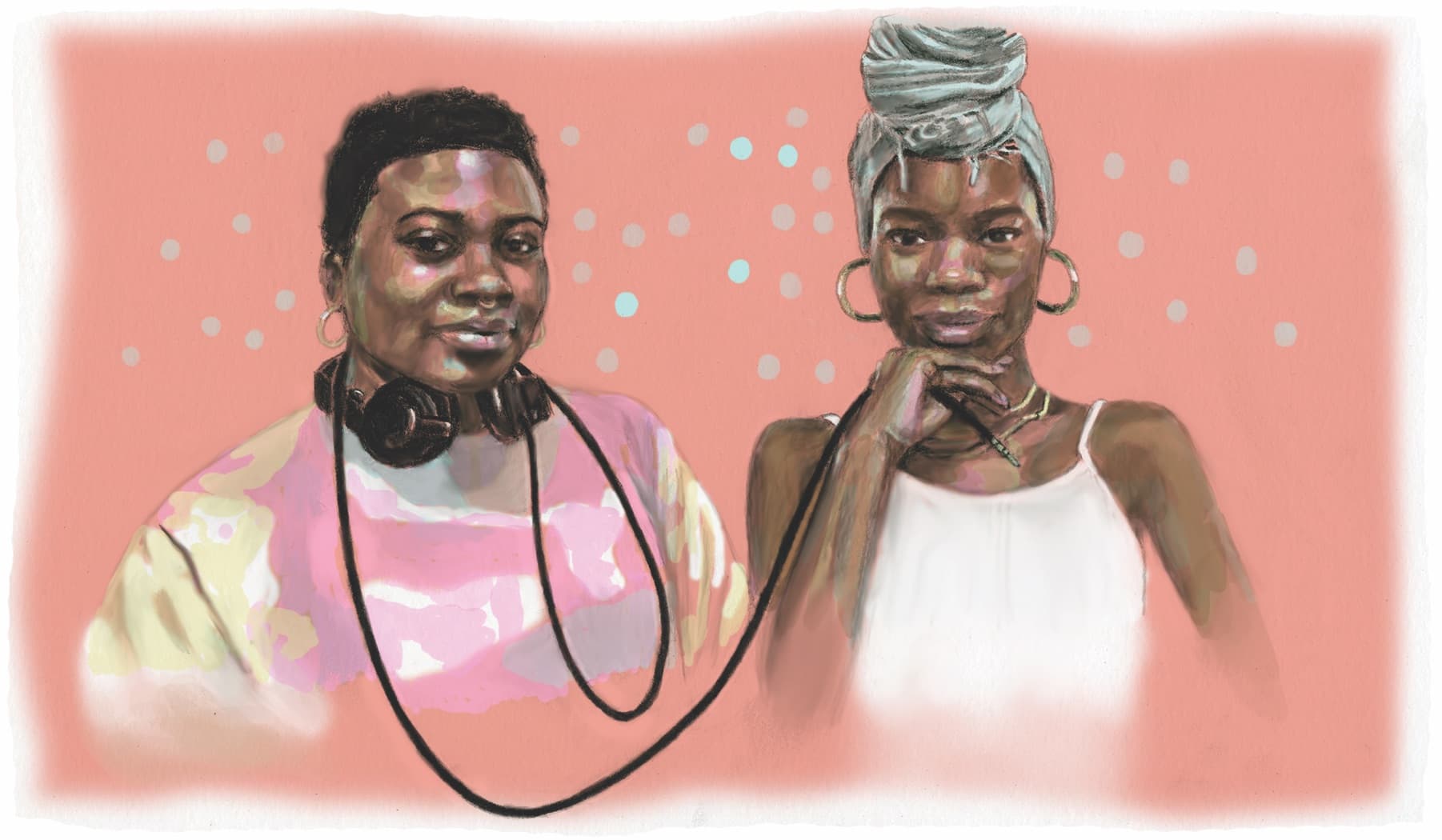

Cierra Peters and Dee Diggs are DJs, artists, and organizers who met while creating art in Boston. Diggs has since moved to New York, but the dialogue between the two of them has remained in place. Following the closures of several music, art, and performance spaces, they joined in conversation to discuss what an alternative future for cultural spaces could look like in a post-COVID-19 world. This conversation was held in late-April and published in Issue 05: No Boundaries.

Peters and Diggs are currently collaborating to present Freedom Fête: A Virtual Juneteenth Celebration, hosted in partnership with the ICA/Boston on Friday, June 19, from 8PM-midnight. It will include DJ performances by Ash Lauryn (ATL), Turtle Bugg (NYC/Detroit), Dee Diggs (NYC) and EARTHACLIT (Boston). The DJs will be donating their tips to Boston’s Ujima Project and the National Bailout Fund.

Cierra Peters: What are you thinking about now that the experience economy is all but dust?

Dee Diggs: I’ve been thinking about what it means to be a performer with new mediums to perform through. I’ve been musing on the livelihood I earned as a performer. I’m thinking about the economy of performance that has now shifted away from in-person experiences and the handshake economy of people who work in nightlife establishments like bars and clubs. From small, informal gigs to large projects, the ways people found a way to make a living in the nightlife industry are suddenly gone. I’ve been thinking about how I took globalization for granted. In the last two months alone, I planned for friends from Europe to come to New York to stay with me and play shows here. I was planning an international tour to also visit them right after in April. Travel has been a constant escape and source of inspiration for me my whole life, so the fact that that isn’t readily accessible or easy to do anymore is pretty mind-blowing.

CP: The interesting thing about this is the decimation of activation culture, like festivals, blockbuster exhibitions, and other “experiences” that we buy into—they’re all gone. Attendance as engagement was such a huge performance indicator for a lot of industries, and now that’s done. These experiences might come back in a few years, but not in the same way.

