Boston’s ever-evolving public art installations are creating vibrant sites for civic dialogue, inspiring social interactions, and helping to build cultural and communal identity. Interdisciplinary artist Yu-Wen Wu is a fresh but significant contributor to this artistic territory. Her integrative practice is rooted in site-specific installation, video, drawing, text, research, and community engagement, often approached via methods of mapping, data visualization, and tracing conversations. She explores universal phenomena such as immigration (she is a Taiwanese immigrant herself), migration crises, environmental displacement, and climate change. Wu has a background in scientific research from her undergraduate studies at Brown University as well as in studio art, having taken RISD classes while at Brown and received her studio diploma from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

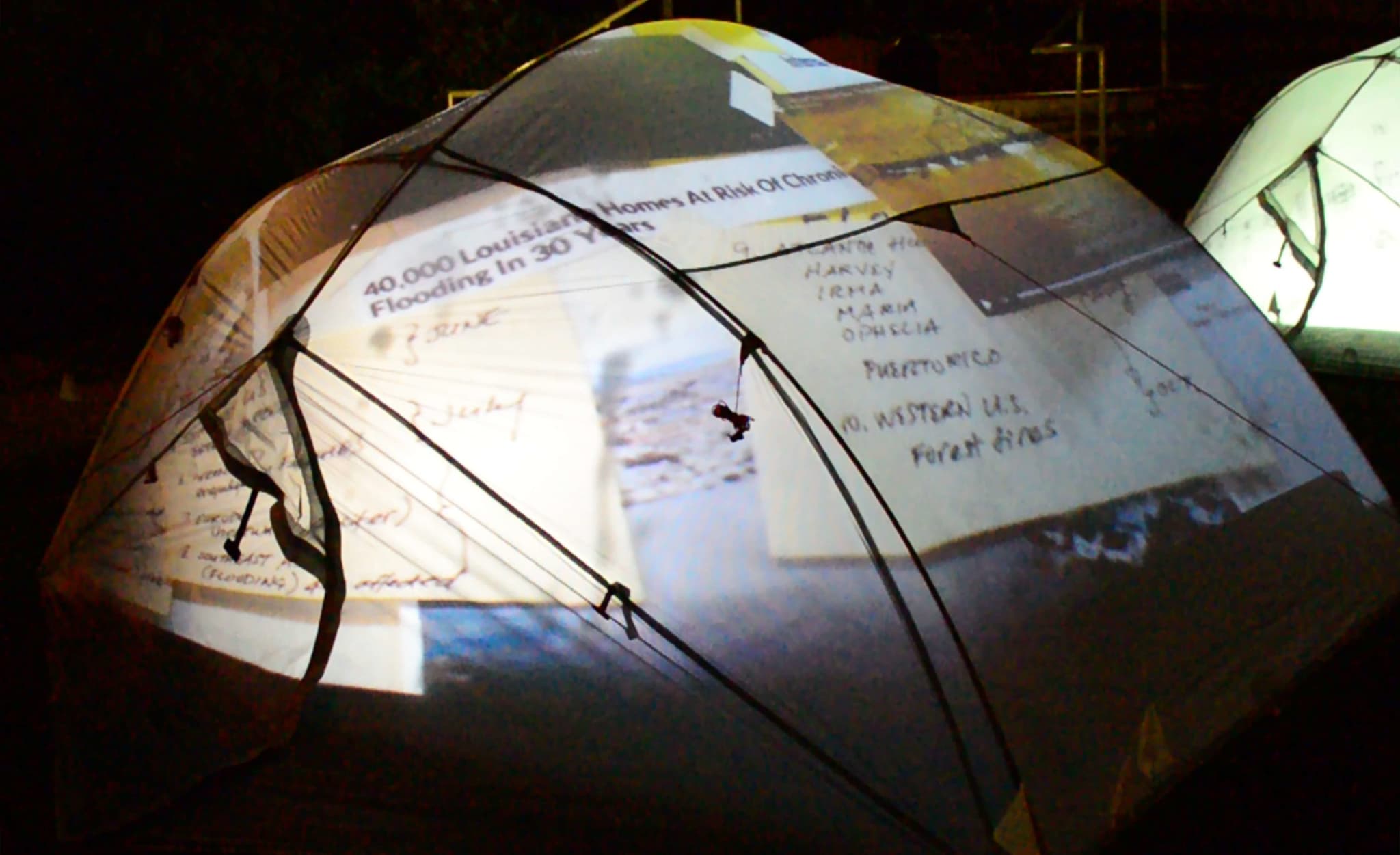

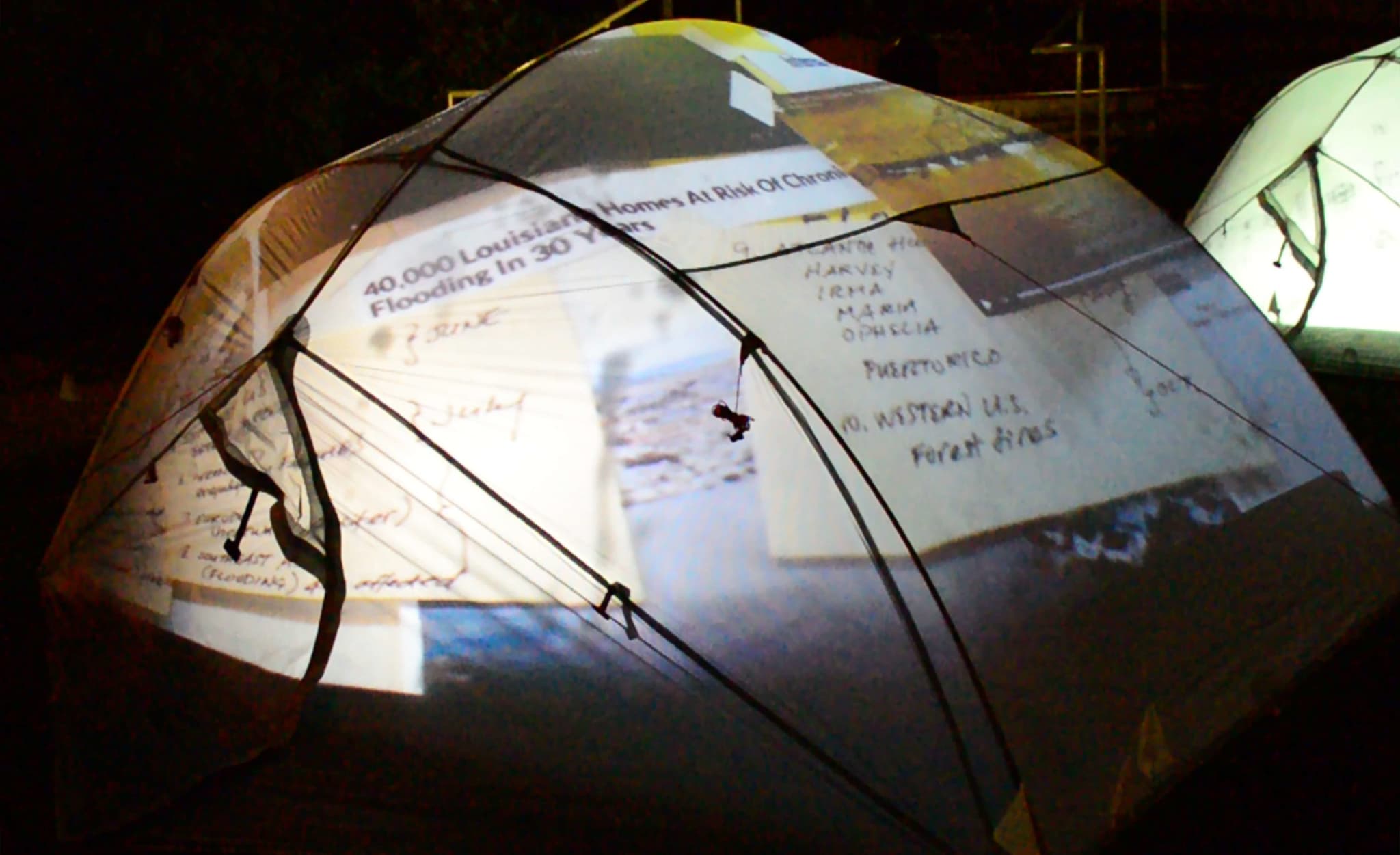

Throughout her career she has remained devoted to her meticulous drawings, making use of surfaces ranging from paper and canvas to entire walls. Effectively bridging the visual languages of science and art, these large-scale 2D and 3D works map sound, topography, walks, and other human routes, visualized via deconstructed line graphs, scatter plots, urban plans, and constellations. This practice carried over to Wu’s foray into video installation, where she started experimenting with stop-time animation and immersive, multimedia indoor experiences, such as her “High-Water Mark” (2019) installation at 3S Gallery in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Her first outdoor public art installation was “WITH/OUT WATER” (2018) at Boston’s Hudson Street Greenspace, which consisted of a five-channel video projection cast onto five shelter tents, initiating the dialogue between environmental change and community displacement that has become so central to Wu’s artistic agenda.

