When the students return, so too do the hotly anticipated exhibitions. Scouring galleries, project spaces, and museums, our editors have compiled the exhibitions we are most looking forward to seeing this fall. From major surveys and retrospectives to boundary-pushing debuts and group shows, the season is filled with exhibitions that celebrate craft, care, curiosity, and connectivity.

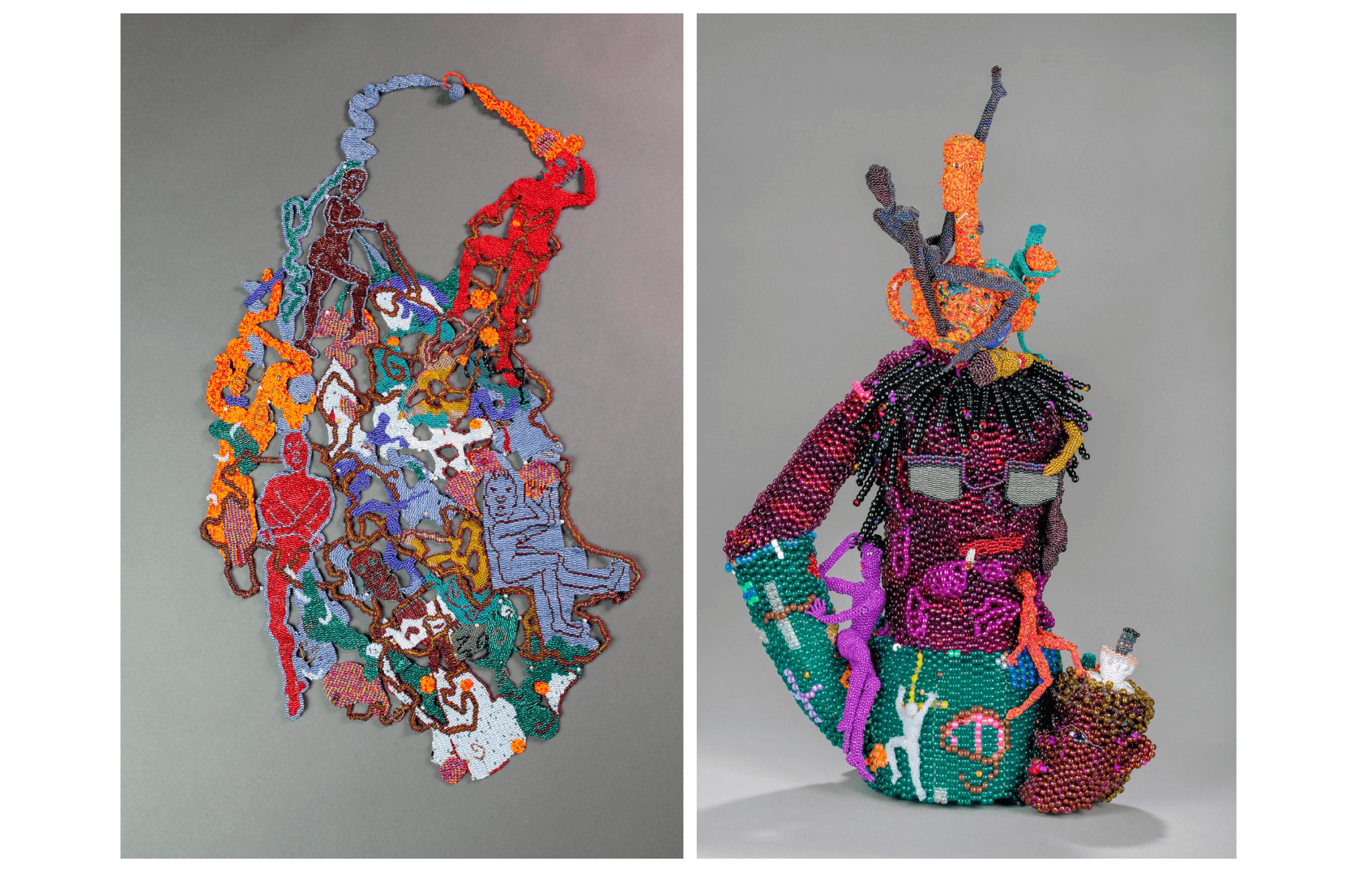

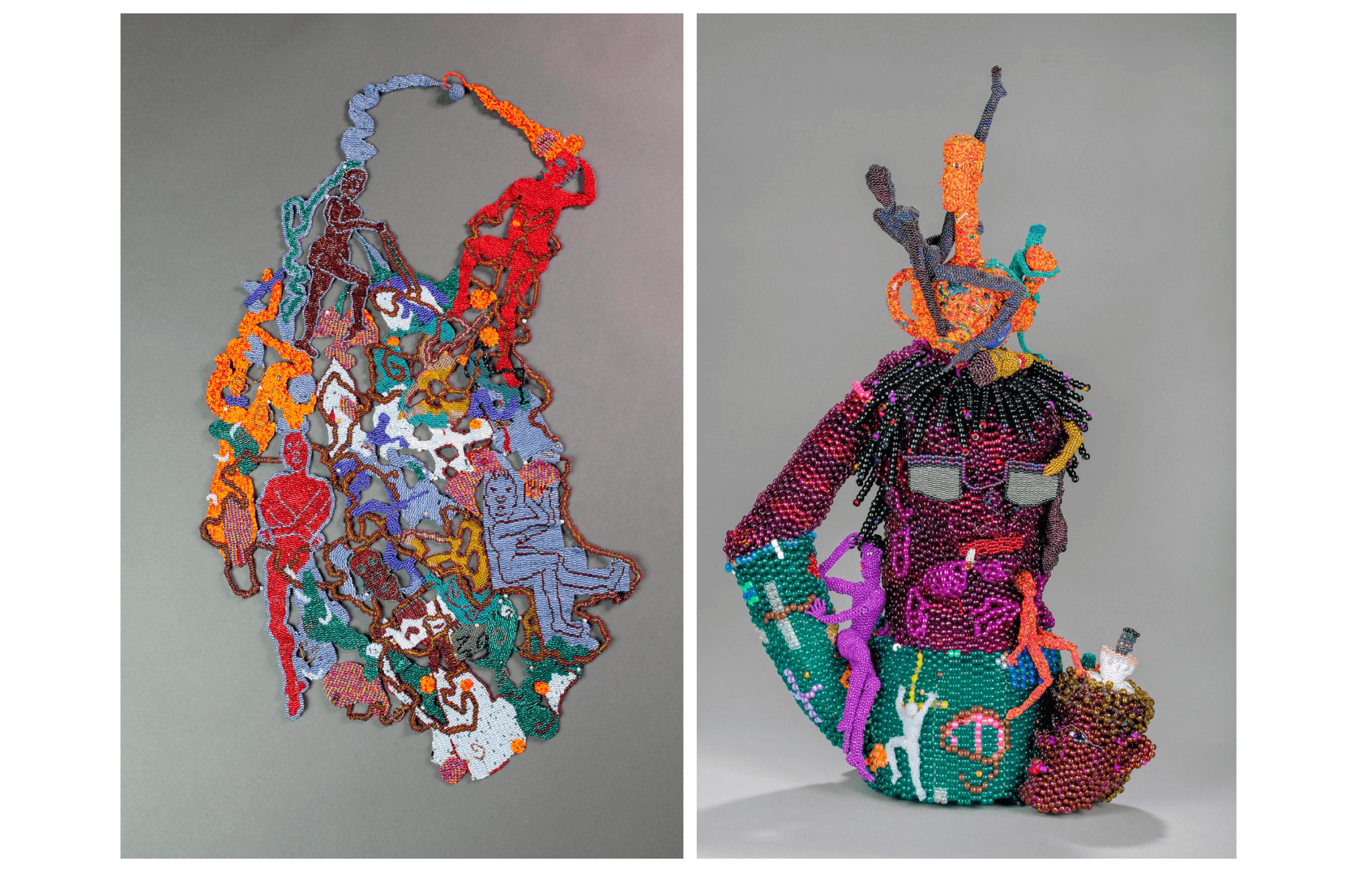

(left) Joyce J. Scott, Fairytale, 2020. Glass beads, thread, peyote stitch. 27″ x 16″ x .25″. Courtesy of Fuller Craft Museum. Photo by Iowa State University. (right) Joyce J. Scott, Mz. Teapot, 2022. Glass beads, plastic beads, thread, wire, armature, woven and peyote stitch. 31″ x 20″ x 13″. Courtesy of Fuller Craft Museum. Photo by Michael Koryta.

