Issue 06 • Feb 27, 2021

“Wayfinding” Exhibition Expands the Critical Possibilities of Historical Maps

Shana Dumont Garr Reviews Wayfinding: Contemporary Artists, Critical Dialogues, and the Sidney R. Knafel Map Collection at the Addison Gallery for Issue 06.

Review by Shana Garr

Heidi Whitman, installation view, New World, 2019–20. Ink, gouache, acrylic, imitation gold leaf, canvas, cloth, gauze, paper, Cinefoil, string, rope, Duralar, and wire. © Heidi Whitman. Courtesy of the artist.

Heidi Whitman, installation view, New World, 2019–20. Ink, gouache, acrylic, imitation gold leaf, canvas, cloth, gauze, paper, Cinefoil, string, rope, Duralar, and wire. © Heidi Whitman. Courtesy of the artist.

Maps externalize the European imagination regarding landscape and have been tools of colonization for centuries. The desire to represent the earth’s surface in a declarative way, inferring an all-encompassing understanding of what is there, is not a universal ethos. Other cultures allow for sustained mystery, animism, and yielding, wherein the land is not inert, but rather living, with the capacity to collaborate with all animals, including humans.

Imaginative ways of representing the land are on view at the Addison Gallery of American Art at Phillips Academy in Andover in “Wayfinding: Contemporary Artists, Critical Dialogues, and the Sidney R. Knafel Map Collection,” an exhibition in which six artists, both regional and from other parts of North America, worked for two years in response to an eminent collection of historical maps. As primary sources from prior centuries, the maps are striking visual objects and documents of economic and political priorities of the fifteenth to nineteenth centuries, but the exhibition prioritizes the contemporary artistic responses.

Displayed across three galleries, the artists’ works unite in their shared inspiration and their sound grasp of our present time, but otherwise look quite different and do not overlap in gestures toward collaboration. The contrasting styles, mediums, and moods and different cultural backgrounds of featured artists Sonny Assu, Andrea Chung, Liz Collins, Spencer Finch, Josh T. Franco, and Heidi Whitman indicate a curatorial effort to shepherd forth a polyculture, reflective of a wider societal reckoning with Eurocentrism. Traveling to an art gallery, let alone another state, is now somewhat of a feat during the pandemic, making “Wayfinding” an enjoyable exhibition to visit because it provides the subject matter of trekking and hints of the immersion and slippage of time as intensive observations of history, the present, and hopes for the future coexist.

The eighty-eight maps, globes, and atlases in the Knafel collection were made between 1434 and 1865 and are held at Phillips Academy’s Oliver Wendell Holmes Library. This is a great time to revisit the subject, as critiques of colonization of the Americas—including the June “beheading” of a Christopher Columbus sculpture in Boston’s North End—are quite timely and pointed. The Knafel collection was last roundly highlighted nearly thirty years ago with Thomas Suarez’s 1992 book Shedding the Veil: Mapping the European Discovery of America and the World, which marked the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s voyage. In “Wayfinding,” the artists’ commentary ranges from overt criticism to open-ended aesthetic revelry.

