Danielle Abrams’s performances are as poignant as they are humorous, drawing from her queer, Black, and Jewish identities she creates and per-forms characters that illuminate the myths and entanglements of being biracial in the United States. In her work, she has embodied figures as wide-ranging as her Black grandmother from the South, her Jewish bubbe from Queens, various members of the Black Panther Party, and the fictitious Black ballerina Eleanora Antinova. Out of character, speaking in the plush baritone and muted r’s of her natural New York accent, Danielle is both contemplative and charming, and just as spellbinding as those that she personifies. We met when I was a graduate student at SMFA at Tufts, where she is a professor of performance.

When Danielle visited my studio to discuss my work over Cuban coffee, we began a conversation that continues to this day. In the years since I’ve graduated, we’ve worked together as artist and curator on multiple occasions, and our initial relationship as professor and student has evolved to that of friend and collaborator. Most recently, I curated a series of virtual performances for the inaugural Area Code Art Fair last June and enlisted Danielle to perform Great (2020), a monologue developed specifically for the fair. Delivered from her kitchen table, the work traces the history of a Black family that migrated from Virginia to New York in the 1940s, the matriarch of which is, presumably, her great-grandmother. Months later, Danielle and I discussed why language matters, our current projects online and IRL, and our vision for what lies ahead for the United States.

Introduction by Gabriel Sosa

Danielle Abrams, GREAT, 2020. YouTube live performance. Photos by Willoughby Hastings. Courtesy of the artist.

Gabriel Sosa: I recently rewatched Great, in which you play a fictionalized version of yourself recalling childhood experiences when you’d shuttle between the Jewish and Black sides of your family. You revisit that wide-eyed wonderment of childhood with the critical, cautious eye of an adult. I was reminded of how you both savor and scrutinize the hybridity that defines so much of your work. Why is that?

Danielle Abrams: “Savoring” and “scrutinizing” hybridity! I’ve always had a hard time with binaries. Perhaps this is a consequence of the hypocrisy that comes with growing up [biracial], where what is lived does not conform to the dominant ideology, which relies upon essentialism and the bifurcation of identity.

Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 legalized the segregation of Blacks and whites in the South. Segregation has left tracks in today’s dirt, whether pertaining to employment, academia, healthcare, home and business ownership, or recreation. Who has the “right to breathe” is another vestige of Jim Crow. Oxygen is an entitlement that is still denied African Americans, whether by police brutality or through substandard medical care for COVID-19.

My light “passing” skin defies the assumptions that society uses to legitimate racial hierarchy. I’ve spent my life vacillating between white, Jewish, and Black access, privileges, speech, and cultural codes. Because of my racial ambiguity, I frequently bear witness to racism and anti-Semitism. I am grateful for this evidence. It is fodder for my work.

In terms of linguistic ambivalence—particularly in the courts—I’d like to hear more from you. Your work distorts the legibility of legal language. You also defy its presumed discretion by presenting transcripts at an oversized scale. Legal rhetoric itself is implicated in your work, in lieu of the defendant. How does this recontextualization of the language serve to change people’s lives, as the courts purport to do?

