As we arrived at the scaffolded exterior of the National Center of Afro-American Artists (NCAAA), John Wilson’s Eternal Presence sculpture—a seven-foot-tall countenance Wilson likened to “a symbolic black presence infused with a sense of universal humanity”—witnessed our entrance. We were here to speak with Edmund Barry Gaither, the storied curator, scholar, and organizer. He has been the director and curator of NCAAA since its inception in 1969, having worked alongside founder Elma Lewis. Gaither’s dedication to supporting Black artists and sustaining Black art and culture in Boston brought us to this sit-down with Danny Rivera, a young vocalist and arts advocate, who—much like Gaither—cares foremost about uplifting the artist’s voice.

Gaither, raised in South Carolina and educated at Morehouse College, arrived in New England to pursue an MFA in art history at Brown University before becoming a curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1969. He came to the NCAAA in the same year and has since overseen hundreds of exhibitions, built out the museum’s collection to over 3,000 objects, and traveled the world conducting research, planning conferences, and teaching coursework on African American arts.

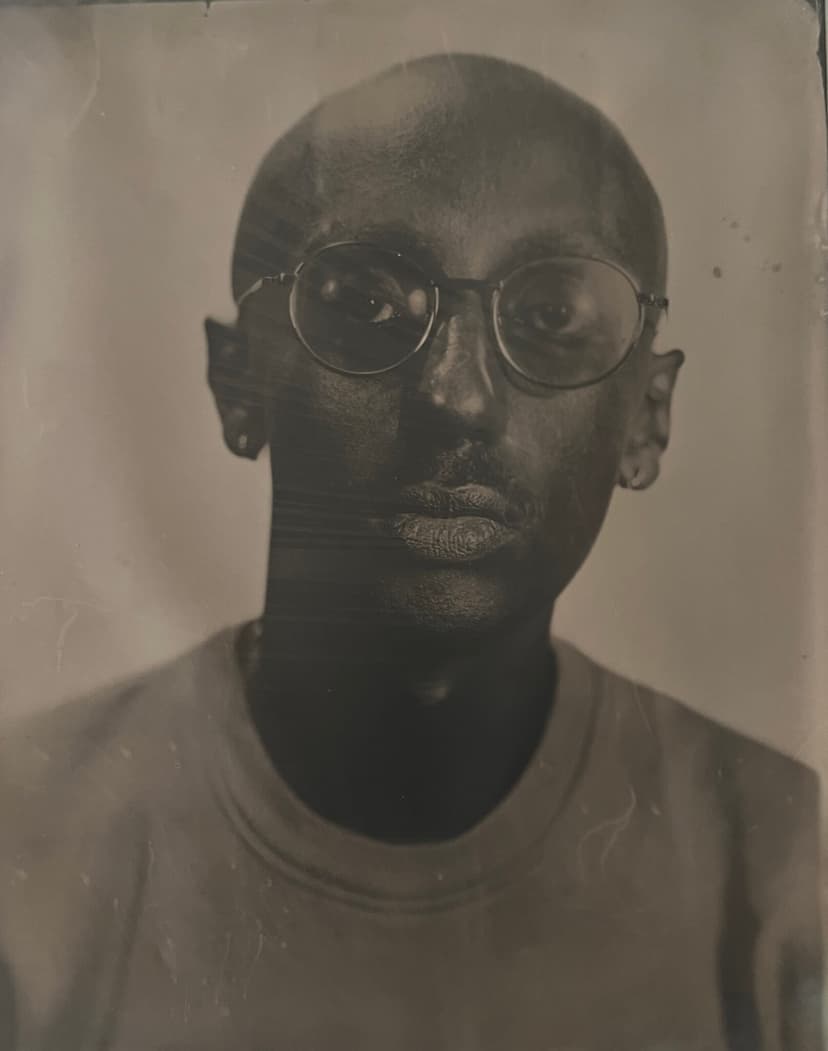

Rivera, a “new renaissance” artist and recent graduate of the Longy Music School of Bard College in Cambridge, has worked for the City of Boston’s Racial Justice Equity Initiative and in 2022 founded the Artist Initiative for Revolution (AIR). The collective uses art as a catalyst for social and political movement via intercultural exchanges and by hosting community spaces for creativity and justice-oriented work.