As the 2019 artist-in-residence at the Pao Arts Center in Boston’s Chinatown, Wu hosted community listening workshops as part of her ongoing “Leavings/Belongings” project (its fourth iteration is currently on view at SITE in Santa Fe as part of “Displaced: Contemporary Artists Confront the Global Refugee Crisis” through January 2021). For these sessions and throughout the project’s national iterations, she invites local immigrants, refugees, and other community members to craft symbolic cloth bundles. Each bundle embodies a participant’s complex and individual story; presented together, they serve as a collection of these stories. Over fifty workshops and several one-on-one interviews later, the impact of these gatherings is palpable in the sheer number of bundles, installations, and projects Wu has led. Currently, the artist has two major public art projects in development. The first of these projects,”LANTERN STORIES,” will be presented by the Rose Kennedy Greenway Conservancy and is set to open in late August 2020 at the Chinatown Gates in Chin Park. The second, which has been postponed due to COVID-19, will be the result of her participation in the Now + There Public Art Accelerator. I caught up with Wu to learn about the state of her practice, its intersection with public art, and the ideas she is churning for these ambitious projects.

Sketch for Lantern Stories, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

Gina Lindner: As a multidisciplinary artist working at the crossroads of art, science, politics, and cultural issues, what does your practice typically look like?

Yu-Wen Wu: My practice shifts from project to project and manifests in a variety of forms. But in every project, research is a large and significant component. This includes reaching out to community organizations and experts in a field, doing my own reading, and researching materials to use in the installation—because with public art in particular, it’s a big challenge for it to withstand all kinds of weather conditions. Aside from the research, there’s the community engagement element that’s really important to me throughout. I feel that if I’m creating art for the public realm, I need to hear the voices of the people occupying that place.

GL: What strikes me about your work is that regardless of the site, the public voice is always there. What has inspired you to shift your focus to large-scale, outdoor public art installations?

YW: Choosing the right site for my work is driven by a combination of the issues I want to address and the realistic constraints at hand. Considering who my audience is and who I want to reach is also a big deciding factor, because public art has the benefit of reaching a much larger and more diverse audience. But I don’t think I have to be a “studio artist” or a “public artist,” you know? These practices are not mutually exclusive, at least not for me, because my work in the studio—which includes drawing, sculpture, video, and photography—consistently informs my public artwork, and vice versa. Above all, I’d say that the work’s site is about the issue and how to take that issue to a particular public.

With “High-Water Mark,” a solo exhibition about environmental displacement, I was given this enormous gallery space in which I could create an immersive installation experience. I was able to project a 25-foot-wide video and make a 21-foot-tall drawing mapping the coastline of the predicted (rising) sea levels in 2030, 2050, and 2100. I also hung eighteen buoys from the ceiling at different elevations—I wanted the viewer to experience what it feels like to be physically under eighteen feet of water during a storm surge projected for 2100. What does that mean in respect to our bodies, or our homes? So these were effects that I couldn’t execute outdoors so well.

When I was awarded a grant by the Union of Concerned Scientists to create “WITH/OUT WATER”—which addresses severe climate changes and the environmental displacement of people—I wanted an outdoor site because that’s where I thought the conversation should take place. I wanted to talk about this issue specifically within Boston’s Chinatown community and locate the work on a site where Chinese and Syrian immigrants in the 1960s were displaced in order to build a highway and redraw district lines. The communities that are disenfranchised are often the communities that will suffer the most in the face of climate changes. What will happen in 2050 or 2100 when we’re faced with severe storm surges in urban landscapes never designed to absorb rising waters? And what happens when you don’t have the resources to move elsewhere? Contemporary art is not typically exhibited in Chinatown, so this public art installation gave an opportunity for people to think more critically about these issues.

GL: How do you anticipate that the public outdoor sites for your upcoming projects will help you communicate your ideas and actualize your community aspirations?

YW: Working with the Chinatown community on two previous large-scale projects has helped me understand what this community might want from a public art installation and, by extension, from my future Greenway public art installation in Chin Park. With this light-based installation, I want to embody the broader Asian culture and tradition, but not exactly replicate it. I’m very interested in the concept of light and what it means for the people of this community—especially because the artwork will be unveiled during the Chinatown fall lantern festival in Boston. Working with the concept of light is very abstract, and this has revealed for me one of the biggest challenges in creating public art: transforming an abstract idea into a physical encounter with art.

