On a wet day in February, I met artist Crystalle Lacouture in Wellesley. Bundled in our coats, we strode into the sodden suburban wilds of Wellesley College’s campus, her rescue terrier-mix Moo making sniffing loops ahead and around us. Though a quick walker myself, I struggled to keep up; Lacouture’s long, swift lope is a lot like her paintings and prints: sweeping, seemingly automatic but also thrumming with intention, marked by direct lines and unexpected turns.

We had come to walk the labyrinth. Marked out in handlaid stones, the maze looked old, though it was constructed by the college just a few years ago after its predecessor, formed by split logs, started to decompose. Lacouture watched from the edge as I took a dizzying pass on my own, then joined me, so as we talked we coiled around each other, our eyes trained ahead on the narrow twisting path. Revolving, we discussed rituals ancient and modern, the physical and existential processes of grief and healing, and how Lacouture’s art practice—be it through painting, assemblage, photography, or all of the above—works to consecrate the familiar by asking us to recall what is essential in our lives.

Recalling differs from remembering; rather than focusing one’s attention or behavior on the memory of something past, it is an active engagement—a summoning back, a revival into form, be that ephemeral or concrete. For the last three years, Lacouture’s work has centered on articulating her recollections of her beloved mother, who died of Stage IV lung cancer in 2022, and in opening up avenues for others to commemorate their own loved ones. With her MAMA paintings, Eleven Months (Touching the World) photo series, and Lullaby Archive project, she’s been illustrating the power of maternal relationships and clearing out connective paths much like the one we were walking.

