To ask Lyle Ashton Harris to pinpoint moments of inspiration is almost an unfair question. The artist has spent a lifetime capturing photographs and collecting ephemera, news clips, documents, and fabrics that serve as constant points of reference.

At the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis, Harris’s solo exhibition “Our first and last love” might fall into the “mid-career retrospective” category for some artists, but for Harris, it was an opportunity to remix and reconsider bodies of work that have defined his oeuvre. So instead of a monolith, we see the richness and beauty of Harris’s life spent between Ghana, New York, Tanzania, and Latin America with friends, family, and lovers. We see parties in the form of tiny slides from Harris’s Ektachrome Archive. We see the loss he experienced as a Black queer man living through the AIDS epidemic in newspaper headlines in his Blow Up series. We see police brutality in the stunning self-portrait of Harris wearing makeup and dressed as a New York City police officer in Saint Michael Stewart (1994). We see intimacy in the names of former partners. We see reverence in deep reds and golds.

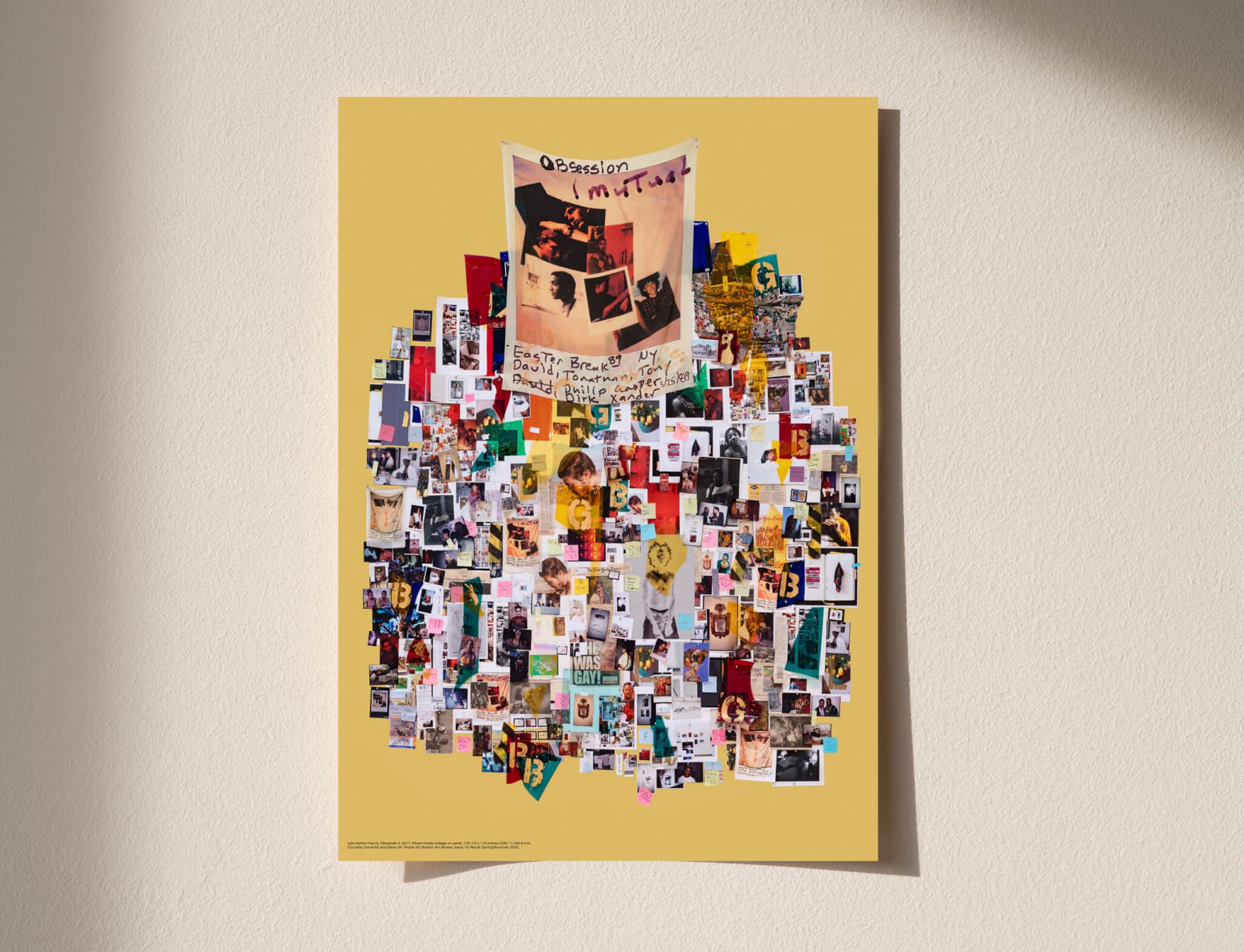

At the center of the gallery, Obsessão II (2017) takes up nearly ten feet of wall space with tacks, tape, and Post-its holding up hundreds of personal and public ephemera. In it, we see the micro and the macro of Harris’s artistry: Handwritten notes scribbled onto small paper scraps invite viewers into the marginalia of his life, while photographs of other collections of photographs remind us that we’re looking through layers and layers of his process.

