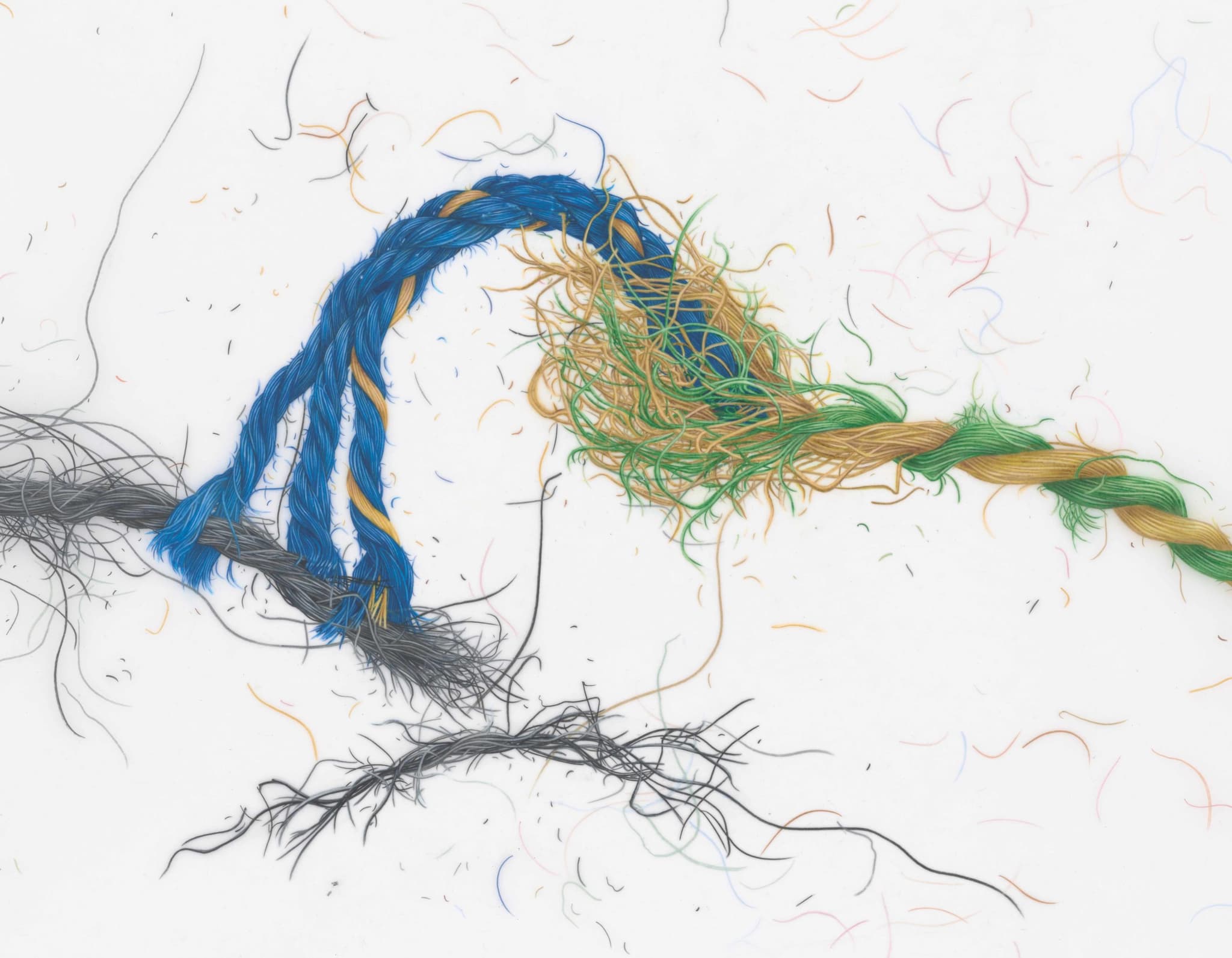

“Attention,” the poet Mary Oliver wrote, “is the beginning of devotion.” It’s also the starting point for Evelyn Rydz, a multidisciplinary artist whose diverse creative practice—which includes drawing, photography, site-responsive installations, and participatory community projects that bring people together in person and online—is grounded by a commitment to close attention as a form of care and a means for connection. It’s evident in everything from her unique dinner parties, designed to foster deep listening and meaningful conversation, to her field studies of coastlines, which often have her peering through jewelers’ glasses and microscopes at manmade detritus that washes ashore. “Water has always been at the core of my interest and curiosity, from childhood all the way to now,” says Rydz, who grew up surrounded by water in Miami—in fact, her very first word was agua. “As a first-generation American with parents who were born in Cuba and Colombia, and grandparents who escaped Poland during World War II, I’m really interested in thinking of water in terms of relocation across coasts and how we’re shaped by those different coastlines and their relationship to home. Water is about distance and separation, but it’s also the thing that connects different places.” Rydz experienced her own relocation in 2002 when she moved to Boston to earn her MFA at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. Right away, she missed the omnipresence of the ocean she’d felt keenly in Florida. “Even though we’re on the coast here, it’s so different,” Rydz says. “So I started trying to build a new relationship to a different body of water.” She began taking long walks on New England coastlines, from Boston-area beaches to the rocky shores of Maine, and noticing debris spit out by the surf. She observed how an object like an orange bottle cap might become camouflaged in its new context, almost resembling a piece of coral after years of being sculpted by the waves. “My curiosity slowly crystallized into concern,” Rydz explains. “I became really interested in these cycles. What was washing up so often was plastic, and its long history could be traced to an ancient zooplankton dying, going to the depths of the ocean, and then becoming fossil fuel and being molded and shaped into plastic toys and tools to use on land, which often end up as fragments of debris back in the ocean and could cycle in currents for three or four years, then wash ashore on coasts all over the globe.” These mass-produced, quickly discarded commodities are exposed and transformed by Rydz’s careful observation and painstaking handcraft—slow, intentional processes that subvert rapid cycles of capitalist consumption. The resulting works make microscopic processes visible and big concepts easier to fathom. In her Unraveling series, for instance, colored-pencil drawings of frayed marine ropes render individual synthetic fibers in photorealistic detail, while the ongoing project Coastline has Rydz splicing such rope fragments together into a single horizon line. “My goal,” she says, “is to make 372 of them across different panels to represent the estimated 372,000 miles of global coastline.”