“Joyce J. Scott: Messages,” June 24–November 5, 2023

Fuller Craft Museum

455 Oak St., Brockton, Massachusetts

Baltimore artist Joyce J. Scott has deftly worked at the frontier of beadwork and performance art for more than fifty years. She has continued to reengineer one of the oldest artistic traditions into a radical contemporary art form by experimenting with the peyote stitch—which she learned from a Native American woman in Deer Island, Maine, while at the Haystack School of Crafts in 1976. Mobilia Gallery, which represents Scott, organized “Messages” to showcase her illustrious career, and the show has made its second stop at Fuller Craft Museum with thirty-five of Scott’s new beaded works. Scott’s hand-threaded beads and blown glass form winding sculptures and wall pieces that are alluring and flamboyant on the surface. With a closer gaze, they reveal deep layers of bodies and movement that chronicle being “Black in America.” Many of Scott’s works are also wearable, allowing the wearer to publicly carry the vivid truths. Scott’s ingenuity and craftsmanship is in the legacy of the “tender fingers of my Mom and Godmom guiding me thru folk mysteries,” she says in Love’s Incantations (2022), and in “Messages,” their mysteries live on. —Niara Simone Hightower

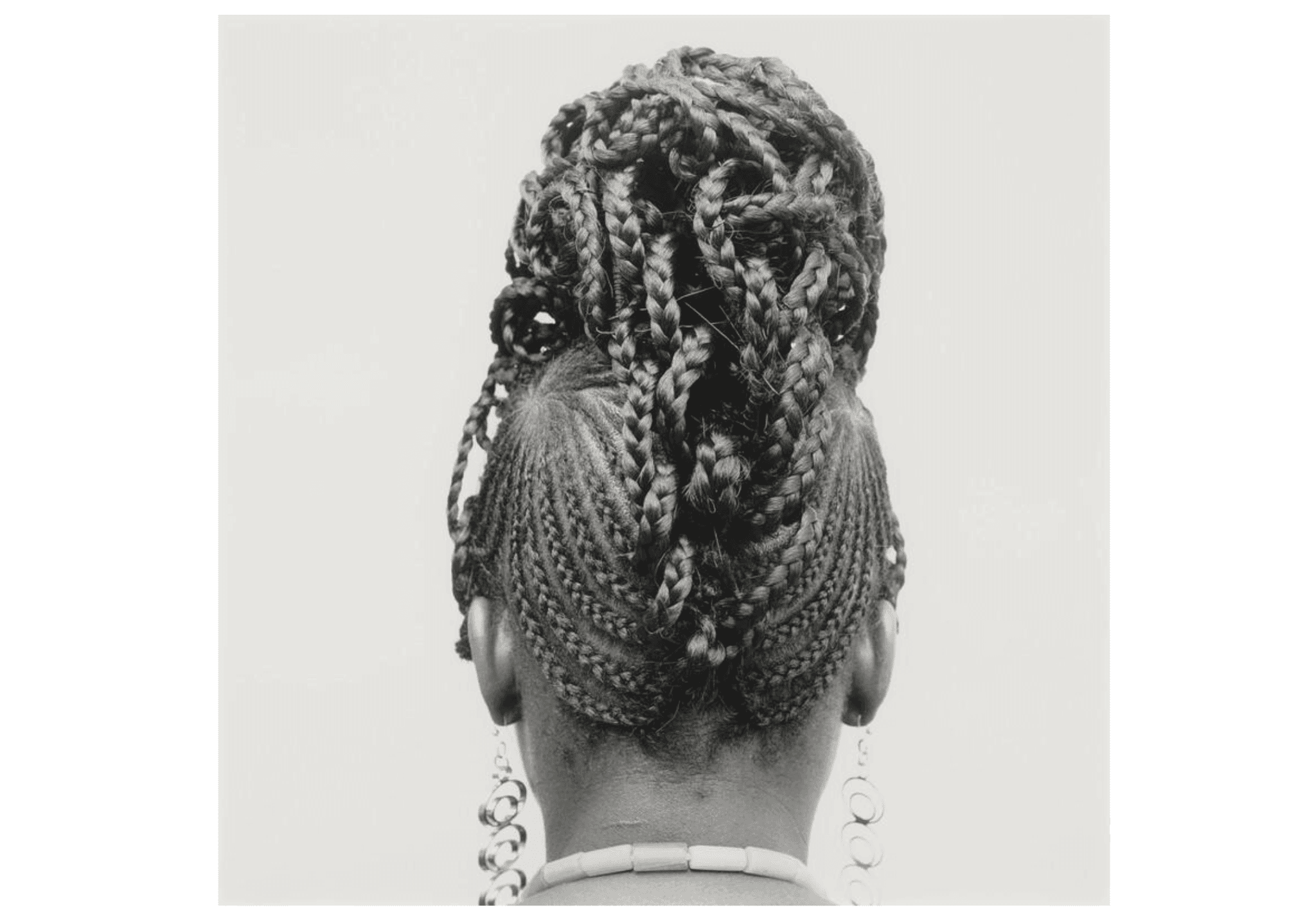

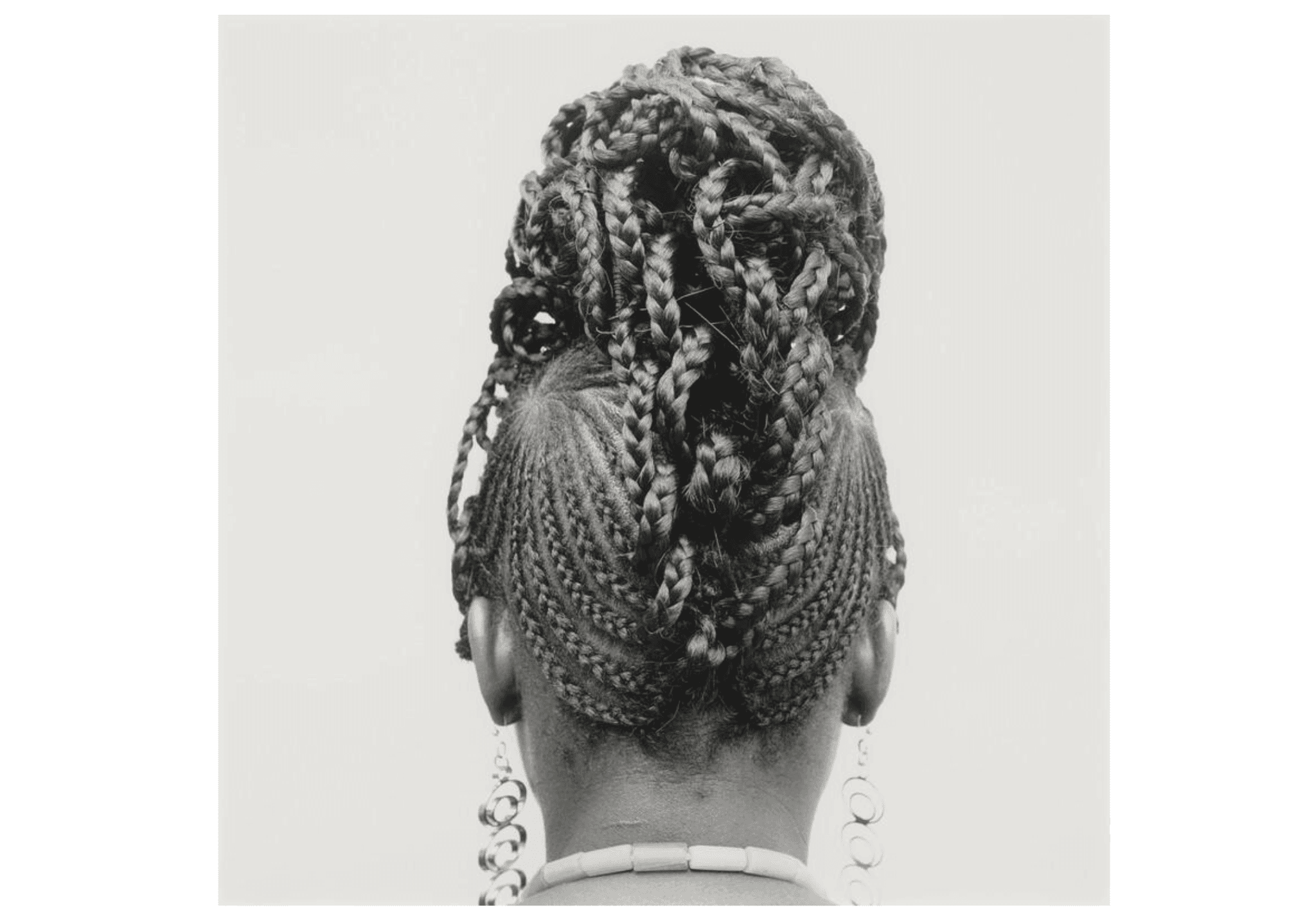

J. D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, Abebe, 1975. Gelatin silver print. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth: Gift of Robert J. Grey; 2017.55.