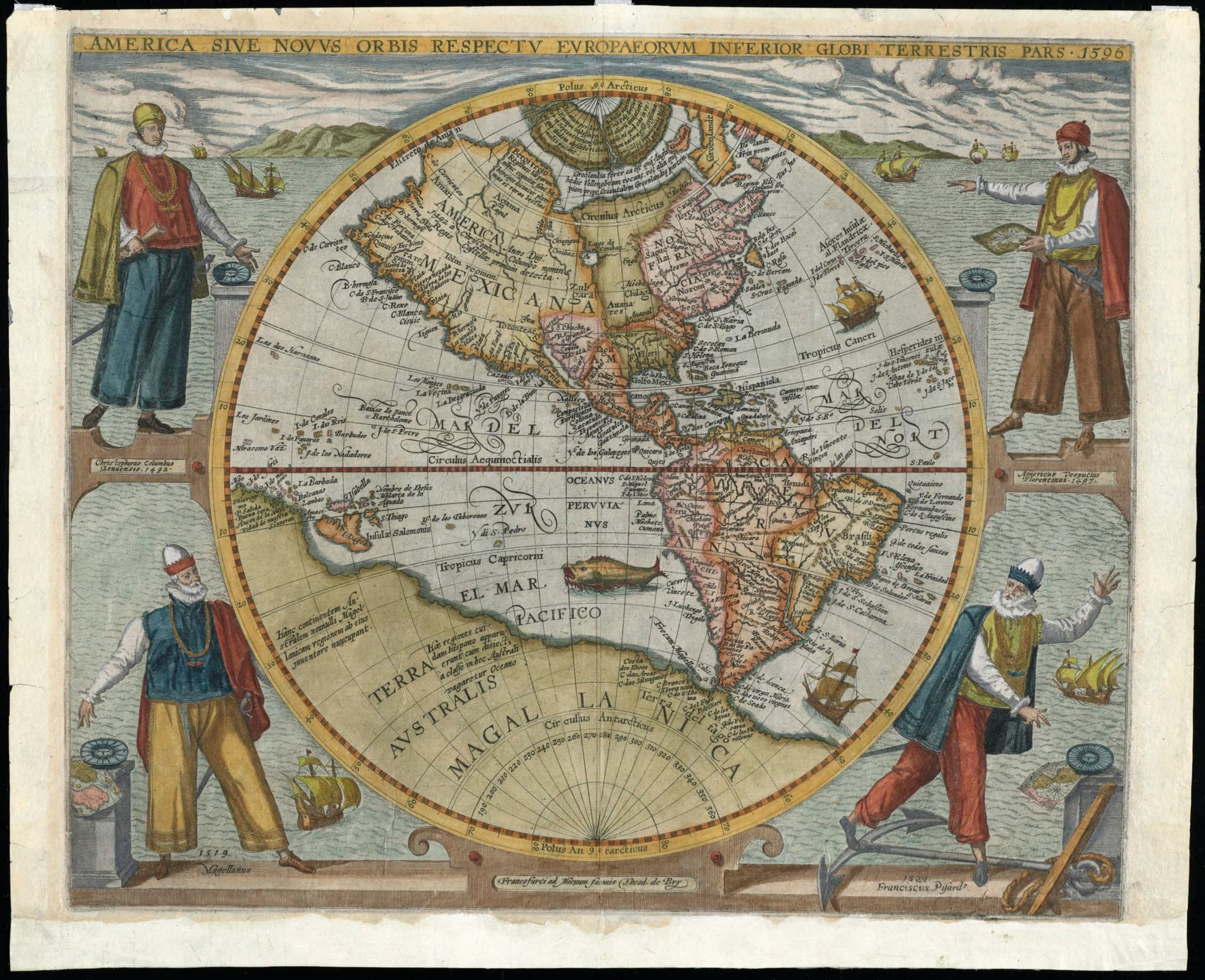

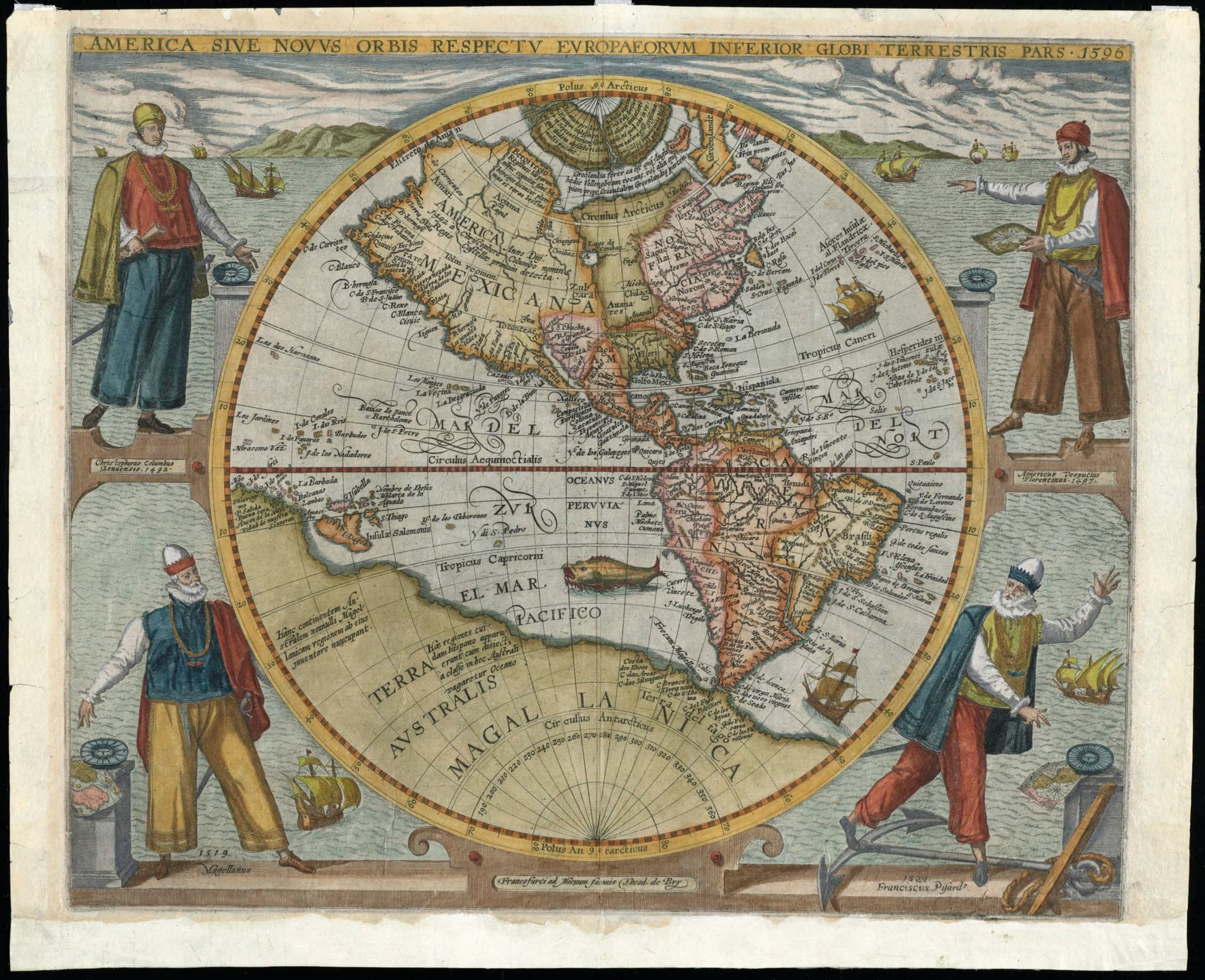

Theodor de Bry, America sive novus orbis respectu Europaeorum inferior globi terrestris pars, 1596. Copperplate engraving. 11” x 11”. Courtesy Addison Gallery of American Art.

The densely hung historical maps date mostly from the seventeenth century on a title wall, where an exhibition introduction acknowledges that the maps document a European understanding of the world. To the upper left, a 1677 map of New England by John Foster shows an unusual view of Massachusetts looking directly over the length of the commonwealth with the bay in the foreground. Five ships appear much larger in this perspective than points inland. The Indigenous territories Narragansett and Nipmuc appear with historical spellings alongside current cities such as Springfield, Concord, and Woburn. The maps’ variances from contemporary representations make them appear subjective rather than factual.

Andrea Chung, an American artist of Jamaican, Chinese, and Trinidadian descent based in San Diego, had the most self-contained and haunting response to these maps. Her work The Westerlies: Prevailing the Winds is a dome covered with cyanotype on cotton, creating an inviting yet stark stage set for an individual to contemplate an imagined seascape at night. An empty little white boat with oars rests to the right. Suddenly, a friendly and mysterious disembodied whisper sounds through the dome, and we might infer that is a warning from the ocean and the sky. Knowing exact boundaries, this work implies, is overrated, and different priorities enable a familial, protective connection with homelands.