Evelyn Rydz, Unraveling, #7, 2019. Colored pencil. 11″ x 14″. Photo by Stewart Clements.

Many of Rydz’s water-related works have invited viewers to become participants, to collaborate as fellow researchers and creators. Floating Artifacts, a series featuring magnified portraits of minuscule pieces of plastic, allowed gallery-goers at Tufts’ Aidekman Arts Center to peer at specimens under a microscope and use typewriters to record their own observations on index cards. Her project Salty > Sour Seas had ICA visitors investigating ocean acidification by pH testing and painting with water samples from Boston Harbor—and by taste testing sour popsicles made with lime juice, Atlantic sea salt, and phytoplankton (the vital and vulnerable algae that form the base of aquatic food chains and produce half the atmosphere’s oxygen). “I wanted people to consume something unexpected,” Rydz explains. “I think food can be such a connection to memory and to remembering an experience.” The link between food and memory is at the heart of Comida Casera, an intimate event series that’s pushed the participatory ethos of Rydz’s practice even further. The name of the project translates to “homemade food,” and participants are asked to bring a dish inspired by a woman who gives them a sense of home. Rydz curates the guest list, gathering women from a wide range of backgrounds and ages for a social experiment that catalyzes moments of connection. “You’re sitting with strangers, which can seem a little strange, maybe uncomfortable at first,” she says. “But then the night begins.” At this anything-but-average dinner party, the first course might well be dessert. Rydz usually starts the meal by sharing the story behind her own dish—say, a bread pudding inspired by her mother, made with challah and layers of guava. “My mom makes this challah bread pudding that feels like a connection to her parents, and the guava is a connection to my parents, who have a guava tree in their backyard,” Rydz explains. “I talk a little bit about her and her generosity and the warmth of this bread, the smell . . . it’s a real comfort dish that reminds me of home. It also reminds me of her resourcefulness: nothing goes to waste in her house.”

Memories were on the menu at a 2018 Comida Casera gathering at Cambridge’s Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African & African American Art. Photo by Mel Taing.