Gaither, nearly eighty years young, shows no intention of slowing pace in steering the NCAAA. Though the museum has been under construction for several years, he remains passionate about the impact of the NCAAA’s work and optimistically committed to its future. As the next generation of organizers rises, Rivera, twenty-two years old, has taken up the torch. In a frank discussion, Gaither and Rivera’s winding conversation touches on the history of Negro spirituals, Black studies, and Black art movements while also examining not-for-profit funding structures in the arts, the politics of space and development, and the importance of considering all that can accompany a life of service.

Introduction by Alula Hunsen.

The following conversation has been edited and condensed.

Danny Rivera: I was born and raised in Boston. My parents being community leaders has greatly influenced my work of justice seeking. I grew up singing in the church and eventually made my way to Boston Arts Academy, where I graduated in 2019. A big part of my artistic development during high school included reaching an understanding of the role that the artist plays in society. During my time in college, I founded AIR to hold space for a community of artists that are committed to art for social change. I knew artists would be essential to building a movement. In building AIR, I really look to your work, Ms. Lewis’s work, this NCAAA space, and the cultural traditions that are so embedded in Boston’s DNA, but also very hidden and overlooked.

A huge part of AIR’s mission is to sustain the long legacy and tradition of artistic work and cultural expansion in Boston. Studying the work of you and Ms. Lewis—from art curation and education to prioritizing a Black art agenda for social change—has allowed me to better understand where Boston was, where we are now, and possibilities for the future.

Now that I’m out of school—aside from my personal practice as an artist focused on regenerative art, Negro spirituals, and carrying the culture in that way—I think one of my other biggest obligations is finding ways to mobilize artists in service to these social movements while also preserving the history and legacy that lies in Boston.

Edmund Barry Gaither: Who were some of the singers in the area that you knew or worked with, or felt inspired by?

DR: Maud Cuney Hare and Roland Hayes are just a couple. Coretta Scott King, too. My expertise is in contemporary music, but as of late I have been creating work around Negro spirituals. And that is because that was my introduction to classical music. There weren’t many people that looked like me in the classical music industry. I didn’t hear anyone that sounded like me. And my story, the story of my ancestors, definitely was not being told. So that was what pulled me through Longy, and I faced a lot of racial tension there.

EBG: Well, I’ve got a project for you. I have a very long interest in the spirituals.

DR: Really?

EBG: Having grown up in the South, Black spirituals weren’t a dead tradition. I especially think of Willis Laurence James, who was a mentor to Bernice Johnson Reagon and the head of music at Spelman when I was a student at Morehouse. So I have a great interest in that body of material. A couple of years ago, I very much wanted to do an exhibition that could draw on some of the illustrations of Negro spirituals in our collection from the work produced by Allan Crite, who published three books of illustrations of the spirituals. It’s a project still languishing, awaiting a new thrust of energy and tradition.

And there’s a rich history here in Boston with Roland Hayes, Allan Crite, Harry T. Burleigh. Since you have an interest in it, it’s a project that’ll be waiting for you when you’re ready to take on something.

DR: I’m always waiting.

EBG: It’s a good moment to think about it because we are in season again for a little while until the Trump people prevail.

DR: You’re right. Well, we’ll come back to that.

EBG: Didn’t mean to sidetrack you.

DR: Not at all. You possess so much history—and it traverses disciplines and social contexts. I believe that is a large part of the ongoing and active legacy of you and Elma Lewis, who also championed arts across all disciplines.

EBG: Well, I’m a visual arts person by background, but it’s not possible to appreciate the vocabulary of a single discipline of the arts. To understand the cultural impact you have to really see it broadly, and not even just the aesthetic arena, but the sociopolitical arena. And in terms of the Black world, the Black world is in every sense a global environment. You can’t really talk about Boston without some discussion of the Caribbean. And even if you switch to the Caribbean, you’re doing French Caribbean, the Creole Caribbean, Spanish Caribbean, as well as English Caribbean, and you’re doing continental African in that mix. In that matrix, new work emerges. And I’m always encouraging new work to embrace the complexity of identity.