Nearby, Sonny Assu’s work is at first unassuming, yet delivers a poignant and memorable message. Assu’s heritage is Ligwilda’xw of the Kwakwaka’wakw nations, an Indigenous group that occupies the mid-northeastern coast of Vancouver Island and the adjacent mainland of British Columbia. Assu now lives in the unceded traditional territory of his ancestors. Two pinball machines titled Landback and Look at What I Columbused 2 stand beside each other, with no accompanying adornments or setting. The “games” take the same shape as the machines in arcades, but the screens, though blinking and vibrantly lit, are blank, the sleek wood surfaces of the cabinets unpainted. Typical arcade games blare with sound, animated figures, and the promise of points—if you put money into it and play the game well according to the rules, of course. Landback and Columbused refuse to offer the means to play. There are no characters, themes, or courses of action. Metaphorically, what is missing is the same attitude and data one finds in a map. Assu utilizes a familiar trapping of Western culture, a video game, to express an Indigenous unwillingness to reduce the concept of land to a thing that could be stolen.

Opposite Chung and Assu’s works in the same gallery is a grand, colorful installation by Liz Collins, an American artist of European descent who lives in Brooklyn. Collins’s Atlas Matrix Variation series is a tour de force. Though wide-ranging, the works are effortlessly in sync and thoughtful in their use of historical maps as muse. The central installation, Stretched Markers, made with woven silk yardage, simultaneously evokes a flag, a dress, a maze, and a banner, its complexity persistently demanding one’s gaze. In red, white, and blue, it could be read as a response to a map’s key or legend, but it transcends these while also suggesting a kaleidoscopic renovation of the American flag.