“Homecoming: Domesticity and Kinship in Global African Art,” July 22, 2023–May 25, 2024

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth

6 E Wheelock St., Hanover, New Hampshire

At a breaking point in 2021, curator Alexandra Thomas returned to care. She began dreaming of what is now “Homecoming: Domesticity and Kinship in Global African Art,” a rotating exhibition of over seventy-five works by Black artists, namely works by Black women artists and works of Black feminine aesthetics. Thomas—alongside multitudes of Black feminist practitioners—names craft, domestic, and spiritual work, often marginalized in Western ideology, as art forms and creative labor. Pulling historical and contemporary objects spanning centuries from the Hood Museum’s collection of African and African Diaspora art, this exhibition posits Black femininity as central to Black art and to Black interior worlds.

In Abebe (1975), Nigerian documentary photographer J. D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere shows the back of a Nigerian woman’s braids, algorithmically woven and mounted toward the crown of her head. In Baby Doll (2006), South African artist Senzeni Marasela reflects on the precariousness of childhood under Apartheid by photographing a Black woman sitting on tall green grass among a lush cloud of something like cotton—perhaps doll filling? Singled out from a series of photographs, the image shows her either sewing together a Black doll or witnessing its ruin. Gathering other works, like figurative sculptures, feminine garments, dollhouses, and Bhasha Chakrabarti’s embroidered map with jeans and indigo-dyed handloom fabric (It’s a Blue World, 2021), Thomas asks, “Who performs the labor that builds and sustains our communities and how is that reflected in the visual and material culture of the world around us?” Here, cultural bearers of Black feminist intimacy might be the fabric of life. —Niara Simone Hightower

Installation view, “Arghavan Khosravi: Black Rain,” Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University, August 3–October 22, 2023. Julia Featheringill Photography. Courtesy Rose Art Museum.

“Arghavan Khosravi: Black Rain,” August 3–October 22, 2023

Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University

415 South St., Waltham, Massachusetts

The Rose Art Museum is hosting Arghavan Khosravi’s first comprehensive survey, a show capping off a year-long residency that’s brought the Iranian-born, Connecticut-based artist back to Brandeis, where she pursued post-bacc studies before earning her MFA in painting at the Rhode Island School of Design. There’s plenty of painting on display, but these pieces refuse to be contained within the confines of a two-dimensional plane. Often working in acrylic on shaped wood panels, Khosravi creates reliefs and, most recently, freestanding sculptures that combine Persian iconography with imagery that seems summoned from a dream. These surreal tableaus incorporate evocative objects and materials—a metal chain lock might replace a woman’s mouth, and human hair becomes a weapon, flowing from a quiver of arrows. Referencing the ongoing protests in her homeland, where “Zan, Zendegi, Azadi” (“Woman, Life, Freedom”) has become a rallying cry, the results are potent meditations on repression and liberation that feel personal yet make room for mystery. —Jacqueline Houton

Cicely Carew, “Cicely Carew,” 2023–24. Installation view, “2023 Foster Prize,” the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2023–24. Photo by Mel Taing.

“2023 James and Audrey Foster Prize,” Aug 24, 2023–January 28, 2024

Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston

25 Harbor Shore Dr., Boston, Massachusetts

Curated by Anni Pullagura, the latest incarnation of the ICA’s biennial Foster Prize exhibition is showcasing three standout local talents (two of whom just so happen to have been BAR cover artists). Yu-Wen Wu (featured in Issue 05) explores the immigrant experience in precise drawings, talismanic objects, and gravity-defying installations, working quiet magic with materials such as tea leaves, porcelain, and red thread. Cicely Carew (featured in Issue 06) brings painterly prowess and soulful abstraction to a range of mediums, from photo collages that seem beamed in from the cosmos next door to Technicolor nebulae sculpted from spray-painted mesh and tarlatan. And Venetia Dale crafts surprising new forms from fragments of domestic life, creating pewter casts of everyday detritus (dead houseplants, her kids’ lunchtime scraps) and piecing together unfinished embroidery projects into lacy chimeras. It’s a wide-ranging exhibition, but all three presentations touch on themes of transformation and the passage of time—and are well worth making time for. —Jacqueline Houton