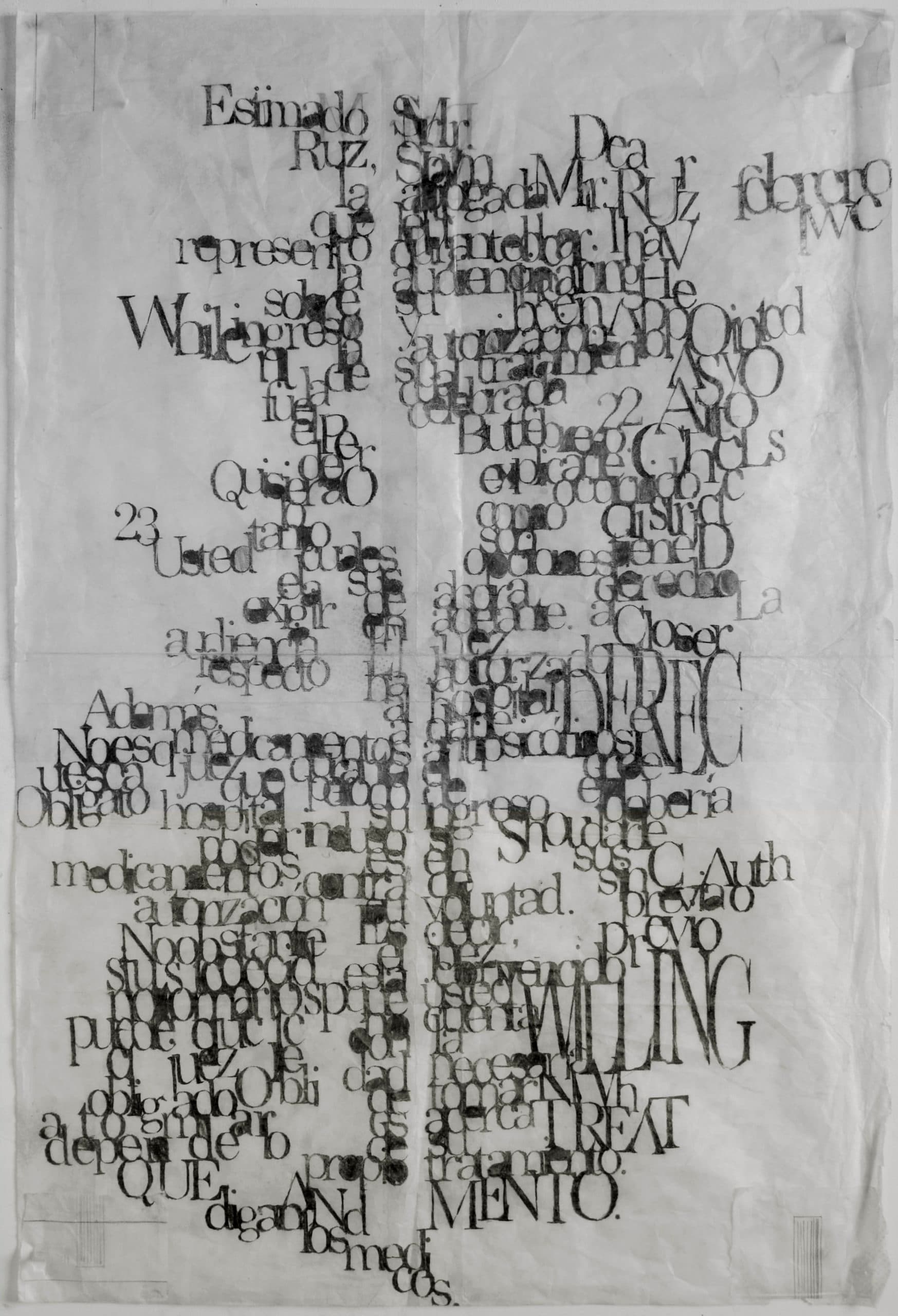

Gabriel Sosa, A Memo for Mr. Ruz, 2019. Graphite on paper, 25 x 37 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist.

GS: Right, so much of the language I encounter as a court interpreter informs my artwork, whether it’s the legalese of a court order or an emotional testimony. A lot of this language is routine, rendered generally unremarkable to those who utter it on a daily basis. Moving that language from the courtroom and into a drawing or video piece completely transforms it—almost like the colors in Josef Albers’s exercises. Context is everything. I’m not sure that recontextualization alone changes any lives, but I hope that it gets a conversation started. In fact, you and I share a love of recontextualizing language. In Great, there’s a scene where you shake Tabasco sauce onto a three- dimensional paper cutout of a plate of home-cooked food, soaking yourself in the process, all while you exclaim and repeat the words “liquor, food, joy.” Can you talk about what went into that?

DA: When we’d go to my Aunt Margaret’s house, I learned how to be Black. I know that sounds peculiar, but what I mean is that I learned about Black culture, as distinguished from what was already dominant in my upbringing—white secular Jewishness. Food, which is always the residue of ethnic and cultural identity, was one of my first tastes of a divided identity. Although it was all delicious, bagels, lox, and pot roast were extremely different from the fried chicken, chitterlings, and collard greens covered in hot sauce and cooked by my aunts and great grandmothers who came from the South.