Earlier this year I hosted a community listening session at the Pao Arts Center for this project. We invited Chinatown residents, residents in adjacent neighborhoods and the general public. With this amazing turnout, I received some really wonderful feedback, all of which I’m in the process of collating right now. In the face of gentrification, it’s a tremendously challenging time for Chinatown residents, so it’s crucial to me to incorporate the community’s aspirations.

Leavings/Belongings, Installation view, Hubweek 2019: Foreign Born, Boston Based, Immigrant Led. 500 hundred Boston bundles, 6′ x 6′ cargo container. Image courtesy of the artist.

WITH/OUT WATER, installation view, One Greenway Park, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

GL: And what about your plan for the Now + There accelerator project? Has anything taken shape yet?

YW: I’m still finalizing the details, but I want to take “Leavings/Belongings” to a new chapter. In 2019 I was invited by HubWeek, Open Avenues, and New American Economy to participate in the festival’s forum titled “Foreign Born, Boston Based, Immigrant Led.” For this, I created an outdoor art installation of “Leavings/Belongings” consisting of five hundred community-made bundles and stories displayed within an open 6x6x6-foot cargo container. For the Now + There public artwork, I am considering a new iteration linking communities and mobility—stay tuned for more details.

GL: In my understanding, your personal experience immigrating from Taiwan and culturally assimilating in the US is something that compels you to represent the voices of immigrants in your work. Would you care to share any inspirations from your own immigration story?

YW: Yes, my subjectivity as an immigrant informs a lot in my work. I was about seven years old when I came to the United States. The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act enabled immigrants like my father to leave Taiwan—which was under martial law at the time—to pursue his master’s in engineering. It was a very difficult assimilation process for us: we spoke little English at first and there were no Mandarin- or Taiwanese-speaking families in our new “hometown” in New Jersey. But being in school helped me… I was very fortunate to have a wonderful first-grade teacher, who worked with me intensively every day to improve my vocabulary in English. Of course this was before the internet, and there were no organizations like the BCNC [Boston Chinatown Neighborhood Center], who do a lot to help immigrant families transition culturally and language-wise. I understand now how difficult it must have been for my parents, and for all new immigrants for that matter.

I’ve had many critical conversations about the immense challenges of assimilation, of identity, of dealing with racism and social inequities with participants in my “Leavings/Belongings” workshop sessions. From what I’ve gathered, there’s a common feeling of walking this fine line where you don’t really know. where you belong. Oftentimes you’re straddling both cultures. In assimilation, there are many traditions adapted or lost. And in assimilation, your cultural identity can be sacrificed, or worse, erased entirely… so how do you “belong” without also becoming invisible?

Leavings/Belongings, installation view, SITE, Santa Fe, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

Yu-Wen Wu and Harriet Bart with members of the Adelante Women’s Collective in Santa Fe, NM, creating cloth bundles for Leavings/Belongings (2019). Image courtesy of the artist.

GL: Given our current political climate of immigration pushback and your personal experience as an immigrant, what do you think people who are native-born in this country misunderstand about immigrant communities and experiences?

YW: There’s a lot of misunderstanding: there’s fear, and there’s a lack of knowledge about people who are immigrating to the States and why. This country is built on multiculturalism. Except for Indigenous peoples, none of our families are native to this country. When I invite local communities to the public “Leavings/Belongings” workshop sessions, they’re open to everyone who wants to share their stories of migration. Together we’re generating dialogues that bridge experiences, generations, ethnicities, and other social “borders,” creating a

platform for this massive accumulation of voices to be heard and to reiterate the extraordinary diversity of this country.

GL: Finally, what drove you to take on the Now + There Accelerator project? What do you enjoy about the program?

YW: It’s a great opportunity to learn the nuts and bolts of creating public art. When I did “WITH/OUT WATER” (an outdoor project) and “Leavings/Belongings” at the Pao Arts Center, my role as an artist was to design and fabricate the work. Someone else was taking care of permitting and other logistics. Now + There aims to provide the decision-making tools for artists to consider in making public art: budgeting, finding the right site, permitting, insurance, and bringing it to fruition. Most of all, the camaraderie of the cohort provides wonderful friendship and support.

________________________________________________

See Yu-Wen Wu’s “Bundle Stories” (2019) on the cover of Issue 05: No Boundaries and learn more about her work and upcoming projects on her website, www.yuwenwu.com.