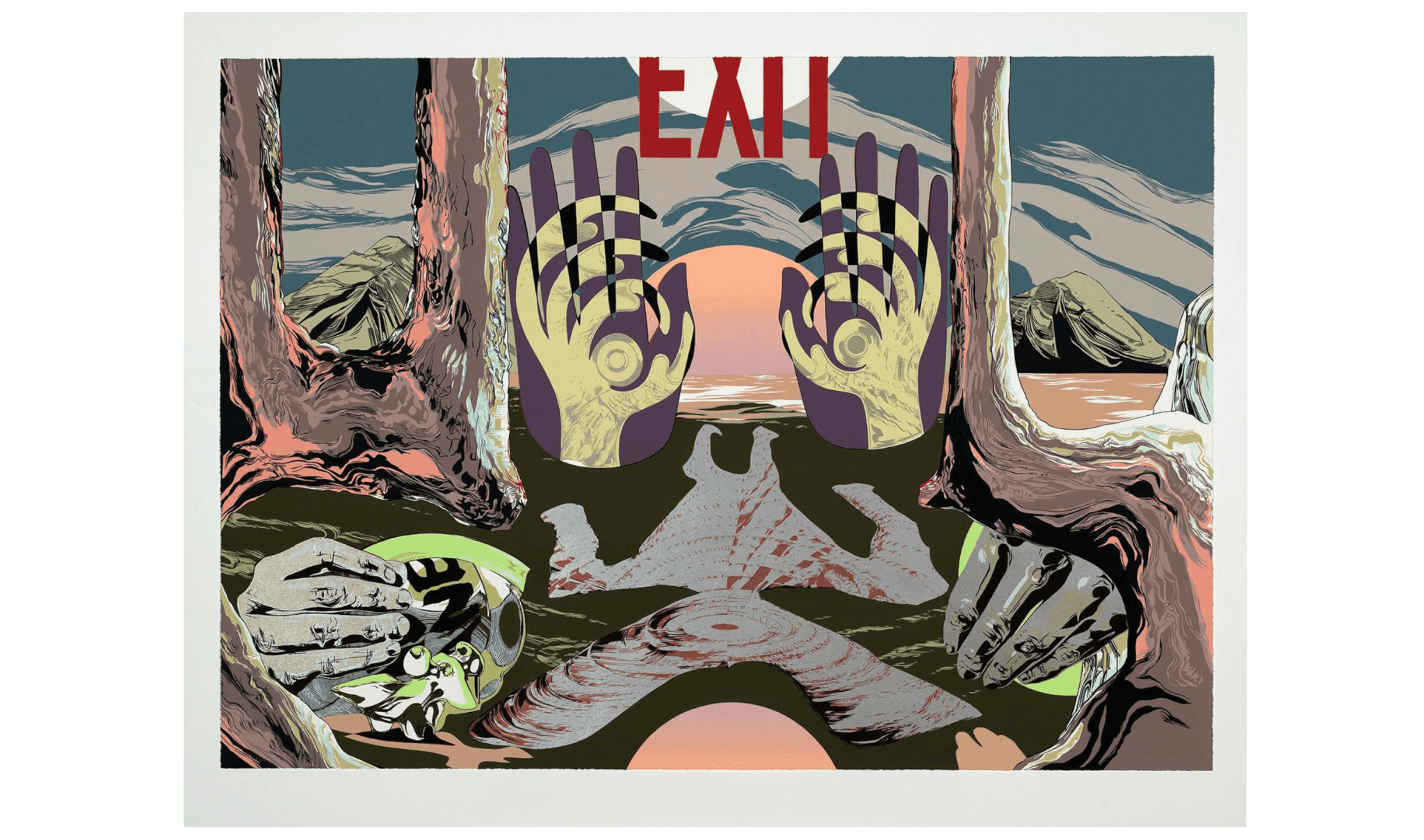

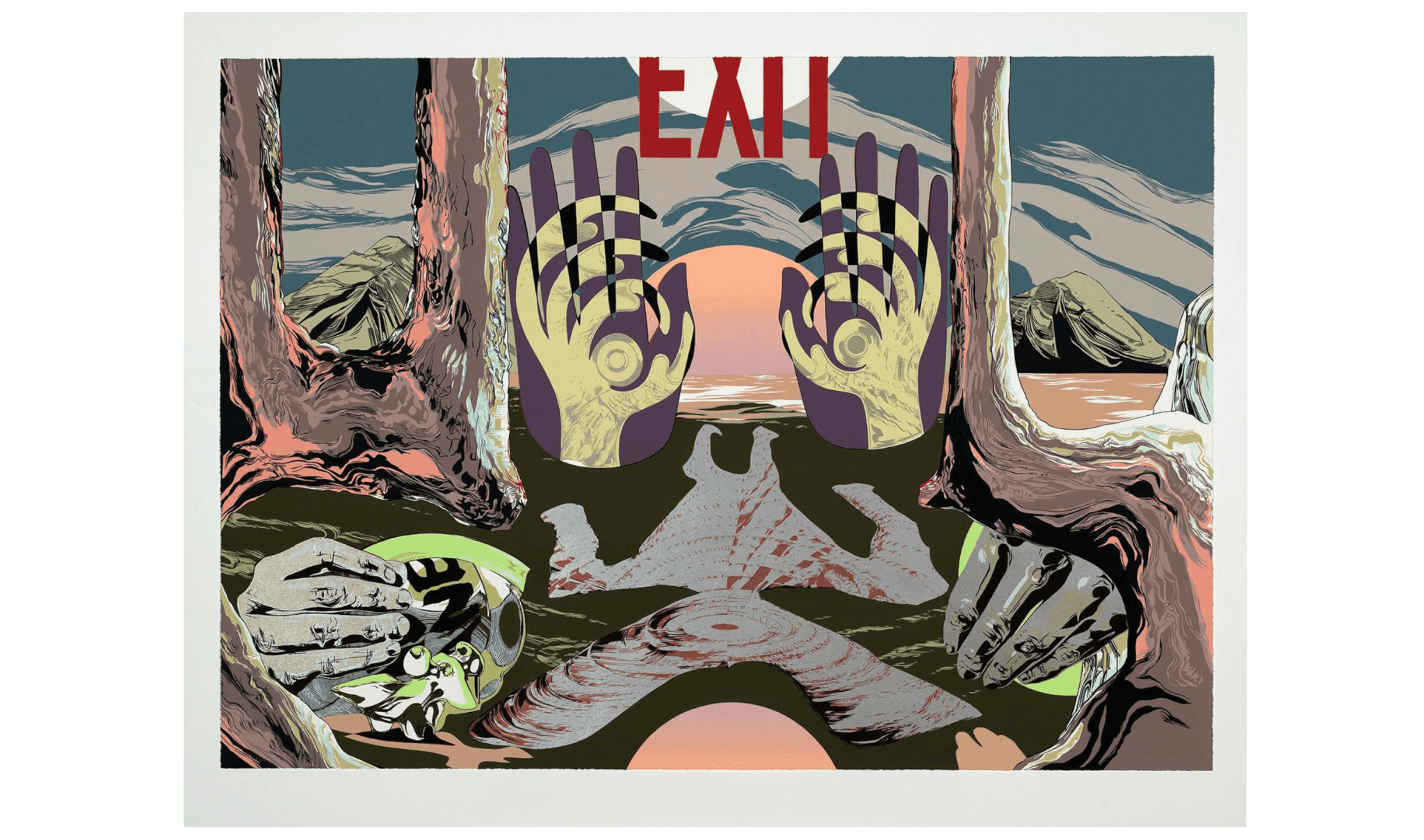

Andrea Carlson, Exit, 2018. Screenprint. Sheet: 34 in x 48 in; 86.4 cm x 121.9 cm; Frame: 33 5/8 x 47 in. Mead Art Museum at Amherst College, Purchase with Trinkett Clark Memorial Student Acquisition Fund; AC 2020.04. © Andrea Carlson. Image Credit: Petegorsky/Gipe.

“Boundless,” August 29, 2023–January 7, 2024

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College

41 Quadrangle Dr., Amherst, Massachusetts

Much has been made about the power of words in shaping culture and history (we all know, for example, what they are mightier than). Instrumental in edifying, memorializing, and contextualizing, written language can also be dangerous: by fixing a moment (an object, a person) in time, writing can fasten that which is complex and evolving into something reductive and inert. This paradox plagues all histories, but is especially felt by those rich in oral traditions, and can have devastating effects on communities that have been colonized and exploited.

Permanent forms of expression about a culture by that culture are vital—as is witnessing them. “Boundless,” Amherst College’s Mead Museum’s nearly site-wide exhibition, explores how authorship and artmaking have empowered Native American peoples, from the eighteenth century until today. Guest curated by Heid E. Erdrich (Ojibwe) with input from members from Nipmuc, Wampanoag, Shinnecock, Mohegan, and other communities, the show offers an expansive lens through which to experience the Mead’s extensive Indigenous art collection while engaging with texts—literature, cultural documents, cookbooks, and more—from the College’s Kim Wait/Eisenberg Native American Literature Collection. With additional loaned pieces, and new works by Elizabeth James-Perry (Aquinnah Wampanoag) also on view in a separate show, “Boundless” celebrates the manifold, intricate stories of Native American peoples past and present. —Jessica Shearer

Gustavo Caboclo & Camila Kanhgág, Estamos em diálogo (We are in Dialogue) da série (from the series) Onde está a arte indígena no Paraná? (Where is the Indigenous Art in Paraná?), 2020. Tecido, fio wapichana, micangas (Fabric, wapichana thread, beads). Coleção da Galeria Millan, São Paulo (Collection of Millan Gallery, São Paulo).

“Véxoa: We Know (Nós sabemos),” September 5–December 10, 2023

Tufts University Art Galleries

40 Talbot Ave., Medford, Massachusetts

There are 305 known Indigenous groups speaking at least 274 different languages in Brazil with histories, traditions, innovations, and cultures that are as diverse as the country is vast. To encapsulate the richness of Indigenous culture across Brazil seems to be a near-impossible task, but at Tufts University Art Galleries, “Véxoa: We Know (Nós sabemos)” will give North American audiences an opportunity to witness the work of Indigenous educator and curator Naine Terena. Originally organized for the Pinacoteca de São Paulo museum in 2020, the exhibition functions as a survey of contemporary Indigenous artists and collectives that transcends genre, medium, region, and art-world renown. The title, which exclaims “we know,” is a concise assertion of Indigenous agency and influence despite a history of violent erasure. It exclaims that the culture, craft, and connections shared across Indigenous communities are strong, but not monolithic. Films that showcase the mundane, installations made from ancestral practices, or artifacts that emphasize activism all seem to reverberate into one another. —Jameson Johnson

