in New York City, the exhibition was something of a celebratory homecoming and a direct response to the increase in hateful acts perpetrated against Asian Americans after COVID-19 made its way to the US. To accompany the exhibition, Yau penned an essay on how meditations on food can invoke a “Proustian moment.” If you missed the exhibition, tune into the gallery talk, where Yau delves into his own interests in food, writing, memory, and community.

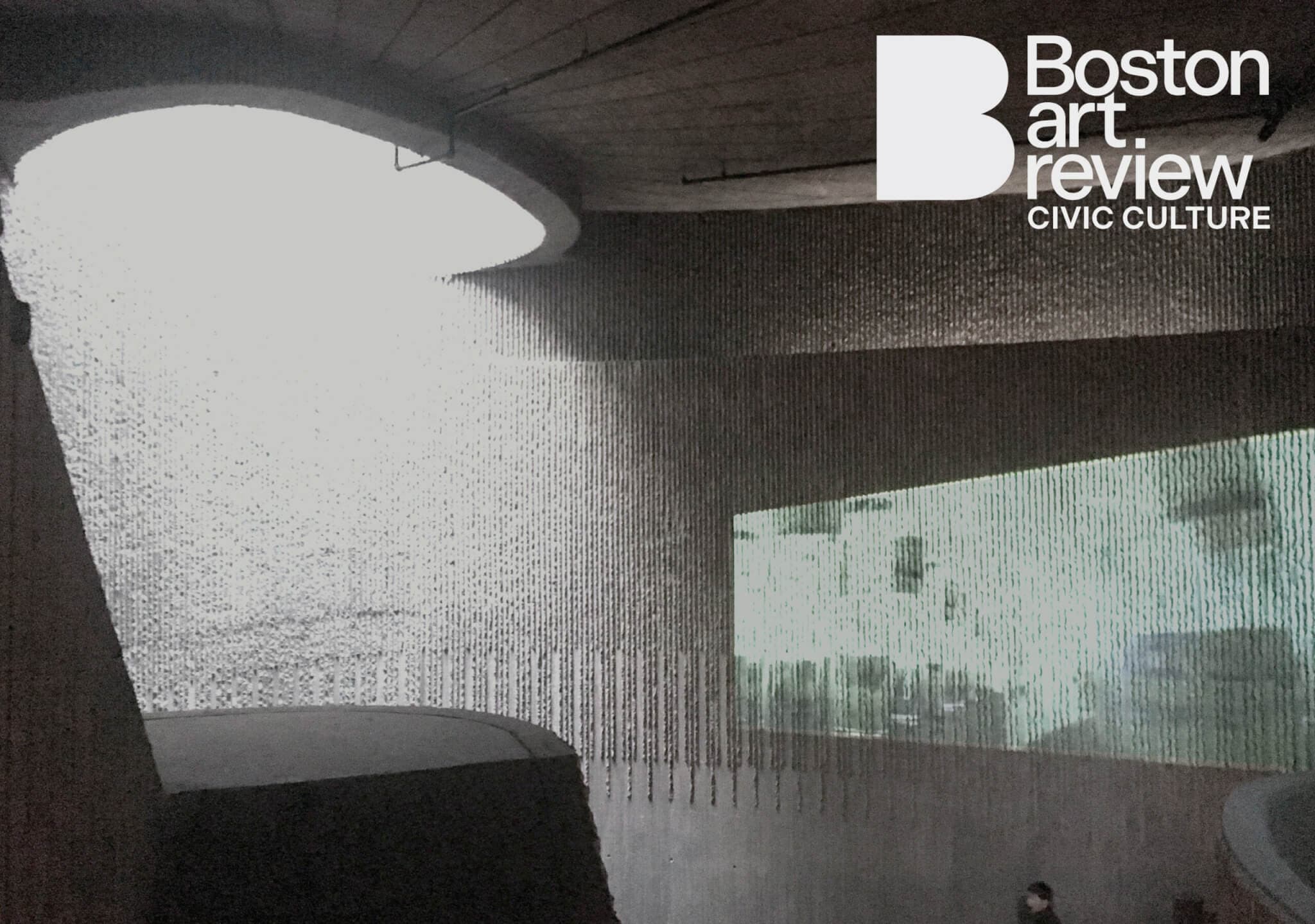

Dell Marie Hamilton, “The End of Susan, The End of Everything,” installation view, James and Audrey Foster Prize September 1 — January 30, 2021. Photo by Mel Taing, courtesy Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston.

