The shell of the Watertown Arsenal campus still sits on the bank of the Charles River, twenty-five years after its closing as a military campus. While it no longer serves as a hub for military laboratories or weapons manufacturing, many of the original buildings still stand, transformed into office space, shops, restaurants, and parking. In its former life, the Arsenal was owned by the U.S. Army; established in 1816 and sold to be redeveloped for civilian use in 1995, it was an important manufacturer of weapons in the Civil War.

Chantal Zakari’s A Work in Progress, on view at SoWA’s Kingston Gallery, dives into the rich history of the Watertown Arsenal and pulls out interwoven layers that span immigrant experiences, architectural legacy, and military industrialization and experimentation. The exhibition reads like an architect’s exploration of a site, tracing the intersections of people and place from its inception to its reincarnation in the twenty-first century. In this exploration of a place that has been witness to many changes over the last 200 years, Zakari juxtaposes past and present to illustrate how American values have shifted.

Chantal Zakari, Building, 2020. Installation view. Image courtesy the artist and Kingston Gallery.

Zakari, who lives in Watertown, has created work about the town before, including Lockdown Archive, created after the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. In her exhibition statement, Zakari writes she became interested in the Arsenal “because of the many dichotomies it represents,” and researching the site reminded her of her childhood in Izmir, Turkey, where she grew up across from the NATO headquarters. Through the use of contemporary and archival materials, including photography, videos, and printed work, the past and present meet, overlapping, interrupting, and intertwining as if in a dance.

In the main room, the organizing principle is centered around layering. Zakari likens this effect to the act of researching and opening files on a computer, stacking one image on top of the next. Unlike a historian’s archive, Zakari’s use of fragmentation coaxes the viewer to peer closely, preventing the work from reading like a report. Rather, this exhibition is like an archive repurposed to convey a sense of place with an emphasis on the early-to-mid twentieth century. Through the use of propaganda posters, images of workers laboring over heavy machinery, and military portraits, viewers can briefly glimpse the evolving spirit of the complex without ever having stepped foot inside it.