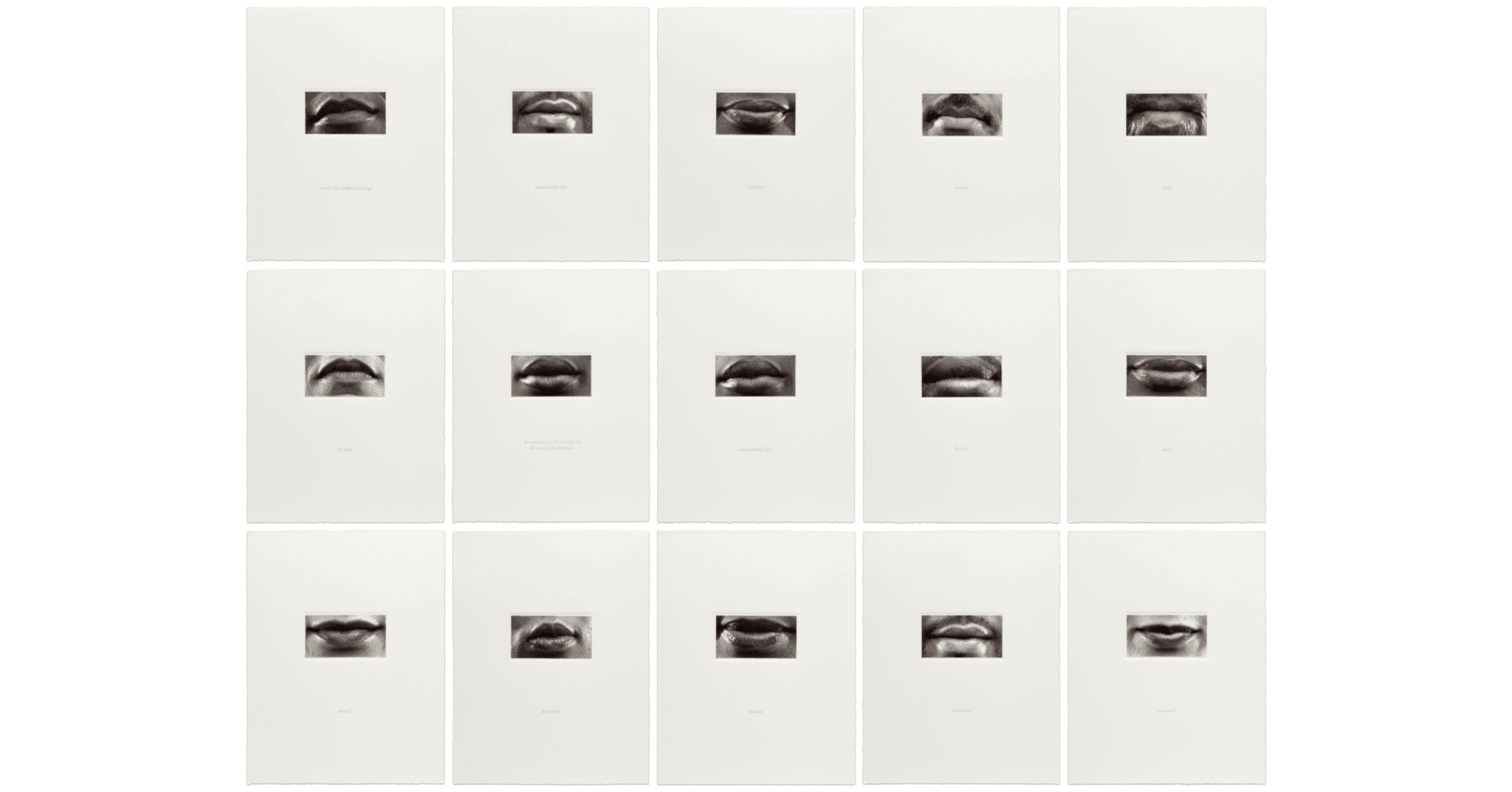

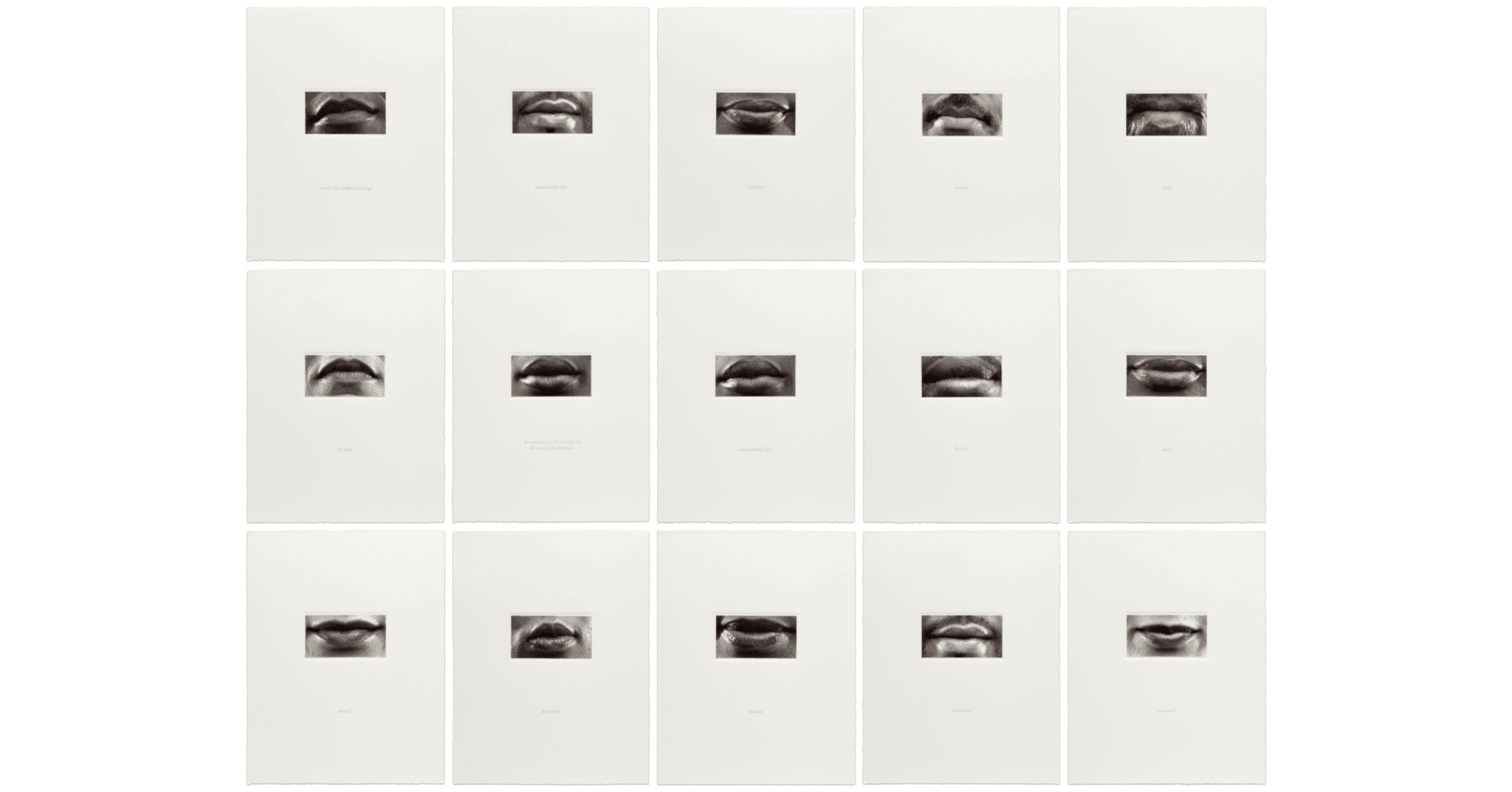

Lorna Simpson, 15 Mouths, 2002. Fifteen archival pigment prints on Velour paper, mounted on Hahnemühle Copperplate paper with deckled edge, with letterpress printed text on each sheet, with accompanying audio CD in portfolio case. Photo courtesy Krakow Witkin Gallery.