DR: Over time, I have found artists that are committed to that. And that’s really why I keep bringing up regenerative art. Art that brings us back to the power of our lived experiences, one that awakens our humanity. While I believe this practice has declined over the years, there remain artists and cultural bearers committed to continuing the tradition: the ability for artists to be storytellers, to upkeep these stories, to be the preserver.

EBG: I think that certainly the largest obligation that an artist has is the struggle to be honest in finding their voice and vision. Because there’s always competition. And you may not stop to ask yourself: Which road is your road? You may be swept up by what has an immediate dividend, but that might not satisfy you from the inside out. The power of art is when you can tap the source in yourself of something that needs to become.

No one can give you the content and you can’t copy the content. You have to originate the content. If there’s no content that’s driving the process, it doesn’t matter what the vehicle is.

And I think what you have to realize when you are working with that kind of struggle is not everything is the masterpiece. You have to do a lot of work to find the work that balances all of those elements powerfully. So I like to think that people like myself who are interested in trying to create platforms for work to happen, our job is to try and make a dialogue that supports this kind of growth.

DR: As I continue this work of arts advocacy and racial justice, I am better understanding the importance of community accountability and engagement both at the local and regional level. Artists have a unique opportunity to build communities of solidarity, to change the narrative.

Take us on your journey toward creating a platform for Black artists in and beyond Boston. Can you share some formative experiences and individuals, groups, or spaces that brought you to your life’s work?

EBG: When I went to Morehouse, I had never been in a museum before. I mean, it wasn’t something that was in the mix of what you got exposed to in segregated schools. But it was a moment that was grounded in its own history. What would later become Black studies was fairly routine in the segregated schools of the South in that Black teachers took on teaching Black history. And the remnant of that, that still exists in the environment where we are now, is what is Black History Month. And within that same closed network was the Negro National Anthem and Black spirituals, then called Negro spirituals. When the National Conference of Artists—which had started out as the Annual Conference of Negro Artists—sought to build a network of artists talking to artists, they did so mainly from the platform of historically Black colleges and universities and certain large figures in a limited number of large municipalities. But as far as the sort of big art world was concerned, they didn’t exist.

So when I began studying American art at the graduate school level, I was in art history at Brown, and, you know, I’m studying all of these stories that make up “American art.” But nowhere in that story were the people I had seen at the National Conference of Artists or the people who became the AfriCOBRA movement. So this entire community in which there had been an artistic life going on all the while was invisible to this larger enterprise. I’m giving this larger view because Boston is a subset within this bigger discussion.

DR: Why did you choose Boston as the place to do this work, to amplify the work of Black artists?

EBG: I don’t think it’s as geographically deterministic as the way you phrased it. I came to Boston to consider joining the NCAAA and the Museum of Fine Arts. I didn’t know what either of them meant at the time. I had been in New England for graduate school. Then I went back to Atlanta and I was a teaching intern at Spelman College. I got an invitation from the Museum of Fine Arts, and I had friends in New England, so a free ticket seemed attractive. So I said yes, I’ll come. Now, what had happened at this end was Ms. Lewis had been pressuring the MFA and the museum school for a few years, saying that she was going to need their help. Ms. Lewis had founded the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts in 1950, and in 1966 she had founded the Elma Lewis Playhouse in the Park. These gave her a very big platform that was recognized throughout the city. And she was a formidable personality. So everyone knew her and gave her space when she demanded it.

DR: I’m glad you mentioned the early days of the Playhouse in the Park. I think that legacy continues to inspire Black arts activists, including myself, as a model for activating Black neighborhoods and promoting artistic voice and freedom as a gateway to truth. Could you talk about how the program came about? Especially what resources were needed to make it successful?

