What’s your relationship to Boston? What’s your story here? What do you wish to see in this city’s future? What does a more equitable, just, and joyful Boston look like to you, and what would it take for us to get there? These questions and more are what “Dream Boston,” a multimedia exhibition at Northeastern University’s Gallery 360, brings courageously to the fore. Originally displayed from February 15 to April 11, 2021, and on virtual view for the foreseeable future, “Dream Boston” is designed for ongoing engagement. Its artworks not only encapsulate and interrogate our current fraught realities, but project us into the future, asking what’s required of us now to ultimately co-create the city we wish to live in.

Co-curated by Gallery 360 director and curator Amy Halliday and Boston-based playwright Miranda ADEkoje, “Dream Boston” is a triumph in transdisciplinary collaboration and artistic solidarity during a moment when arts programming was slowed due to the pandemic. Their partnership began in the spring of 2020, when the Huntington Theatre Company went dark and began inviting local playwrights to contribute to their “Dream Boston” series of audio plays. Writers were prompted to imagine a distinct part of the city set in a post-pandemic future. ADEkoje’s contribution, Virtual Attendance, envisions a hyper-gentrified Nubian Square in which Hibernian Hall and other prominent Black cultural spaces have been erased and replaced with “virtual gyms” and other frivolous developments. This devastating vision resonated with Halliday, who invited ADEkoje (a born-and-raised Roxbury resident) to co-conceptualize and co-curate a similar experiment in “imagineering” our city, this time calling upon the creativity of visual artists.play

What began as a city-wide open call—disseminated with the help of creative stakeholders in a range of Boston communities—resulted in an intimate exhibition of nine artworks by seven local artists working in community-invested and forward-thinking practices. Each artist brings their own interpretation of “dreaming” to the table, whether nightmarish or hopeful, reflective or speculative, personal or collective.

“Building” is a prominent thread throughout the exhibition, realized through the artists’ respective practices of layering, adding, fusing, and accruing. Sagie Vangelina’s canvas-based mural No Me Toques, MAR’s luscious resin-layered painting RX1386, and Youjin Moon’s richly textured video works Europa and Io abstractly render the perceptual splendors of dreaming and its power to reshape our built environments. Their emphasis on process and rebuilding asks us to embrace the idea of a work in progress: as with artmaking, making our dreams into reality necessitates an ongoing investment in the process and commitment to the vision.

Woomin Kim, Urban Nest: Boston, 2017. Found fibers from the Boston area. 65 x 80 inches.

Created from months and months of accumulating and layering, Woomin Kim’s Urban Nest: Boston is a maximalist hanging textile, woven from fabrics and objects scavenged from Boston’s streets and thrift hubs such as Boomerangs, Cambridge Antique Market, Goodwill, and the city’s unofficial September 1 holiday, “Allston Christmas.” The work is a stratified archive of the lived experiences of the people of this city—a record of celebrations and holidays come and gone; of possessions lost and phases outgrown; of shifting relationships, identities, and realities. Viewing the work is to interweave your own memories and associations into it. In my interpretation, the work also reflects the transient reputation of this city, imbued with the rhythms of coming and going, discarding and discovering. Not only is Urban Nest literally made of Boston, but it also belongs to Boston: the work has been acquired into the art collection of Bunker Hill Community College, one of the few public educational institutions in the city that serves a decidedly hyperlocal population.

Further into the show are a selection of works that take potentiality and history as springboards. Candice Camille Jackson’s And They Were Radiant is a series of portraits of young children of color from the artist’s locale of Dorchester that euphorically portray the possibilities within this city’s next generation. Jackson and her subjects—photographed in oblique lighting conditions and tender perspectives—appear to be dreaming of a city in which all children see themselves reflected and their potential nurtured.

Furen Dai, How Was Race Made?. Photo by Ruby Wallau/Northeastern University.

Furen Dai’s two works explore how two particular structures have imposed racial stratification and false hierarchies in this country for centuries: the U.S. Census and encyclopedic art institutions like MFA Boston. Part of a larger series, How Was Race Made? is a large-scale vinyl print charting the reductive ways of federally designating racial difference and societal value in the U.S. since 1850. On one hand, the work may illustrate this country’s growing diversity and inclusion, visualized by Dai’s growing stacks of classifications over time. On the other hand, and particularly in the earlier decades, the work also conjures up the effects of federal and state-sponsored strides of racial segregation and white supremacy. One such tactic that comes to mind—evoked by the work’s color-coded spatial mapping and urban gridded aesthetic—is redlining, a system of discriminatory lending policies that segregated neighborhoods, stifled African American residents’ opportunities for economic growth, and has left a legacy of racial and economic disparity within Boston’s communities today. How Was Race Made? reminds us that we must understand history if we are to begin reimagining our future. Dai’s adjacent work, Future Ruin, takes you on a virtual, 3D-rendered tour of the MFA in dystopian ruin. In the absence of the institution’s artwork, Dai crafts an archaeological and anthropological study of all the other mechanisms at play—the invisible labor, social culture, and hierarchical placement of its former collections—and poses a question: what does this building really stand for without the art?