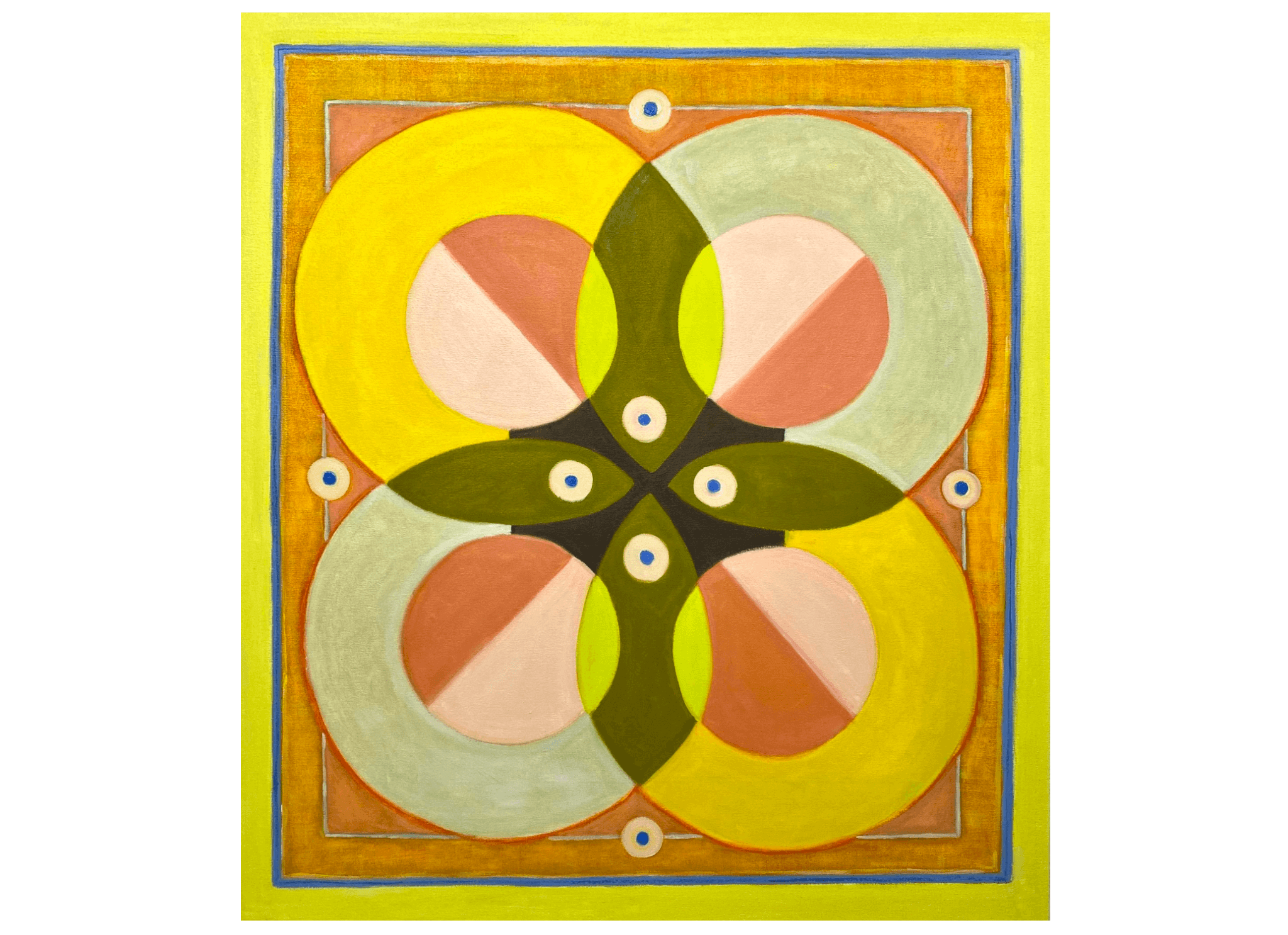

Crystalle Lacouture, Scissors on the Curves, 2023. Oil on canvas. 40″ by 35″. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Later, back at her studio, I studied her 40″ by 35″ oil painting Scissors on the Curves (2023) and was struck by the interplay of fresh tonality and archetypal design. The piece is dominated by interlocking rings mapped out in daffodil yellow and pale mint. Within them, pink and salmon circles, their centers bifurcated with angled lines, draw the eye to the center where Lacouture has arranged four ellipses in a murky mossy green, each sporting an unblinking orb—which can’t help but call to mind the evil eye of antiquity. Their pointy ends and daubed dots suggest the fish of Christian iconography or, if you follow them around the contours of their rings, the snakes and eels of more primeval theologies.

Though the palette is solidly contemporary, with shocks of chartreuse and bands of lemon yellow and cornflower blue, the piece feels rife with secret symbols and accentuates the skilled hand of the maker—Lacouture doesn’t use tape or other masking techniques to preserve her shapes. Standing there, I feel as though I’m looking at a twenty-first-century Book of Kells, a codified vocabulary that—like the illuminated texts from the Middle Ages—promises entry into an intimate and enigmatic world. The kinship with dark-age ciphers is merited: Lacouture studied medieval art history while getting her BFA in painting and printmaking at Skidmore College in New York, and she is drawn to disciplines that privilege rigor and sacrifice.

“Art always felt urgent to me—painting, writing, all of it,” said Lacouture. “I was the first generation from either side of my family to go to college, and I chose Skidmore because I wanted to be at a place where people were serious about many things, people whose drive was inexhaustible and matched my own.”

This sensitivity to the artful in the everyday is something she picked up from her unorthodox upbringing, which saw her shuttled around North America by her French chef father and American mother, a woman skilled in creating warm and welcoming experiences, and who would later go on to become a globally respected herbalist and wellness advocate.

“There was a constant ‘high/low’ style to my childhood that I think informs many of my interests in art and presentation,” she said. “We might have had a terrible, rusty car but our meals were extremely gourmet. Everyone in my family is creative.”

After college, Lacouture spent a decade or so in New York City, working at the Lower East Side Printshop and training with the celebrated installation artist Phoebe Washburn and the legendary Nancy Spero and Leon Golub. These relationships showed her how to channel her passion and drive into a focused and sustained way of living.