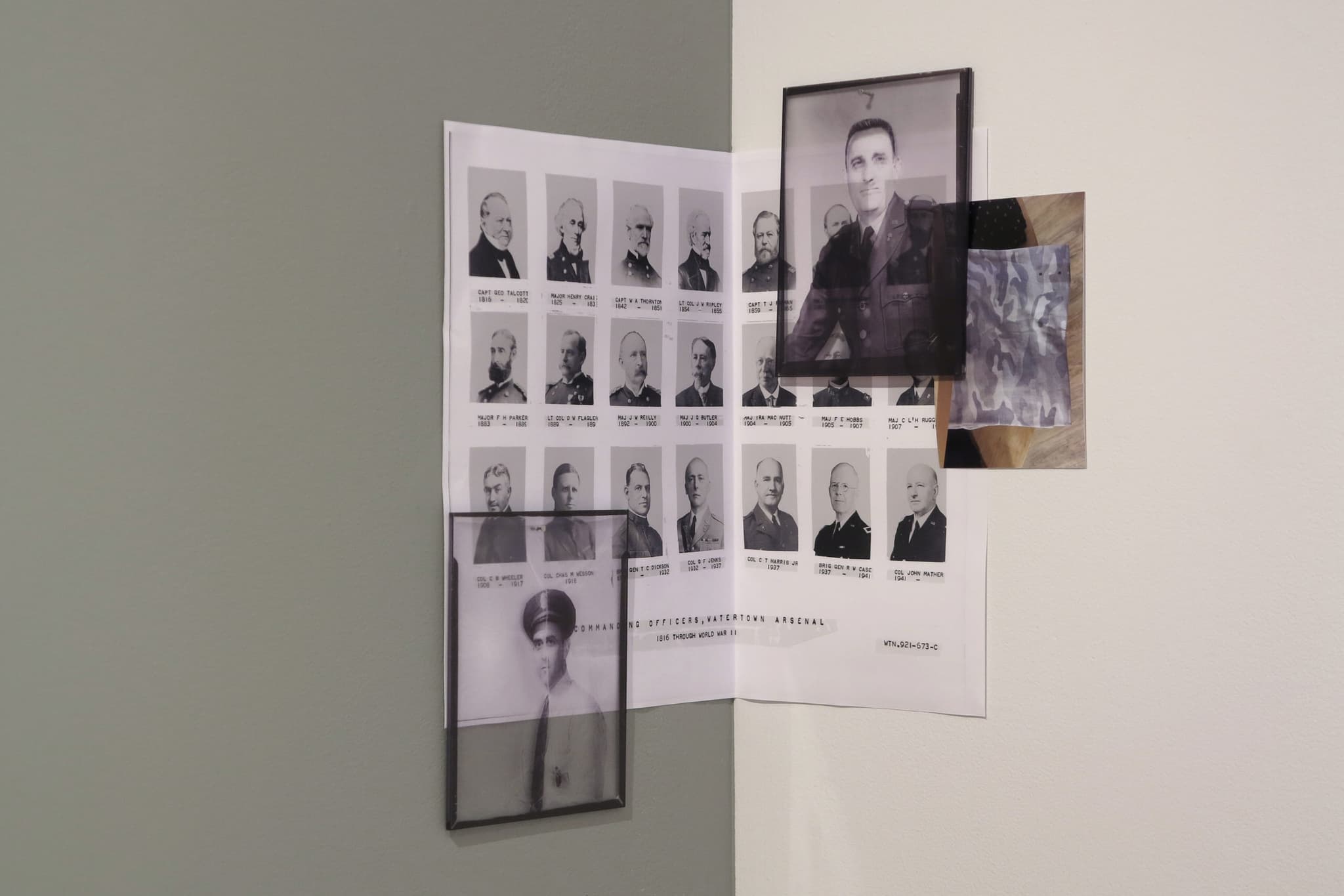

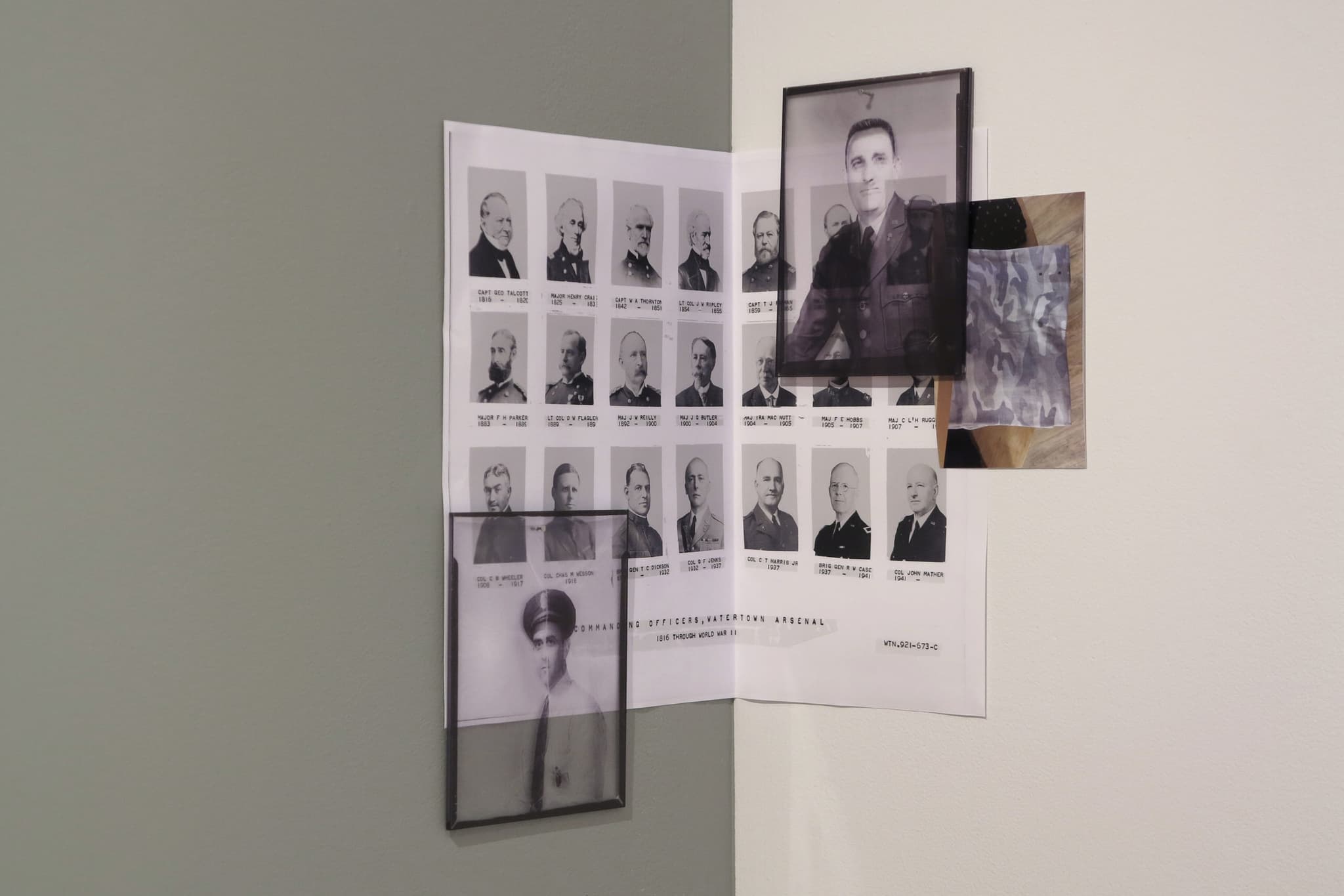

Chantal Zakari, Commanding Officers, 2020. Two loose prints with two photos printed on acrylic. Image courtesy the artist and Kingston Gallery.

Towards the back of the gallery, the sole sage green wall draws the eye toward a salon-style configuration of eight framed photographs titled Building. The work has an erratic rhythm; like other works in the room, it is a photomontage describing the story of the Arsenal’s primary use as a weapons manufacturing site, but interspersed among the archival material are photos of clothing and mannequins taken by Zakari. The artist playfully splits images between frames—in one instance an image of men in lab coats and masks handling a large canister is split into three frames. Tucked into the corner between this salon hang and the next, a montage of military portraits titled Commanding Officers is pinned to the wall, beckoning the viewer closer. Zakari plays with the cadence of the show throughout, using scale and fragmentation as her primary tools.

In About the Past, a two-screen video installation, the interaction between past and present is a literal dance—on one screen dancers Sofia Engelman and Em Papineau step and sway around the current-day Arsenal grounds, bringing life to corners of the site that have long been abandoned. The duo “[recreates] movements referencing the workers and officers that used to occupy the buildings,” as Zakari writes in her exhibition introduction. The voice of singer Ruth Harcovitz fills the small room, singing “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition” and “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy from Company D” while scenes of the site’s contemporary construction play on loop. As one watches Harcovitz perform in her wartime uniform between two women wearing face masks, and Engelman and Papineau dance, the site’s past seems so removed from our reality that it feels foreign.

Chantal Zakari, About the Past, 2020. Two-channel video installation, 13 minutes. Installation view. Image courtesy the artist and Kingston Gallery.