The scale of Obsessão II can be daunting, which is why for his artist project with Boston Art Review, Harris has rendered the artwork in the form of a poster. For the first time, the artwork is being accompanied by a guiding document and a list of all 317 materials that compose the work. The process was tedious, yet joy-filled; Harris is constantly reconfiguring his archive, allowing for moments of surprise and recontextualization.

The following conversation has been edited and condensed.

Jameson Johnson: To me, rendering Obsessão in a form that is tangible and searchable, it feels like a moment where the values and undercurrents of your work are being brought to the surface. Specifically, materiality and tenderness. A reader can literally hold the work in their hand, and pore over the names, places, and fragments that comprise the Blow Up series.

Lyle Ashton Harris: I’ve developed several iterations of my Blow Up works over the years, but this is the first time that a poster has been produced. I’m super excited about it, particularly given its ephemeral quality. In 2001, while at the American Academy in Rome, I began gathering materials for what eventually became my Blow Up series. In 2004 I produced Blow Up I, which was first exhibited at Rhona Hoffman Gallery in Chicago. Even then, there was something about its ephemerality that drew me to continue exploring collage through the series of iterations comprising Blow Up. And the poster format feels very democratic, which I love!

Obsessão is a massive collage, incorporating numerous images from my Ektachrome Archive series that were originally produced as smaller prints for sorting through the larger archive, so the poster makes that large collage more accessible. Unlike my other Blow Up works, Obsessão is more about the process of image editing—I love that it captures a particular moment in my thinking around the development of the Ektachrome Archive. At the same time it evokes various locales, for example, Gay Head (Aquinnah) on Martha’s Vineyard or Brazil, where it was originally produced on-site for the 32nd Bienal de São Paulo in 2016. While the larger, wall-mounted Obsessão collage has a distinct physical presence, there’s also a citational impulse that drives it. I’m happy the Obsessão poster offers BAR readers another way to engage closely with the work.

JJ: At the Rose Museum, viewers are invited to peer into vitrines, an installation tactic that is new for you, correct?

LAH: Yes, it’s the first time I’ve presented individual elements from my archive in this particular way.

JJ: And on the back of our poster, the descriptions run in a stream of text that allows a reader to dive as shallow or as deep as they desire. What was the process of researching, identifying, and/or illuminating the components of these pieces? Why does this feel like the appropriate time to render this work in this way?

LAH: Initially, producing and arranging all the elements of the original collage was deeply intuitive for me. Taken as a whole, it resulted in a massive visual cluster that engages viewers viscerally. To retrospectively map what had been spontaneously arranged in the larger-scale collage was a fascinating process—at times stressful but ultimately gratifying.

In a way, identifying the collage’s individual components allowed me to experience my archive in a new way. It enabled me to slow down, to reengage with it from different angles, and to do some fact checking. In the Ektachrome Archive, there are two dates associated with each image: One date records when I originally shot the photo and the other date identifies when I selected it for inclusion in the archive. (The second date was not identified on the poster because it treats these images as primary source materials, prior to their formal inclusion in the Ektachrome Archive.)

A similar process took place when selecting materials for the vitrines—taking into consideration their chronology as well as their associative meanings, which is intrinsic to collage-making. I’m thinking of Hannah Höch’s collage work of the early twentieth century. How do you unpack that process? For example, in art historical scholarship on works by Jasper Johns or Robert Rauschenberg, consideration is given to the tension between the creation of a specific work and the subsequent process of unpacking and contextualizing it. For me, engaging that tension is always exciting.

JJ: Documentation and archives are a mode for validating existence. Especially in Black and queer communities, archives can be like lifelines. What have archives meant to you?

LAH: Having an archive is important for any community, but each of us embodies multiple histories. I’m interested in mixing or playing with overlapping archives so that new narratives and storylines can emerge. For example, the Ektachrome Archive includes images of bell hooks, Martin Riggs, and Christina Sharpe spontaneously engaging in spheres of intimacy, which are very different from more well-known published photographs of them. I’m most interested in images that open up the possibilities of alternative readings.