Pouring that hot sauce all over my chest and having it drip down my legs made me feel Black “joy.” However, I was of two minds. While feeling the spicy wetness penetrate my chest and body, I connected the blood red sauce to excessive bullets penetrating the flesh of Black bodies. The hot sauce bottle was a pistol, with each shake shooting splashes of blood into my Black chest. The hot sauce united my identities and built a bridge between life and death. It was a salve for healing.

Your project No es fácil/It Ain’t Easy (2020–21) is also a kind of salve. I wonder if you could talk about reaching for happiness, self-care, self-love, faith in this moment. When you made the billboards that read “No es Fácil, Pero Tú Tranqui” or “It Ain’t Easy, But Keep Going,” I had the sense that you were speaking about the confluence of stresses that particularly affect communities of color—our former presidential administration, white supremacist law enforcement, and COVID-19. In regard to healing, how do your billboards intervene upon the communities in which they are installed?

Gabriel Sosa crosses the street in front of a billboard part of his No es fácil/It Ain’t Easy series, 2020. Installation view, Roslindale Square, August 2020. Photo by Iaritza Menjívar.

GS: The billboards are located in neighborhoods that have been most affected by the pandemic, with high concentrations of immigrants, and thus lots of essential workers, including East Boston, Dorchester, and Roxbury—neighbor-hoody areas with laundromats, cell phone stores, panaderías, and lots of pedestrians. The featured phrases are intentionally ambiguous, meant to offer solidarity in a difficult moment, whether on a personal or social scale. They also oscillate between a ramping up and a slowing down; “No es fácil, pero no te desesperes” (It ain’t easy, but don’t despair) in East Boston was followed by “It ain’t easy, but keep going” in Roslindale, so in this sense, simultaneously questioning and offering different ways to respond to adversity. Our friend-ship has given me a deeper appreciation for the meatiness of words—how they are written, spoken, pronounced, chewed up, and spit out. Can you talk a bit about where this comes from for you?

DA: One of the greatest weapons that African Americans have cultivated is wordplay—signifyin’. Rebuilding language can slay a beast. Language is a window into the soul, and I have an internal vault with the expressions, accents, chides, throat clearings, and curses of everyone with whom I engage. I love to mimic the Southern accents of my family. I also rotate my palette to speak “Jewish jazz.” As a Catskills “Borscht Belt” comedian in Routine (2008–2017), I perform as a mid-century Jewish comedian while delivering a barrage of sexist and self-deprecating jokes, many of which have now become associated with TV movies, sitcoms, and stereotyped Jewish characters.