At the beginning of the crisis, musicians, DJs, and freelancers were soliciting donations, and we were seeing a lot of them—Black and Brown ones, in particular—face online abuse from the same patrons who might attend their shows. People felt so emboldened to verbally attack people online for asking for what they need.

DD: There are a lot of outrageous assumptions about how much money a working-class DJ makes, or rather what some feel we “deserve” to make. I don’t care to comment on that because I know my worth. I’m grateful to the booking agencies and agents and nightclub bookers and staff that make it all connect behind the scenes. This has affected their livelihoods as well.

CP: Recently, you did a virtual set for MoMA PS1’s Come Together (Apart). How did that come about?

DD: I was supposed to perform there in-person that day. They, instead, decided to have a 24-hour virtual event that included all of the original talent that was supposed to perform that day.

CP: They paid you in full for your set, right?

DD: Yeah, thankfully they did pay my full fee. I did a home recording and sent it to them to post on a temporary Vimeo page for 24 hours; the set I made is technically an official work commissioned by MoMA PS1 and belongs to their archives. It mimics the “had to be there” effect of cultural events in museums, but lends more permanence than a photograph of me DJing there if the physical event had taken place. If there is money already allocated by an institution to pay working-class artists, I say, GO AHEAD AND STILL PAY US. We need it now more than ever.

CP: That’s so important to me. We’re seeing institutional failures left and right, from the federal government and politicians to the nonprofit spaces and museums. Everyone seems to be implicating the “higher-ups” and not themselves when it comes to the importance of supporting workers. Arts workers are left scrambling to access unemployment insurance or loans.

Large institutions trying to cash in on club culture, but not supporting in a way that leads to sustainability for the artists that make the culture, leaves already vulnerable populations in a continued space of precarity. Recently two DJs, Math3ca (Matheus of Boudoir) and char7 of Houseboi, started a mutual aid fund for nightlife workers. It really lifted my spirits to see so much care in our community at this time.

DD: There are many mutual aid funds and grants going around New York as well! I was touched to see those pop up so quickly, too. Speaking of work, you already worked remotely before this! Can you share one tip gained from your experience on how to manage remote working culture and creative productivity?

CP: My number one tip is don’t force it and don’t rush. Pay attention to your natural circadian rhythm and decide to start your day accordingly. I learned from you not to beat myself up about those things. If you’re upfront about where you are at, people will understand and accommodate. I’d really love to see performative workaholism go away after this. We experience so much anxiety and pressure, all of us need to engage in energetic repair—especially as Black and Brown workers. I keep returning to this idea of the demands of time as a restrictive force and moving towards temporal liberation, first in my body then in my work. Ultimately, yo u create the conditions for your peace and success, so you need to set yourself up for that. Grit is important, but you need to be able to maintain it. Creative people move in different rhythms, and you have to be in flow with your body in order to make the work that you’r e meant to make.

DD: Those are all really great points. You run Print Ain’t Dead, which has a lovely physical meeting and shop space! How have you adapted to COVID-19’s effects on this project?

CP: We recently pivoted to an online-only format. We’re a pop-up and have a studio in Boston. We’ve always been focused on gathering. During our first month-long pop-up in Dorchester, we had poetry readings every week. 2020 came and dashed all my hopes of a spring reopening, and traveling for art fairs. I haven’t been to my studio in two weeks, but I’m still chipping away at designing and making improvements to the space. Last month, we held a virtual edition of the Black Feminist Study Hall, which had a few hundred sign-ups. I didn’t expect to get the support that we did. Alexis Pauline Gumbs—the author of the essay we read—and some other cuties gave us online shoutouts. It was a vibe.

DD: I think that name is so powerful: Black Feminist Study Hall. Y’all should do another!

CP: Collective study is so important! We’re planning more for sure. I’m excited to collaborate with other artists, educators, and writers this summer. #WatchThisSpace.

DD: Where is your happy place? If we were to peel back the reality of this crisis and you could go anywhere for a weekend and feel bliss, where would it be? What’s your escapist dream?

CC: My happy place would definitely be a cabin in nature right now, somewhere in upstate New York or the Berkshires. I love to hang out by rivers or secluded beaches on warm days. Taking hikes in underused green spaces has always been a spring and summer staple. Playing music as loud as I want, hearing the birds in the morning while I make breakfast. I have access to all those things in the city, but it’s not the same.

DD: I’d love to quarantine at a secluded beach island next to your secluded beach island.

CP: I wish we could! What kinds of things are helping you to feel grounded and safe, especially since you live in New York?

DD: I had days I was afraid to go outside in mid-March. The numbers in the news of COVID-19 cases and deaths were terrifyingly large and outside was cold and desolate. I moved in with the person I am dating since she had an apartment to herself. We just processed each day one by one. We took care of each other and filled our days with humor, which helped a lot. I think laughter has been the best medicine of all. Even on the days when I don’t feel a sense of purpose and can’t get out of bed, nothing gets me to sit up like a good laugh, a good morning kiss, or a morning cry to the New York Times obituaries. I’ve made some DJ mixes and did a lot of personal writing like journaling.

CP: Yeah, the obituaries are really tough to get through…

DD: Even if it’s a paragraph or a photo, it’s important to put faces to the huge number of deaths in New York. You’re seeing the faces of the COVID-19 deaths and it’s mostly Black and Hispanic middle-aged folks. They remind me of my parents or my neighbors. I feel like I’m seeing the faces of people I know and love in their faces. It’s somber, but it’s also a pillar of the human condition; everyone just wants their story to be told. Even though it’s sad to read it first thing in the morning, there’s something sweet and spiritual about holding space for a stranger who has passed. They are not just a number—always loved and missed by someone.