EBG: The first season [of the Playhouse] was an effort to bring performance to the community of Roxbury in the summer. The inspiration for it had come to Ms. Lewis from Joseph Papp’s Shakespeare playhouse in Central Park. She asked him how he got that done, and he told her, “This is the secret: Don’t ask anybody. Just do it. And when they come for you, people will save you.” So that was sort of the attitude.

Franklin Park had been abandoned largely by the city because the communities around Franklin Park had ceased to be predominantly white. So she looked at Franklin Park and saw a whole different possibility there. There was the ruins of a municipal building that had caught fire earlier. She saw that and thought, ah, there’s the spot for starting the Playhouse in the Park and corralling local resources—mainly local construction companies that were Black and community based and volunteers. But the first year of the Playhouse in the Park was not successful. The first year, she had the Boston Pops Orchestra bring A Midsummer Night’s Dream and it didn’t go over so well. So the second year was a radically different idea. That began the tradition that brought Duke Ellington. It ran from the Fourth of July to Labor Day, every evening, weather permitting. It was a schedule of programs that were made up of some nationally known figures, some regional performers, and some local performers. It was free.

Financially, there were interesting dimensions to how this whole thing was possible. We could save money because the Elma Lewis School had a number of performing entities that grew out of its teaching in music, dance, drama. The school had a sewing and costuming department and technical theater department. The Playhouse became a way to integrate all of those elements without having to buy them. But we were always out asking people for money and offering [performers] less than we thought they were worth but what we could afford to pay.

DR: As an organizer in service of grassroots movements, the philanthropy model in the arts that you just described seems to have remained largely the same as it was sixty years ago. While the support you did receive is a testament to the NCAAA’s strong community, directing the NCAAA has not been an easy road for you. The Museum of NCAAA’s doors have been largely closed for the last three years—since 2020—due to needed and prolonged construction. We both know it is important to think about how civic policies and structures in the art world maintain systems of oppression for Black and Brown folks. Can you talk more about the impact of funding and real estate in Boston on your work with the NCAAA?

EBG: I don’t know if I would say distinctly Boston. Here’s what I would say, and this is a bit of a harsh criticism. The way support for not-for-profit entities goes in our country is this: Support goes most quickly and most easily to the already privileged. So the people who run the MFA or the Boston Symphony Orchestra glean off the money from the top, and they have a large machine to keep delivering that.

Everyone else who’s aspiring to get the consideration of patrons, not only do you not have the machinery, you are required to overcount for whatever pittance you do get. So you are cast in the role of being a perpetual suppliant. Always coming to the table asking. I’ve spent the last fifteen years trying to find a different support model. That was what we were trying to do with Parcel P3. And the whole goal of that was to get out of being the perpetual beggar. Because when you are the perpetual beggar, you never get to use your voice because you can’t afford to accept that risk. You discover that the terms of staying in the game are fundamentally conservative. That if you want to go someplace that really is a radical departure, that could open a huge new space, then not a lot of people want to go there; people want to go where they’re assured of being patted on the head or getting a gala.

The donors whose gifts are big enough to really make a difference were vested in what used to be called “The Vault” [a group of fourteen businessmen who created the Coordinating Committee in 1959 to steer economic and urban development in Boston]. The Vault were these keepers of the last echoes of the colonial era. They became their own bank, and they were the people who would give you something. But they didn’t. So we were putting a lot of effort into trying to raise money from suburbs at the moment when the inner city—the healthy inner city—was the social language. This is the seventies still. And there were a lot of exchanges from mainly suburban white people who wanted to be seen as behaving in ways that were liberal and supportive for the inner city. We would do a party, an evening performance, in a suburban setting for a wealthy family, and they’d invite their friends and we would hope to come away with some contributions. So we’d play the piano and sing some songs, do the whole show, and we would leave with barely more money than we could get going to our neighbors. So that was a route that we went down for a while. But it was not a sustainable route.