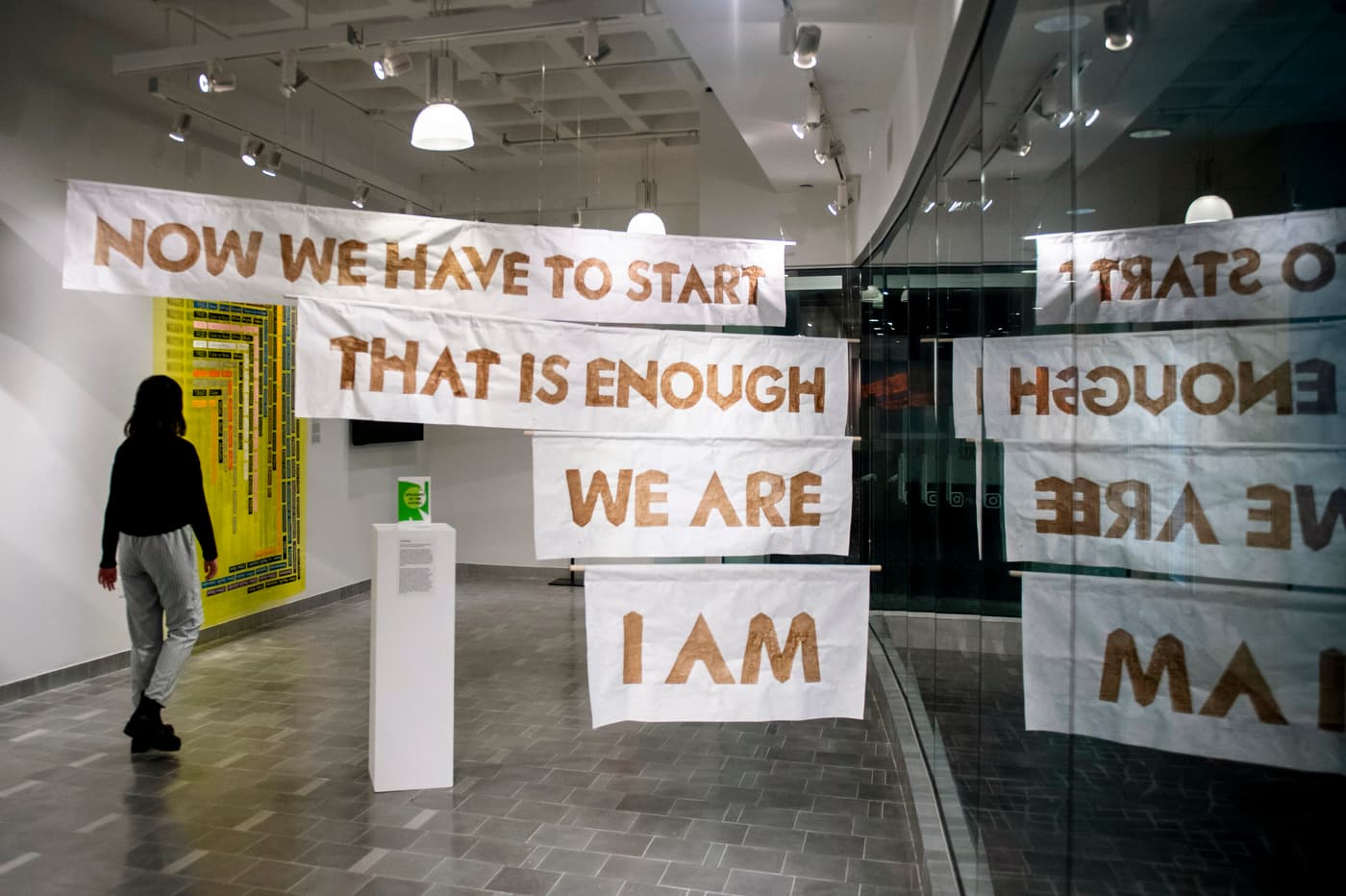

Closing out the show, Jane Marsching’s Utopia Press leaves us with the words “I AM / WE ARE / THAT IS ENOUGH / NOW WE HAVE TO START.” Borrowed from philosopher Ernst Bloch’s early twentieth-century novel The Spirit of Utopia, these phrases are repurposed and reprinted using handmade ink made from the foliage of Boston’s Hyde Park neighborhood. Simultaneously invoking the spirit of affirmation, incantation, and protest, Marsching’s banners are one final, sweeping attempt to bridge the gap between the interiority of dreaming and the real-world application of collective action.

Each of the artworks in “Dream Boston” tap into our imaginations in their own unique way, daring us to dream bigger and beyond the existing systems and institutions that often limit our potential. Together, these artists pave a path toward building a collective understanding of what a more equitable, open-minded, and communal landscape in Boston might require of us. Halliday, ADEkoje, and the artists have shown that when we come together and combine creative talents—be it artmaking, writing, curating, organizing—we start conversations that reach beyond our immediate communities and catalyze collective action. But every dream must start locally: what networks of care and support are you forging within your Boston community? As we enter a period of reemergence and a renaissance of collective experiences, it’s clear that ongoing engagement with local artists and community activism will be indispensable drivers in navigating a better future for Boston, starting now.

Dream Boston was on view at Northeastern’s Gallery 360 February 15 through April 11, 2021. The virtual exhibition remains on view here.