“Whom,” September 9–October 14, 2023

Krakow Witkin Gallery

10 Newbury St., Boston, Massachusetts

Following the summer show “What,” which was organized around objects made from found materials, Krakow Witkin Gallery’s fall exhibition will turn to the human form with “Whom.” Photographic portraits are the driving force behind the show, and the work on view promises unexpected moments from thirteen prominent artists. A 1935 hand-colored photograph by James Van Der Zee resembles a prized family heirloom, while Cindy Sherman’s Untitled (Under the WTC)—taken in 1980 and printed in 2001—is a chilling time capsule from the artist’s iconic series of pop culture cliches. Sets of photographs by Robert Filliou, Christian Boltanski, Lorna Simpson, and David Robbins offer numerous meditations on a single subject: artist hands, archival portraits, mouths, and artist headshots, respectively. —Jameson Johnson

Jinah Kim and Cara Buzzell, Water Stories: Triveni Sangam, Allahabad (Prayagraj), India, Jan 3, 2023. Digital Image. Photo courtesy of Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

“Water Stories: River Goddesses, Ancestral Rites, and Climate Crisis,” September 18–December 16, 2023

Harvard Radcliffe Institute, Johnson-Kulukundis Family Gallery, Byerly Hall

8 Garden St., Cambridge, Massachusetts

Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute will host “Water Stories: River Goddesses, Ancestral Rites, and Climate Crisis,” along with a series of public programs to illuminate diverse perspectives on the cultural, religious, and political significance of water. Highlighting works by Indigenous communities in the Global South—which has historically been shaped by Western imperial powers and, in recent years, devastated by natural disasters—“Water Stories” aims to humanize the effects of climate change through visual storytelling. This group show will display work from the collections of the Harvard Art Museums and the Peabody Essex Museum alongside pieces by contemporary artists Atul Bhalla, Alia Farid, and Evelyn Rydz. By uniting historical painting with contemporary expression, the show will explore mythmaking around water while underscoring the harmful legacy of colonialism and imperialism in the age of climate change. After a summer dominated by headlines about flooding throughout New England, this exhibition promises to expand our understanding of and relationship to this powerful element. —Karolina Hać

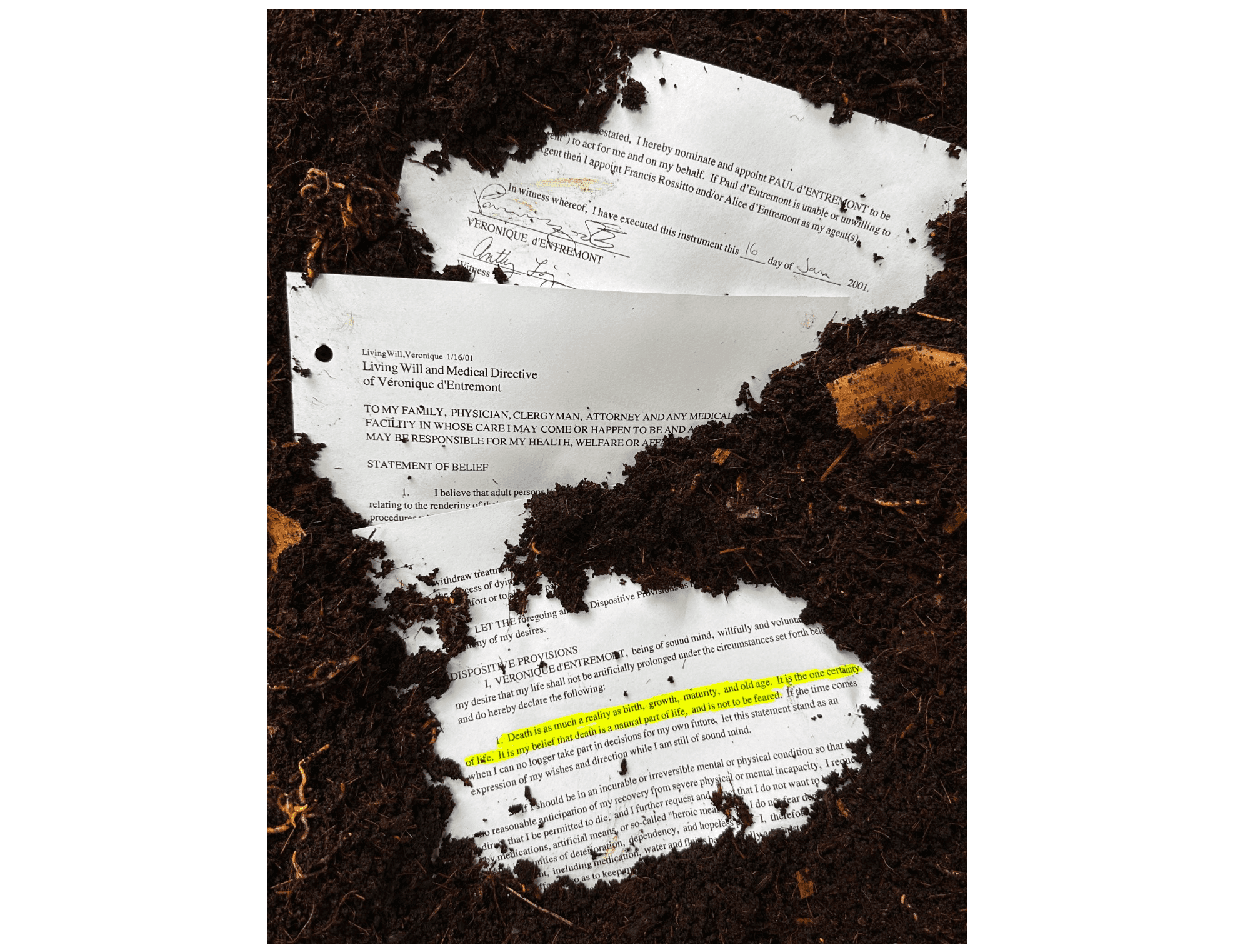

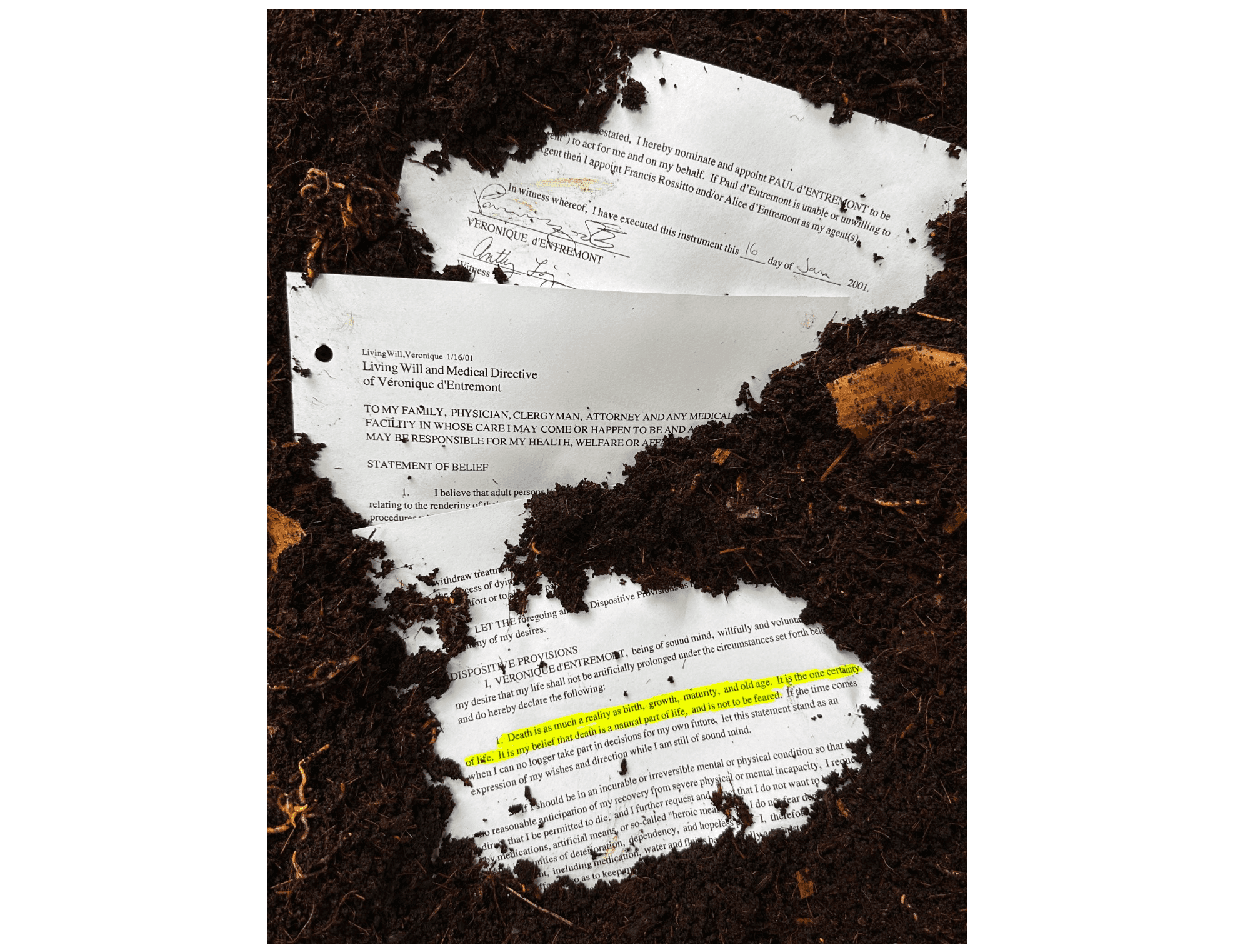

veronique d’entremont, Being of Sound Mind, 2023. composting worms, dirt, medical directive signed by the artist upon their 18th birthday. Photo courtesy of the artist.