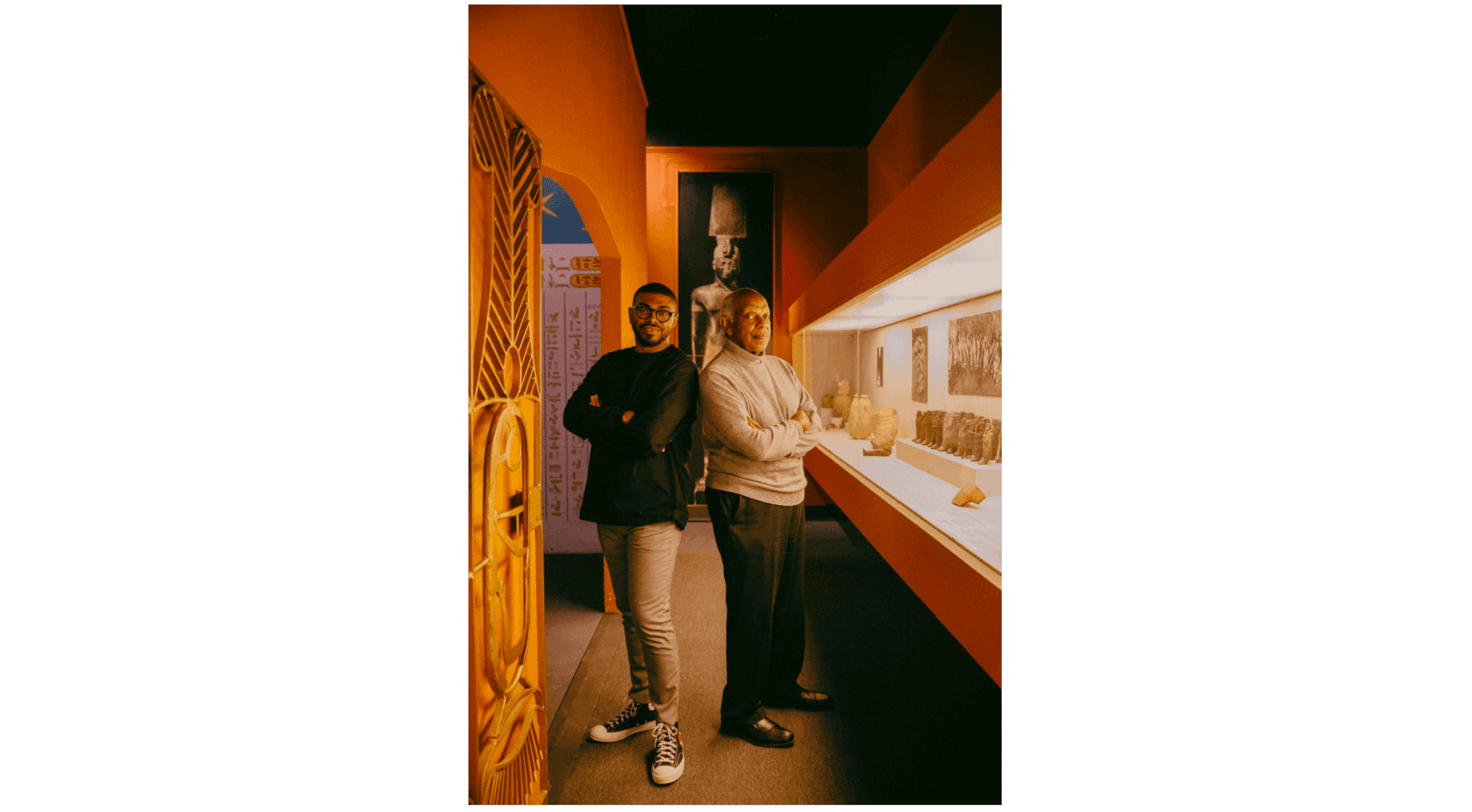

Edmund Barry Gaither and Danny Rivera peer inside a cast replica of Nubian king Aspelta’s sarcophagus. The room within the NCAAA is the world’s only accurate recreation of a Nubian tomb interior. The original sarcophagus is in the collection of the MFA, but at 32,000 pounds, it is too heavy to be moved into a viewable location. Photo by Mel Taing for Boston Art Review.