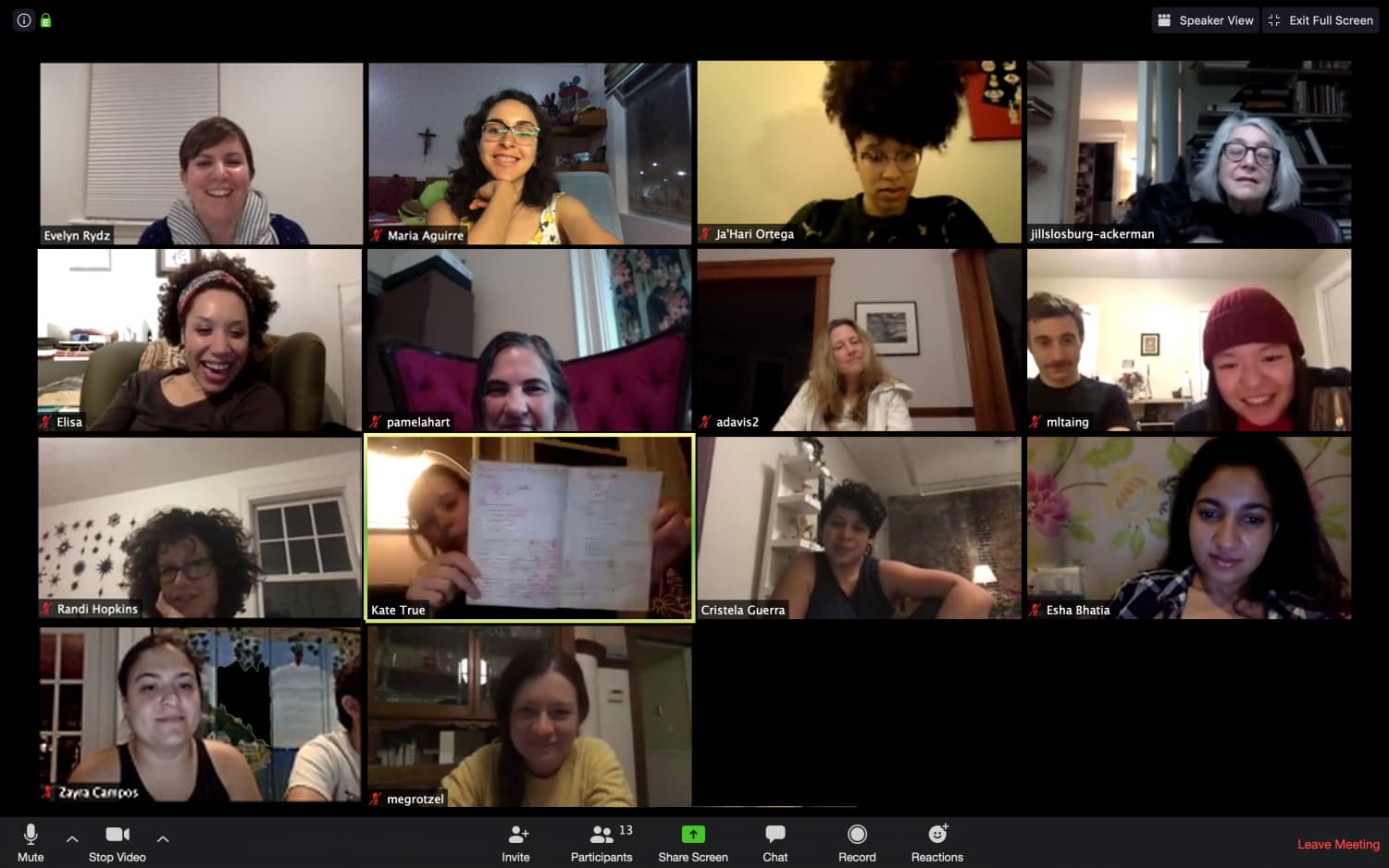

After sharing the story behind the recipe, she passes her dish to her neighbor, and it moves around the table, hand to hand, so everyone can try a taste. Then the other guests take their turns, sharing memories of mothers and mentors, aunts and grandmothers, friends and lovers. “The food, of course, tastes so much better after you’ve just heard this story about this grandmother or somebody’s best friend,” Rydz says. Drawn from all over the world, the dishes offer a smorgasbord of different flavors and cultures, but plenty of parallels too. Rydz remembers one dinner where two participants brought plantains, a staple in many cuisines. One spoke of her Nigerian mother, who prepared plantains every day for a month when she was recovering from the birth of her first child; the other recalled the patience and care of her Venezuelan grandmother, who always waited for just-right ripeness and sliced the starchy fruit into precise slivers for a perfect crisp. This isn’t standard small talk. Rydz recognizes that food can be a portal to the past, a conduit of culture, an expression of love. The prompt is designed to be personal, to cut through the default “So what do you do?” inquiry. “People aren’t talking about where they work or what they do or their titles. They’re sharing something really meaningful about where they come from or what they think of as home,” she says. “Part of why I started the project was really about creating a community that could transcend divides, to use the table as the site for gathering, for open exchange, for active listening, for celebrating differences and at the same time finding so much common ground.” Since Rydz hosted the first dinner in her backyard in 2016, hundreds of women have gathered at museums, galleries, universities, and other locations for Comida Casera events, often documented with imagery by local photographer Mel Taing and audio recordings of participants’ stories. The project has grown beyond the dinners with offshoots like Aquí y allá: juntos a la mesa, a 2019 installation at the ICA’s Watershed, where programs co-hosted by Rydz and Eastie Farm’s Kannan Thiruvengadam took place around a communal table of Rydz’s design, complete with fragrant herbs bursting through cracks in its surface. And since the COVID-19 pandemic, the project has been reimagined on Zoom, where Rydz hosts Recetas de Casa, a healing recipe exchange that’s drawn participants in Boston as well as New York, Miami, Mumbai, and Guayaquil, Ecuador. “I love that it’s able to bring together people across differ-ent time zones and different places, which would not have been able to happen in person,” she says.

In the summer of 2019, visitors to the ICA’s Watershed listened to stories recorded at Comida Casera events and participated in activities at Rydz’s table for Aquí y allá: juntos a la mesa. Photo by Mel Taing.