“The Table is the Altar,” September 23–October 15, 2023

10b projects

10b Brookley Road, Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts

“The Table is the Altar,” and it’s rotting, it’s fermenting, it’s very much alive, especially when we gather around it. Over the course of five events, an installation by veronique d’entremont becomes a five-course rite honoring aliveness and cycles thereafter. At the center, a table is surrounded by three chairs from d’entremont’s childhood home. These objects are enveloped by large hanging tapestries, or “grave rubbings,” made as the artist traced the contours and textures of furniture in their late father’s house, which they now occupy. Overlaid are words from letters by their father that describe death arrangements for the family. d’entremont paints these letters with an ink similar to that used in medieval manuscripts—a highly acidic ink that gradually eats away at the paper or fabric on which it is written. Inspired by early Christian roving feasts, d’entremont considers the ritual of fellowship as a sacred mode of processing death—together moving through all of those anxieties, questions, curiosities, preparations, and spiritual acceptances.

Audiences will have several opportunities to join d’entremont throughout the exhibition’s run, including a burial fellowship in collaboration with DA Mekonnen on September 24, a collaborative program with Marcel Marcel on October 7, and an ancestor mediation in collaboration with Raqael Duarte Hunt on October 14, sandwiched between opening and closing receptions. —Maya Rubio

Polly Apfelbaum, Compulsory Figures (slabs), 2022. 50 slabs of glazed terracotta. Dimensions variable. Photo by Scott Alario. Courtesy of ODD-KIN.

“POLLY APFELBAUM: THE WORLD’S A MESS; IT’S IN MY KISS,” September 10–November 18, 2023

ODD-KIN

89 Valley St., East Providence, Rhode Island

I’ve always found it interesting that when attempting to understand the mechanics of the universe, we fall back on artful language. We look to “sacred” geometry, with its “divine proportions” or “golden ratios,” discovered using formulas with “elegant” solutions. Many of these turns of phrase have ancient origins and were bandied about during ages where the lines between art and mathematics—”soft” and “hard” disciplines—were porous and hazy. It takes a boundary pusher (breaker, annihilator?) then to reconcile them in our modern age, refastening the wonder of pure color and shape to the rigorous demands of exact sciences.

Thankfully we have New York–based artist Polly Apfelbaum, who has been disregarding convention since the ’90s, when her “fallen paintings,” hand-dyed and hand-cut fabric installations, took over galley floors. In her new show “The World’s a Mess; It’s In My Kiss,” new ceramic works now occupy ODD-KIN in Providence—a gallery dedicated to disrupting norms—referencing and furthering the concerns of her more than forty-year career. With new colors developed at Arcadia University paired on fifty terracotta slabs and 492 (!!!) pieces of cast-off clay, Apfelbaum’s multiple installations offer a joyful cacophony, a prismatic blare of fragile artifacts that beam up from their humble (or is it commanding?) position on the ground. On the wall, one hundred bright, bifurcated circles, the artist’s Hilma Heads, pay homage to one of the forerunners of geometric abstraction, a woman who, like Apfelbaum, saw beyond boundaries to tap into the sublime. —Jessica Shearer

Cristóbal Cea, Ewaipanomas y niño canibal (still on jungle), 2023. Digital animation on oil painting. Photo courtesy of Boston Center for the Arts.

“Cristóbal Cea: No Monsters, No Paradise,” September 29–December 9, 2023

Mills Gallery, Boston Center for the Arts

539 Tremont St., Boston, Massachusetts

In the Mills Gallery, Cristóbal Cea’s multimedia exhibition remixes archives of colonizers’ early encounters with Indigenous people. Diaries and letters describe and illustrate headless men and other monstrosities. Through 3D animation, these monsters are born again, and they dance strangely, tell jokes, and move anxiously around the space. These renderings toggle between the imagined and the real, rendering new creatures among us. Cea invites audiences into surreal, yet historically meaningful worlds, inciting playful curiosity as we encounter unknown territories and virtual realms. —Maya Rubio

Corinne Spencer, Like Muscle to the Bone, 2016. Video still, 10 minutes 53 seconds. Courtesy of the artist.

“The Myth of Normal: A Celebration of Authentic Expression,” October 5, 2023–May 19, 2024

MassArt Art Museum

621 Huntington Ave., Boston, Massachusetts

This fall, MassArt Art Museum will present the work of the college’s talented alumni to present a meditation on the importance of authentic expression in the healing process. “The Myth of Normal: A Celebration of Authentic Expression” is inspired by the work of Dr. Gabor Maté and Daniel Matés, who argue that engaging with art is an essential part of one’s wellness and art-making is a critical mode of self-expression. This themed “retrospective,” guest-curated by Mari Spirito ’92, coincides with the college’s 150th anniversary and will feature the work of graduates from the 1960s to today working across disciplines and media. Artists will be grouped thematically to underscore the roles authentic expression plays in different aspects of our lives. Some notable names include Freedom Baird, Steve Locke, Rashin Fahandej, Taboo!, Mimi Smith, Corinne Spencer, and Loretta Park (the full list can be found on MAAM’s website). —Karolina Hać