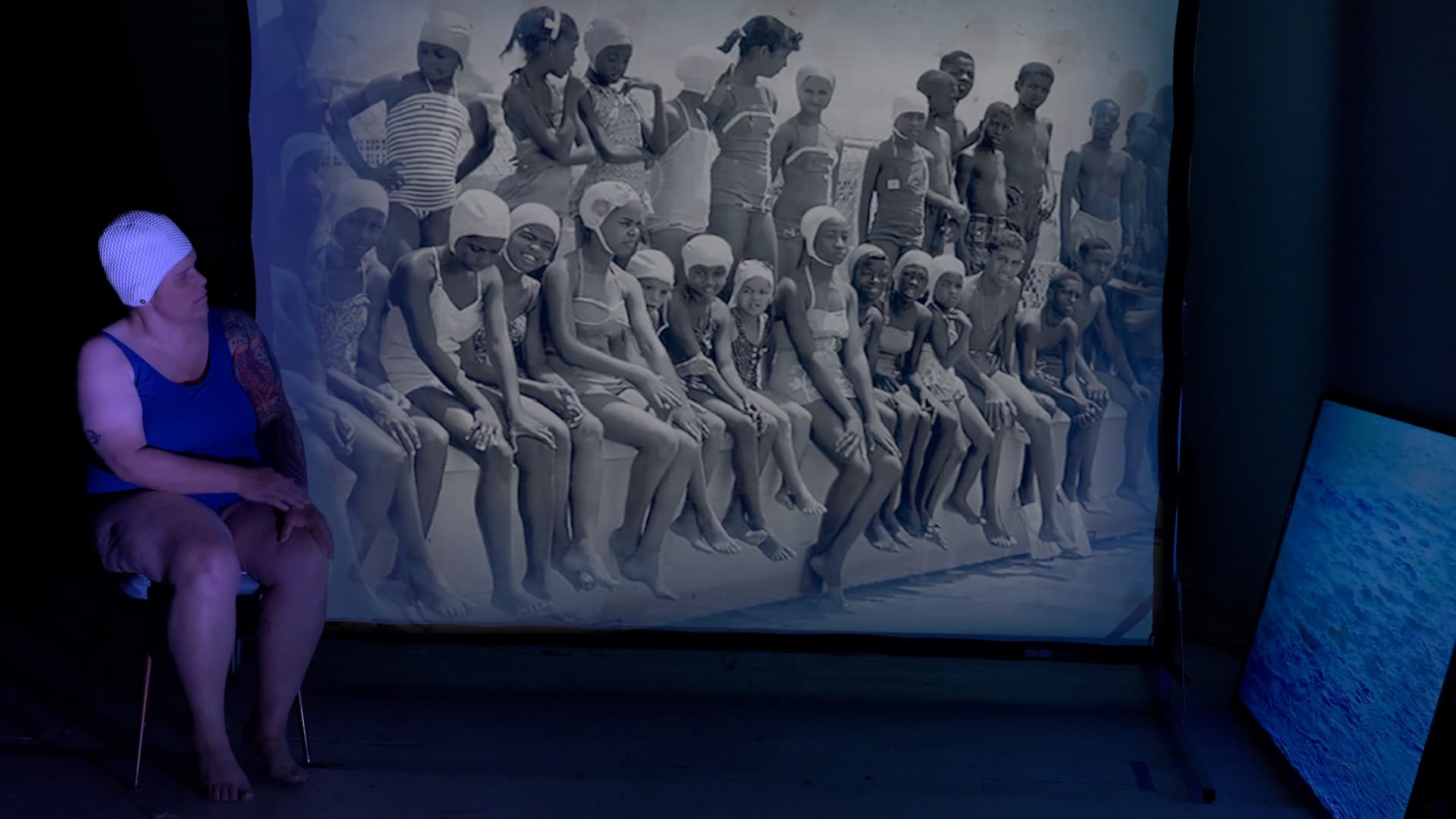

Danielle Abrams and Mary Ellen Strom, LINCOLN GAVE US A BEACH with Honora Carlson-Strom, 2020. Photo courtesy of the artist.

GS: The night after Biden’s victory, I watched you perform LINCOLN GAVE US A BEACH (2020), a collaborative piece with Mary Ellen Strom about a once-segregated beach in New Orleans. Watching it was a sobering but motivating reminder of the work that lies ahead.

DA: It was fascinating to perform on a day it felt like the world was on full tilt. This has been such a topsy-turvy era, one in which we’ve seen unprecedented cruelty, global and national instability, and blatant disregard for our environment. The fear and rage I’ve felt disfigures the imagination. Consequently, some of the language in LINCOLN GAVE US A BEACH is spoken backwards. The words refer to New Orleans’s culture, segregation, and Lincoln Beach’s plant life. They are projected on the screen as “ROLLERCOASTER,” “LEVEE,” “PO’ BOY,” “LIVE OAK TREES,” et cetera. Reading them aloud and in reverse en-ables an alternate language, one that signifies the vernacular that was, and is, crucial for Blacks to use in a post-Jim Crow society. Backwards language can also be prophetic. For instance, the word “DROWN,” which appears on the screen, is “N-WORD” when reversed. Drowning is the fate of many Black people who are kept from safe swimming conditions. Tinkering with language spells out veiled truths and some-times tells us what we need to know.

GS: Do you have any hopes for how language can be used and valued in the Biden administration?

DA: May our forthcoming leadership deploy language creatively as a means of reforming the xenophobic and dangerous ideologies that have become both celebrated and protested. I am hopeful, relieved, and in this moment, revel in the national street parties—everyone masked and dancing with their neighbors. There I see a profound sense of freedom, bodies celebrating and collectively gyrating in public spaces during a pandemic. And once we stop dancing, it’s time to rewrite the United States.