Having previously deposited numerous Ektachrome slides and other photos I shot between the late 1980s and the early 2000s in my mother’s basement for safekeeping, I returned to the US in 2012 after having lived in Ghana intermittently over seven years. It was then that Isaac Julien inquired about using some photos from that earlier period in his MoMA catalog for “Ten Thousand Waves.” I subsequently began to engage more actively with the images that comprise the Ektachrome Archive, introducing them into new visual explorations and developing other narrative forms to think about family, collective community, desire, et cetera.

Getting back to Obsessão, that work serves to rupture my archive of images by placing them in juxtaposition with contemporary social imaginaries and other forms of discursive expression, such as newspaper clippings, to reveal resonances between the personal and the political that manifest in a broader, global context.

JJ: Let’s talk about patterns, textures, and collage. You’re a photographer who both finds and captures moments, but also a masterful creator who arranges, controls, and plays with what a photograph can be. How do you think about compositions and pairings in your work? How do you know when something works or when something just doesn’t?

LAH: My work is informed by my own intuition as well as by what I’m seeing or reading and the people that I’m engaging with. I usually cast a huge net in my thinking, then allow the intuitive act to bring together disparate images, texts, or patterns and mark making. But my intuition is definitely informed by a deep curiosity of looking and seeing and reading and researching.

There’s also the process of reconsidering the material elements, such as the printed Ghanaian fabrics in my Shadow Works series. After acquiring them it took eight years before I understood how these textiles might figure into my work. While participating in and documenting the funeral of my former Ghanaian partner’s Ashanti uncle, I was struck by the formality of the traditional grieving practices and their use of specific funerary fabrics. This led me to undertake further research as well as hold conversations with West African friends and curators to gain a better understanding of the cultural significance of these textiles and the symbolism of their printed motifs. The Rose exhibition exemplifies a curatorial framework that allows all of this to come together.

JJ: It was such a pleasure to meet your mother and your brother at the opening at the Rose. Their joy was radiant. In your art, we often see your chosen family from locations around the world paired with photos you’ve captured of your family or from your own family’s archive. What role has your family played in your work?

LAH: My practice has always been enriched by mixing my birth family with my family of choice. My relationship to photography is really informed by my grandfather, whose unique photo archive documented our family life from the 1940s through the 1980s. And there have always been others in my life who modeled what family could be, in particular my South African stepfather, who for many years was a freedom fighter against apartheid with the African National Congress and raised me and my brother in the Bronx in the late 1970s and early 1980s. There were always a lot of people around when I was growing up, as I was raised in the spirit of “the more the merrier,” especially for the holidays or special events.

Our lives are enriched by the presence of others. Even today, my brother and I continue to uphold our family tradition of hosting gatherings, bringing diverse people together. And just last week, on the occasion of speaking at the Tate Modern in London, I reconnected with dear friends who I consider to be among my chosen families, many of whom I first met in the late 1980s, and who influenced my evolution as an artist.

JJ: Thinking about all these places and people that have informed your work, I’m curious if place also informs how you show your work? Or maybe it’s more a question about how you think about audiences?

LAH: I think place is important and location—both literally and figuratively—has always informed my work. My work expresses my situated relationship to the various geographic, physical, emotional, or intellectual spaces in which I’ve lived, especially the Blow Up series. The fact that Obsessão was presented for the first time in Brazil definitely influenced how that work came together.

For instance, in the exhibition at the Rose Museum, visitors will find multiple locales represented in its vitrines—the Bronx, Los Angeles, London, Rome, Accra—globally mapping a spatial narrative arc represented by an early immunization card for travel to Tanzania in 1974, my Wesleyan University undergraduate student ID photos, formal portraits as well as postcards from artist friends Jim Hodges and Carrie Mae Weems, among other personal ephemera. Each item has a story to tell, suggesting a particular narrative thread to follow.

And I’m so pleased that my geographic narrative over the years includes Massachusetts in a big way, in particular, having had my works featured in several exciting exhibitions presented by the List Visual Arts Center at MIT, the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research in Cambridge, and in the “Dress Codes” exhibition at Boston’s ICA in 1993.

Nonetheless I think the current Rose Museum exhibition remains a standout, disrupting the linearity of a standard survey show to challenge received readings of my work while highlighting selections from my recent Shadow Works series. With at least a third of these works never having been presented publicly before, co-curators Caitlin Rubin and Lauren Haynes thought it important that “Our first and last love” offer a fresh take on the work I’ve produced over the last three decades, and provide the opportunity to unpack what it offers for the present, given the challenges facing all of us in the world today.