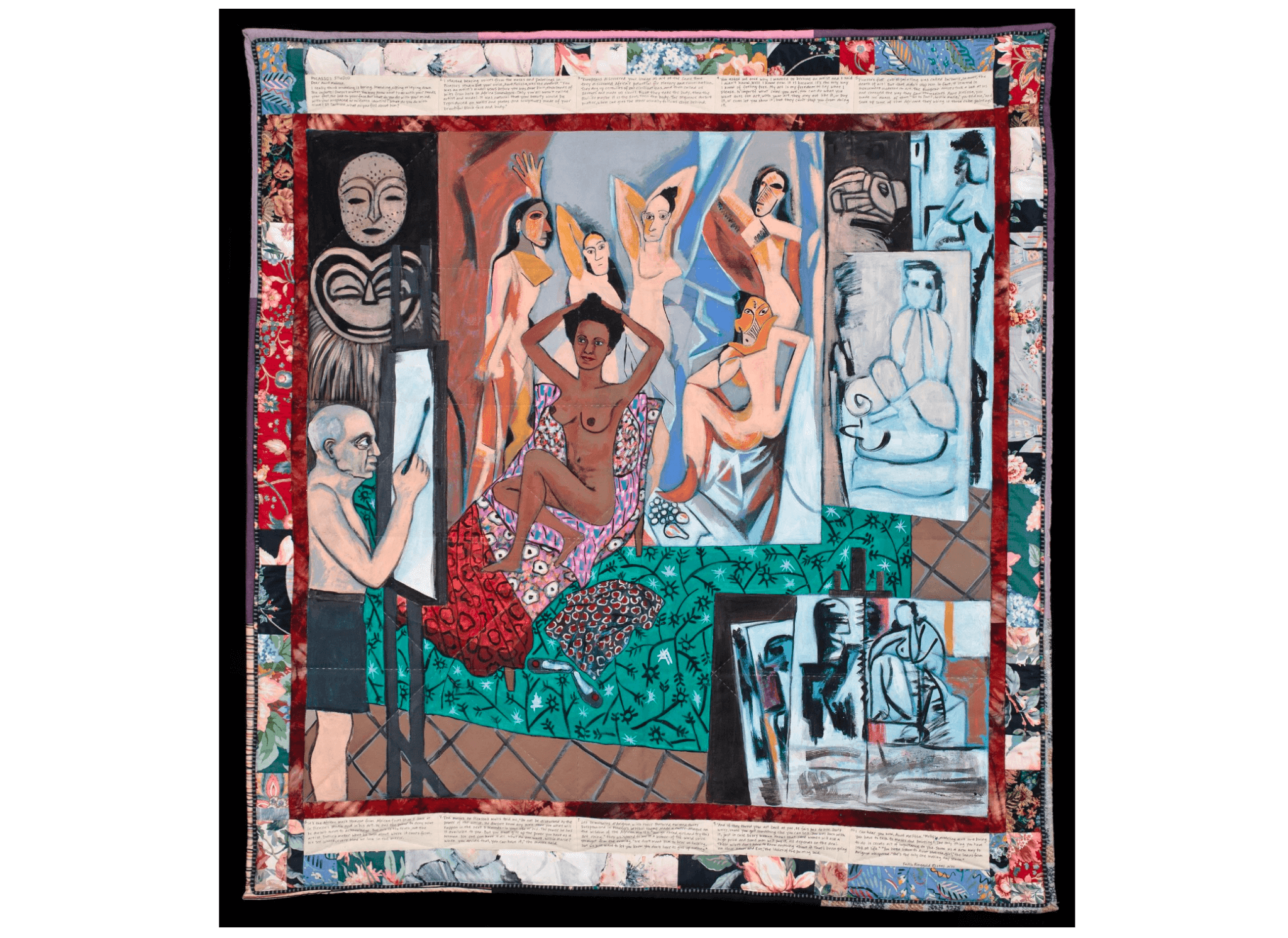

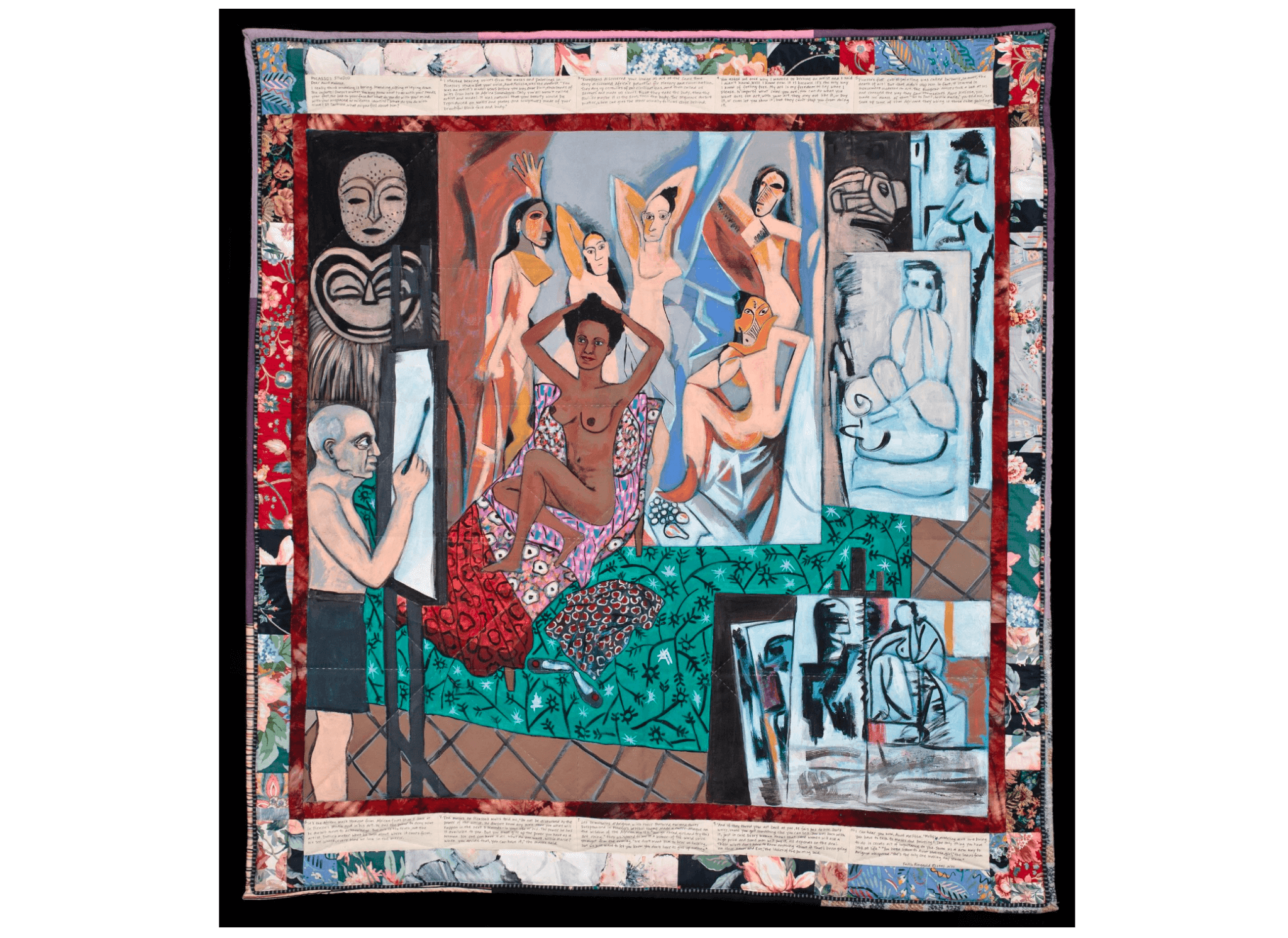

Faith Ringgold, Picasso’s Studio, 1991. Acrylic on canvas; printed and tie-dyed fabric. Charlotte E.W. Buffington Fund, 1998.148. © Faith Ringgold / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Courtesy ACA Galleries, New York.

“Faith Ringgold: Freedom to Say What I Please,” October 7, 2023–March 17, 2024

Worcester Art Museum 55 Salisbury St.,

Worcester, Massachusetts

“Faith Ringgold: Freedom to Say What I Please” is built around Picasso’s Studio (1991), a narrative quilt from the artist’s series The French Collection. Part of the Worcester Art Museum’s permanent collection and recently on loan as part of Ringgold’s 2022 survey retrospective at the New Museum, the work directly targets how history views Black women. In it, Ringgold imagines her character Willa Marie Simone as a model for Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the controversial painting of female nudes wearing African masks that was said to have birthed modern art, but has since come under fire for exploiting women and people of color cast in the role of the “other.” Fifteen other pivotal works provide thematic and chronological context for Ringgold’s piece. Given the rich layers of Ringgold’s practice, which interrogate art history, Western history, and the canon in general, this exhibition is sure to ask audiences to reconsider much of what we have been taught. —Kaitlyn Ovett Clark

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth: Only sounds that tremble through us, 2020–22 (detail). Multi-channel video installation and two-channel sound with subwoofer, steel and concrete panels, custom seating, photographic gel, 34:40 min. Installation view: “May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth,” Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2022. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar. Courtesy the artists.

“Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme: Only sounds that tremble through us,” October 27, 2023–March 3, 2024

MIT List Visual Arts Center

20 Ames St., Cambridge, Massachusetts

At the MIT List Visual Arts Center, artist duo Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme will be presenting a recent installation that is part of May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, an ongoing project that utilizes online, installation, sound, and public performance components. Postscript: After everything is abstracted (December 2020) and Part I: May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth (March 2022) have web iterations available online. These serve as both living documents and precursors to what Abbas and Abou-Rahme will present this fall. May amnesia never kiss us is strikingly audible as it is visual. The project uses collaged layers of imagery with found videos from social media, performances of music from Iraq, Palestine, Syria, and Yemen, and their own abstracted footage. By overlaying this index of videos with music and experimental sound, Abbas and Abou-Rahme examine the loss and violence experienced with forced migration. Amplifying the transient soundscape with the consumption of online content creates a dreamlike sensation, producing a ripple of experiences mirroring those of the individuals affected. We are granted access to the haunting resiliency and collective fractured memories of the migrant diaspora. —Kaitlyn Ovett Clark

Kaitlyn Ovett Clark is managing editor for Boston Art Review and the exhibitions and public programs manager at the Tufts University Art Galleries at the SMFA.

Karolina Hać is an editor at Boston Art Review and head of marketing at Höweler+Yoon Architecture, LLP.

Niara Hightower is editorial assistant at Boston Art Review.

Jacqueline Houton is a senior editor at Boston Art Review and a copyeditor at Candlewick Press.

Jameson Johnson is editor-in-chief at Boston Art Review and marketing and development manager at MIT List Visual Arts Center.

Maya Rubio is an independent curator.

Jessica Shearer is a senior editor at Boston Art Review and director of communications and user experience at the Boston College Center for Corporate Citizenship.