DR: What became sustainable for you? Or has it?

EBG: Nothing became sustainable for us. In the period from the very end of the sixties to the mid-seventies, the Elma Lewis School and the National Center of Afro-American Artists were a very large operation. There were more than thirty-five full-time people.

During this moment, we developed the outreach that really made significant strides in the community. But our operations were still very underfunded. We had a committed staff, a committed director, and many people who bought into the vision of change, but we didn’t have money. We were raising money today to pay for yesterday and could never get caught up paying with today’s money for yesterday.

By the late seventies, the school was effectively in bankruptcy, and it was in bankruptcy mainly because of what it owed to itself as opposed to external creditors. But it had been too impactful to be forced like an ordinary bankruptcy to liquidate its assets and close. So it was given the option to buy itself out of bankruptcy, which means raising another campaign of money.

All of the property of the old firehouse was owned by the Elma Lewis School because it was the older of the two entities. So the school defaults and the National Center buys the property. The National Center at that point becomes three things: the teaching program carried on from the old Elma Lewis School, the museum, and the performing arts. The remaining aspect of the performing arts is Black Nativity, which we did for the fifty-second season this last year.

Then the crack epidemic hit Boston, and the museum was geographically at the epicenter of it. Then we had two fires in the eighties and the NCAAA moved to its own location—the one we are in now. So the scale at which we had operated that attracted the money originally was all cut off, and we were operating at this much more minuscule level. So by the second half of the nineties, we say to ourselves, “We have to find a different model to make a future.”

And we started to look for an unrelated earned-income model. It was against that background that we, operating as Elma Lewis LLC, undertook the development effort on Parcel P3 [a nearly eight-acre plot of land in Lower Roxbury that has been vacant since the sixties]. We knew it was a high-risk effort that a not-for-profit could become a developer in Boston, especially a Black not-for-profit. But we felt that it was an opportunity so rare that we had to try to do it. We were considered for different proposals on the property between 2007 and 2019. But in 2020, that effort ultimately failed, and we returned to having to be concerned about how you rebuild a future at the present.

DR: You just spoke about a lot of really complicated things: real estate policy, fundraising, movement of money around this city. You’ve helped put things in context to show it’s not just an issue in Boston—it’s something that’s happening nationwide. But the effects of it, the impact that it has in the city, are long- lasting. The story that you just told spans decades, and it feels like even more of an uphill battle than I think we could have ever anticipated. This is a story of the ongoing struggle for financial autonomy among Black communities in and beyond Boston and the importance of situating local arts ecosystems within the context of race and class. This is a story of the dominant sphere around art that marginalizes those who don’t hold certain privileges.

As an organizer for grassroots movements in the spirit of regenerative art, I’m thinking a lot about how art is a portal for relationship building. I’m thinking about how abolitionist principles have to be rooted in art but also in neighborhoods. While you are a curator and a scholar, you are, at your core, an organizer who has established a legacy for Black artists here in Boston and around the world. Your and Elma Lewis’s work remain in our collective memory, and your cultural and social impact is indelible.

I am a part of the younger generation who are leading creative enterprises and are trying to make it in Boston. Finding the money to start and sustain artistic endeavors and cultural support for BIPOC artists in Boston is difficult because power and resources are concentrated around established, white-led institutions. This is why we started AIR, to provide support and redistribute resources, but it has been an uphill battle finding the financial support—we’re fighting against a large system of inequality rooted in white supremacy. The same models that weren’t working for you in the seventies are still not working. Yet at eighty years young, you’ve remained committed to the struggle.

I am at the very beginning of founding my nonprofit and my mission as a creator and an organizer. You are still doing the work that you began in the 1960s. What guidance do you have for the next generations of organizers?

EBG: Well, I would strongly urge anyone getting ready to go down this road to talk to people like myself who’ve been on it for a lifetime. Both because you may see things that we didn’t see, but also because I think most of us are committed to the same thing and would say what we think is helpful.