At the ICA, Dell Marie Hamilton’s Foster Prize exhibition considers memory and legacy through the personal effects of Susan A. Denker, a beloved professor, archivist, and community leader who passed suddenly in 2016 and left many of her belongings to Hamilton. Hamilton became Denker’s mentee and friend after taking her class at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, where they connected over a shared love of Black visual artists. After years of holding onto the objects, some gentle coaxing from curator Jeff De Blois led Hamilton to begin sorting through the dozens of boxes filled with treasured books, albums, art, and oddities accumulated over a lifetime: original Combahee River Collective texts, a Sylvia Plath first edition, a peculiar 1960s game meant to illuminate the injustices Black Americans faced. For “The End of Susan, The End of Everything,” Hamilton recreated a version of Denker’s Cambridge apartment. In each section of the “house,” she intersperses her own artmaking (video performance pieces) and curatorial practice (careful additions of texts, photography, and her own family history). In doing so, Hamilton places her voice in dialogue with renowned artists, writers, and thinkers who made their way to Denker’s shelves.

Nearly two years into a pandemic defined by loss, this interpretation of a life through the objects left behind is a poignant consideration of how we make meaning, ascribe value, learn, and love. My only gripe? Flipping through the trove of books, letters, and photographs is strictly off limits.

Back in the virtual realm, the Combahee Conversations organized by Arielle Gray, Cierra Peters, and Jen Mergel alongside the “Combahee’s Radical Call” exhibition at the BCA brought together a brilliant lineup of artists and thinkers for extended conversations around topics of Black Feminisms, intergenerational connection, tenderness toward the land, and creative growth. I hope these moments for communal gathering, growth, and sharing are carried into future seasons.

On Whimsy and Encouragement: Samantha Nye and Andy Li

By Kaitlyn Clark

It’s hard not to talk about “the return” to the art world in 2021. Andy Li’s foray into public art, The Herd, commissioned by the Greenway and installed in Chinatown, marks just that. The work opened with the Chinese New Year, and 2021 was the year of the Ox. The installation consisted of two groups of banners; one read “IF THERE’S A WILL THERE’S A WAY” and the other read “KEEP DOING WHAT YOU DO.” These phrases of encouragement and the metaphor of the Ox as a herd animal work together to give us that push as we keep going.

“Samantha Nye: My Heart’s in a Whirl,” installation view, Lizbeth and George Krupp Gallery, 2021. Photo © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Meanwhile at the MFA, Samantha Nye’s solo exhibition “My Heart’s in a Whirl” was filled with care, joy, intimacy, and PINK! The whimsical installation featured soft pink carpet under your feet, shimmery pink tassels enveloping you, and a heart-shaped hot tub placed for seating. You can’t help but let your heart “whirl” while watching Nye’s queered versions of Scopitone videos originally from the 1950s and ’60s. It was my first time sitting in a hot tub to watch a video, but hopefully not my last.

An Ode to Murals: Amanda Hill, Erin Genia, Ponnapa Prakkamakul, and Silvia López Chavez

By Karolina Hac

Erin Genia, Wakpa, installed at Tufts University Art Gallery, Medford Campus, 2021. Photo by Jameson Johnson.

Having spent a lot of time outside this year, I was excited to see how many formerly bare walls around me became canvases for murals. Closest to my Medford home, I spotted Amanda Hill’s A Journey Through Medford (which took nearly three years of cutting through bureaucracy and COVID-related delays to complete) adding a little color to Haines Square. Nearby, Erin Genia’s Wakpa outside Tufts Art Galleries provides a visual and aural respite on campus. Both Genia and Hill reference the Mystic River, though with vastly different visual language. While Hill’s depiction focuses on our engagement with nature in a realistic and community-centered manner, Wakpa, which takes its title from the Dakota word for “river,” uses geometry (specifically the Morningstar) to present an Indigenous perspective on our connections to the land.