In the main gallery, copies of Arsenal News are available for visitors to take home. This newspaper, which is also available around Watertown Arsenal Yards, is Zakari’s reimagining of a now-defunct biweekly publication for the Arsenal workers. The artist’s version is not a summary of the exhibition, but within its twelve pages, she has curated a perspective that focuses on the people and their labor, tracing this thread through to the present day. The work is a pastiche of past and present, using historic and contemporary photos and clippings of people and events from the Arsenal’s history. Like the video installation, the two interrupt each other, and the line between which informs the other is blurred.

As Zakari blends an academic’s rigorous research with an artist’s interpretation of a place, she calls forward ghosts of both people and place. Faces of workers and military leaders peer at viewers from seemingly every corner, reminding us of the complicated history of a place like the Watertown Arsenal. While including more of the site’s history prior to the nineteenth century would have made for a complicated but perhaps more complete visual, the artist’s narrowed focus strengthens the dualities presented.

Zakari writes in her introduction to the exhibition that its title refers to the “continuous transformation of this space.” In a way, this site has not only been witness to major events in American history, but has also been rebuilt according to societal needs and values. One of the remaining reminders of the site’s history is the shell of the Army buildings. As Zakari explains in “Arsenal News” and in her statement, the Arsenal was “placed on the deferral Superfund list of toxic waste sites,” which means the buildings could not be demolished completely and turned into the quintessential American mall. As world wars ended and consumerism slowly subsumed wartime industrialization, the dichotomy between the two still remains embedded within the site, which comes to life through Zakari’s eye.

“Arsenal News,” 2020. Newsprint, edition of 350. “Arsenal News” is also distributed at the Arsenal Mall, Arsenal Yards, and various locations in Watertown.

A Work in Progress is on view at Kingston Gallery, 450 Harrison Ave #43, Boston, MA 02118, through December 6, 2020.