Andrea Chung, The Westerlies: Prevailing the Winds, 2020. Steel pipe, Plexiglass, cyanotype on cotton. © Andrea Chung. Courtesy of the artist and Klowden Mann. Photos by Frank E. Graham.

Sonny Assu, Look at What I Columbused 2 and Landback from Insert Coin, 2020. Arcade cabinets (maple plywood, screen, electronic components), copper paint, Mylar, adhesive vinyl, and 10-second video loop © Sonny Assu. Courtesy of the artist and Equinox Gallery.

The most refreshingly disruptive of the offerings, particularly in the formal setting of the Addison Gallery, is an immersive reading room entitled SNAKE ATLAS (serpent lightning leads to water; for my father who was bitten, so that rattler also resides in me) by Josh T. Franco, a Chicano and Texan who currently lives in Maryland. The room has a warm and abundant feel accentuated by an upbeat, rollicking sonic land-scape made for the installation by ambient/experimental musician Chad Turner. The stimulating combination of materials includes handprints upon corn husks, art historical quotes upon a painted grid of 35mm projector slides, and even a rattlesnake head in a jar (an artwork by Robert Smithson) on a shelf flanked by pieces of gold quartz and golden obsidian. In an elaborate, map-like drawing, a handwritten passage from Cormac McCarthy’s 1985 novel Blood Meridian encompasses the pictograph of a horse and rider, further bordered by engaging marginalia, including a phrase that is part of the work’s title, “fuck the Judge.” The star of the room is a large snake sculpture made with thousands of multicolored marble chips. Snakes traditionally lead desert peoples to water, so sighting one would be of more use than a map. It is the only work in the exhibition to refer directly to the earth by bringing pieces of it inside and placing them back upon the ground.

The next gallery features a classic “white cube” presentation by Spencer Finch, an American artist of European descent based in Brooklyn. Moving between his and Franco’s spaces is a pleasure because it recalls walking from one gallery to another in Manhattan, with a shift between two intriguing but contrasting moods. Finch’s works dive into color in a conceptual, minimalist manner. One series captures the colors of items observed on hikes, each item (grass, tree, crow) noted by hand beside Pantone swatches presumably chosen with considered specificity. A standout, the series Studies for Paths Through the Studio, is a stacked hanging of five pastel paintings on paper. Signed by the artist in January 2020, they are prescient about a then-looming pandemic, where one’s interior becomes memorized as we experience quarantine. Each beautifully zig-zagging shape has a different color, and as a composite they are random, personal, and touchingly specific.

Josh T. Franco, SNAKE ATLAS (serpent lightning leads to water; for my father who was bitten, so that rattler also resides in me), 2018–20. Mixed media and multimodal installation. © Josh T. Franco. Courtesy of the artist.

Boston-based artist Heidi Whitman, an American artist of European descent, created an installation titled New World, a work that successfully conveys a sense of unbalance, hundreds of years into the colonization of the Americas. Seen from the doorway of the spare Spencer Finch installation, a large trapezoid built from patches of numerous textiles and other fragments in black, metallic, and warm tones reads like an ancient monument amid an apocalyptic landscape. Ropes of varied textures and tones hang from the ceiling and coil onto the floor, unanchored metaphors of the weight of our inheritance. The mixed media, including found objects such as construction tape and plastic netting studded by metallic matter, contribute to the sense of foreboding chaos.

A close look at historical maps enables us to realize that, despite their utilitarian goals, they are constructs, tangible artifacts of a desire to not only know, but also to control. Indigenous worldviews are often at odds with the aspiration to identify, label, and colonize. A recognition of the divide is visible in multiple artists’ works. What might appear to contemporary eyes like charming errors made in the 1600s wrought incredible pain and genocide to Indigenous peoples who did not have a say in where lines were drawn, or whether to create borders at all.

The exhibition’s premise, and the works on view, can help shift perspectives and develop the critical possibilities of the collection, as its access extended when digitized by the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library. When institutions in Boston and beyond engage artists to collaborate directly with archives, they help stimulate a rhizomatic expansion of how we understand these tangible touchpoints to the past. To paraphrase Fred Wilson, an artist whose “Mining the Museum” exhibition in 1992 created a new paradigm for the potential of institutional critique, people of different backgrounds will naturally look for, and find, different things. Contributions (and better yet collaborations) from diverse points of inquiry will bring us to a spacious and more fascinating understanding of the world.

“Wayfinding” is on view at the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover through February 28, 2021.