I also had a chance to dine out at Tambo 22, a cozy Peruvian restaurant in Chelsea, and I’ll admit I went in part to see Silvia López Chavez’s mural. The work celebrates “Peru’s cultural heritage, flora, and fauna” in her signature vibrant style, featuring a Peruvian woman flanked by a llama, an alpaca, and a cock-of-the-rock bird. On a late summer night, surrounded by string lights and music, the colors of the mural elevated the experience Chef Jose Duarte created.

Ponnapa Prakkamakul, Where We Belong (歸屬 歸宿) installed at 79 Essex in Boston’s Chinatown, 2021. Photo by Katy Roger courtesy of the artist.

And most recently, I stumbled across Ponnapa Prakkamakul’s playful composition Where We Belong in Chinatown at the former site of the Ho Toy Noodle Company on Essex Street. The 150-foot mural was created in collaboration with the Asian Community Development Corporation’s A-VOYCE youth program. There’s something magical about discovering these large-scale infusions of color and story in the built environment—I’ve long admired the way other cities teem with murals, promoting a sense of community and commitment to the arts. Here’s to more murals in 2022!

Bright Moments for Dull Times: Erin Loree, Katrina Sánchez, and James Clar

By Maya Rubio

Seeing “The Consistency of a Sunset” at Abigail Ogilvy was my first time visiting a gallery since the beginning of the pandemic, and the works by Toronto-based painter Erin Loree and Charlotte-based fiber artist Katrina Sánchez felt completely divine.

Installation view, “The Consistency of a Sunset,” Abigail Ogilvy Gallery, April 28 — June 6, 2021. Photo courtesy of Abigail Ogilvy Gallery.

Loree’s paintings are like a psychedelic night sky: electric-colored ombré sunsets, candy-colored stars, or sprinkles. The 3D texture of the paint oozes off the canvas, a celebration of the medium’s ability to move, vibrate, dance. I still think about the whipped dollop of sugary pink in Thought Bridges. The rainbow palette in Loree’s paintings partners with Katrina Sánchez’s fiber pieces, which likewise exemplify color’s ability to create a visceral reaction. Life Source, a floor-to-ceiling installation, was the star of the show. The interwoven rings of fuchsias, yellows, light blues, peaches, creams, reds, and browns concocted something like a playground slide from the heavens. Like Loree’s works, Sánchez’s fiber pieces also play with texture. The whole gallery feels dynamically alive in its vibrant color and movement, the hands and imaginations of the artists still present in the space.

James Clar, “Space Folding,” installation view, Praise Shadows Art Gallery, October 15 — November 14, 2021. Photo courtesy of the artist and Praise Shadows Art Gallery.

“Space Folding” at Praise Shadows was another special exhibition. James Clar works in digital media, light sculptures, and new technologies, and his Boston debut at Praise Shadows felt playful, clever, and new. Clar’s Freefall series uses colored LED lights to cast a portrait of a figure suspended in mid-air. How exciting to see art manifest between its materials—to try to hold the bleeding light, to know it. In Nobody’s Home, a generic wooden door looks like it leads into a conference room. Beneath the door, LED lights and accompanying shadows show footsteps passing. This work accesses some deep mystery—I even asked gallery attendants if I could open the door. I love art that sparks some true curiosity, prompting a need to ask someone, “What’s beyond?”

Kaitlyn Ovett Clark is managing editor for Boston Art Review and the exhibitions and public programs manager at the Tufts University Art Galleries at the SMFA.

Karolina Hac is an editor and development manager for Boston Art Review and head of marketing for Höweler+Yoon Architecture.

Leah Triplett Harrington is edtior-at-large for Boston Art Review and curator at Now + There.

Jameson Johnson is editor-in-chief at Boston Art Review and marketing and development manager at MIT List Visual Arts Center.

Maya Rubio is an editorial assistant at Boston Art Review.