Recetas de Casa isn’t the only community project Rydz has created during the pandemic. A few days after the death of George Floyd, she wrote a letter to her students at MassArt, where she teaches drawing in the studio foundation department. “The letter basically said, I am in this with you. I’m here for you if you need to talk. And I understand that you’re home, it’s a pandemic, we’re witnessing all kinds of racial injustice, and we’re all feeling restless and burdened and concerned,” Rydz recalls. “I wanted to take a moment to tell students that they could use that sense of urgency. . . . How could they respond to what they were witnessing and use their creative tools to synthesize all this information and at the same time to envision something different, to imagine a different future?” That question served as the springboard for Drawing on Love and Justice, a project that’s invited artists to use their powers of observation and imagination to create drawings that address what they see in the world now and what they want to see in the future. “I realized it doesn’t just have to be a class or student project; this can be opened up to a larger artist community,” Rydz explains. She partnered with the MIT List Visual Arts Center, hosted Zoom workshops with the ICA and the MassArt Art Museum, and put the call for participation out on Instagram, welcoming drawings in any medium through election day. The scores of participants in the resulting exhibition-by-hashtag ranged from seven-year-olds to college students to established local artists like Taylor Davis, Gonzalo Fuenmayor, and Dell Hamilton.

Since the pandemic, Recetas de Casa has allowed participants to share stories and recipes online.

“There’s such a range of participation,” Rydz says. “I love what artists do, which is just show a complete range of responses, from figurative to abstract, some more playful and others much more serious, and such a huge range of issues and concerns, things people are thinking about, things that give them pause. I love that the visual tone of voice has a real range.” Rydz’s own practice is distinguished by its expansive range, yet there are clear throughlines, too. ”Whether it’s through my drawing practice and the kind of care that comes through close observation and careful handcraft and making, or through popsicle tasting or painting on pH paper with river water, I love having people be actively involved in looking and making together,” Rydz says. “I’m thinking a lot about care: what we care about, what we care for, who we care for, and how active caring is a really important part of building community.”

Evelyn Rydz’s Drawing on Love and Justice project has taken on a new life in a partnership with the Cooper Gallery at Harvard titled The Sketchbook Collective. New prompts for daily drawing practices are released bi-weekly. Each week, participants are invited to share their drawings with the community. On April 14, Rydz will present an artist talk with On Belonging In Outdoor Spaces.