I think it’s very helpful to know that this is going to be a hard struggle and it’s going to require that you make some big decisions. For example, what can you realistically expect from a board? As a director, you’re trying to inspire them to want to go the same place that you want to go, but very often they may be wanting to take you someplace different. So there are a lot of those kinds of questions that talking to people who have been working at it for a while can help you clarify. They don’t necessarily answer the question for you, but they help you see sort of what’s at play and figure out your way through it.

When you look around the country—I can say this with actually some amount of pain as well as passion—there have been many absolutely brilliant efforts in the cultural arena by significant figures. I think of someone like Catherine Dunham, who introduced Caribbean and African dance to American Dance Theater. I mean, many people like that who gave their whole lives and work to making something, and then, a generation after their death, the organization doesn’t exist. And when I came into this particular enterprise, I was twenty-five, and I wasn’t thinking of it as a lifetime. I had a five-year plan. So now I look at this and I have to say, I don’t want it to be what all of those other things were, which is the remnant of a dream that got bought with passion and love and labor but didn’t achieve permanence.

DR: Is that what kept you here for longer than five years? That dream?

EBG: Yes. I would say at various points along the way, I stopped to look at myself. I didn’t get married until my fifties, so I kept myself so I could be very devoted, not just in my time but in my resources. I didn’t design my work as a career thinking of what would be in the bank and what would be retirement. I did it thinking what would stand as the body of the work, those kinds of decisions we owe to younger people who come into this enterprise. It seems far away when you’re young, but if you are around long enough, it will come to be real. And you might consider, “Should I have thought about this differently when it might have made a difference to think about it differently?”

DR: It sounds like you made a sacrifice in a way.

EBG: It is a sacrifice, but that’s not unusual because almost anything outside of a typical career will demand a sacrifice. I’m trying to say, if you talk to people who have been on the road that you want to go, you’ll have a better sense of what it costs. And you’ll have a better sense of at what point you decide maybe you’ll do something else. I mean, there were points at which I looked at what I was doing and I said, I’m too far into this, too invested, to back out. At the same time, I was not far enough through it to come out the other end. So I choose to stick with it and try to make something happen that I still believe can happen. I’m just saying that ought to be a decision and not a default. And in order to decide it, you really need to talk to people. I would say, in my own experience, I could have benefited from better mentoring. So I would like to be a very willing mentor for things that I think would’ve been helpful for me to have understood at earlier points in my life.

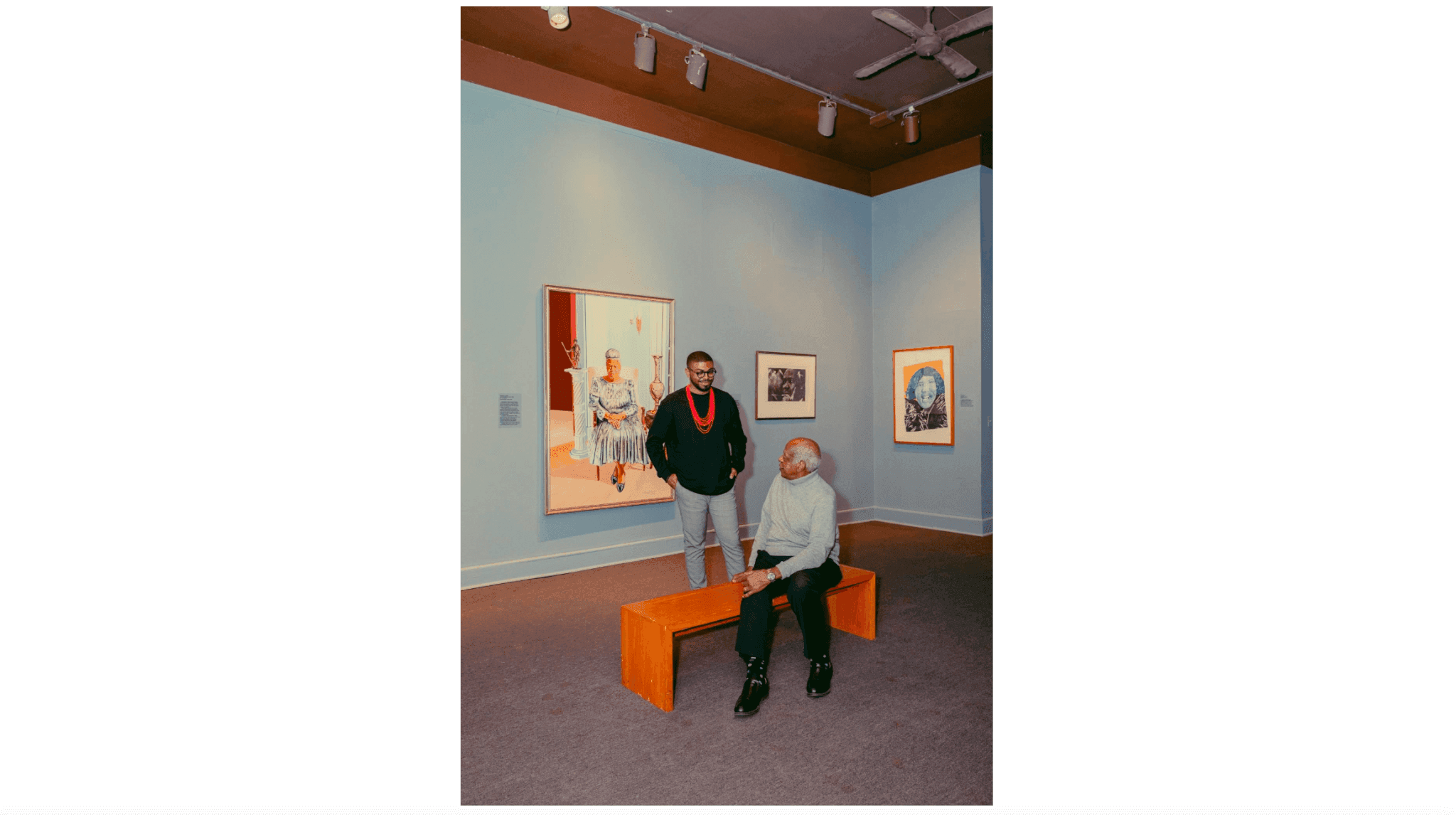

Danny Rivera and Edmund Barry Gaither in front of a portrait of Ms. Elma Lewis inside the NCAAA’s gallery. Photo by Mel Taing for Boston Art Review.

DR: What is your wish and hope for this space that you have built?

EBG: I would like to see it sustained, and I’d like to see it grow more independent and less dependent. I think I’d like to be able to say to myself, I gave it my best. If you give something your best, you still can’t guarantee it because you don’t hold the future. But what you can guarantee is what you’ve put in, and what you’ve put in should stand on its own merit.

DR: What do you think Ms. Lewis would say to you if she walked in here today?

EBG: [laughs] That’s a really hard question because she would expect that I and the others who were like lieutenants to her have, to quote Adam Clayton Powell, “kept the faith” and continued to fight the good fight, which is to try and realize the vision that is embodied in the National Center.

DR: What was the last conversation that you and Ms. Lewis had before she passed away?

EBG: Ms. Lewis was diabetic and the diabetes was a serious encumbrance in her last years. She died at eighty-two. I think our last conversation—not about justice, small talk of life—was about Black Nativity because she remained at the center of that production until she died. Because in it she saw children, and children were fundamental to her idea about teaching. Her idea about teaching was that children should be supported in their autonomous creativity and that children could do anything, but only if adults didn’t teach them to fail. And adults, she felt, taught children to fail by teaching them to be frightened—to fear failure and therefore not to have the daring to fully become themselves. And the world is much more comfortable with people who are predictable or who follow a trodden path—who can be counted on to behave in a certain way. It’s those who create tension and disruption on whom life depends because there would be no arts if everything were rosy. I mean, there’s no artistic urgency in paradise. The whole business of being creative is about what you do with tension and possibility.

This piece was originally published in Issue 10: RECALL, our spring/summer 2023 issue. Order it here.