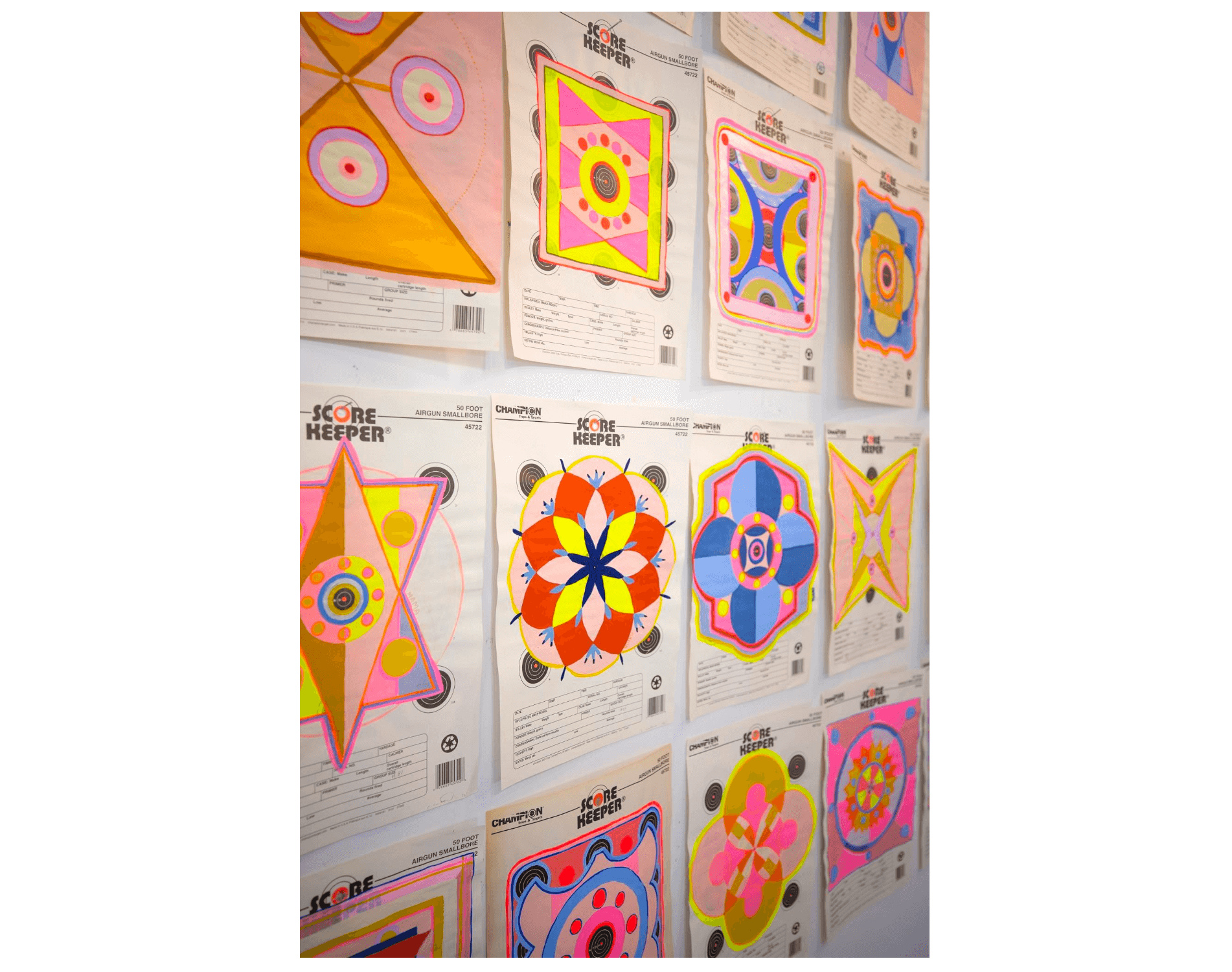

In her studio, a selection of Crystalle Lacouture’s MAMA series hang. Photo by Carlie Febo for Boston Art Review.

“It was a very intimate experience being with Nancy and Leon every day. Sadly, Leon died while I was with them. It was my first experience with the death of a loved one,” said Lacouture. “He would draw pictures in his hospital bed describing how he wanted me to find scissors to cut him free of the tubes and wires and break him out of there. I think it was probably from that point on that I felt like my work had to be about more than just formal things. It had to be about something and do something.”

And so it does. With projects like her Memory Quilts, printed photo collages of her children’s outgrown clothing, or Flags to Fold in the Pocket, large amuletic banners made of hand-printed and dyed shikishi paper, Lacouture captures essential aspects of our collective experience through moments of private inspiration or family bonding. At her studio she flits from in-progress project to in-progress project, piles of wood-block prints and heaps of bells waiting to be strung into tinkling strands of “house jewelry” testifying to her protean method of making. She likes to have multiple pieces going at once, she tells me, as every work informs the others. As they evolve together, they accrue layers of context and meaning, which color, but do not obscure, the pure joy and wonder that lies at the heart of Lacouture’s practice.

“There’s just always been an instinctive need to create, an internal engine that propels the need to work first and then explore ideas and feelings more deeply,” she said. “I think that’s maybe why I’ve always loved outsider art. Howard Finster, Sister Gertrude Morgan, Bill Traylor. The directness of style and the desperate, obsessive need to make even without an ‘art world’ audience. I relate to that.”

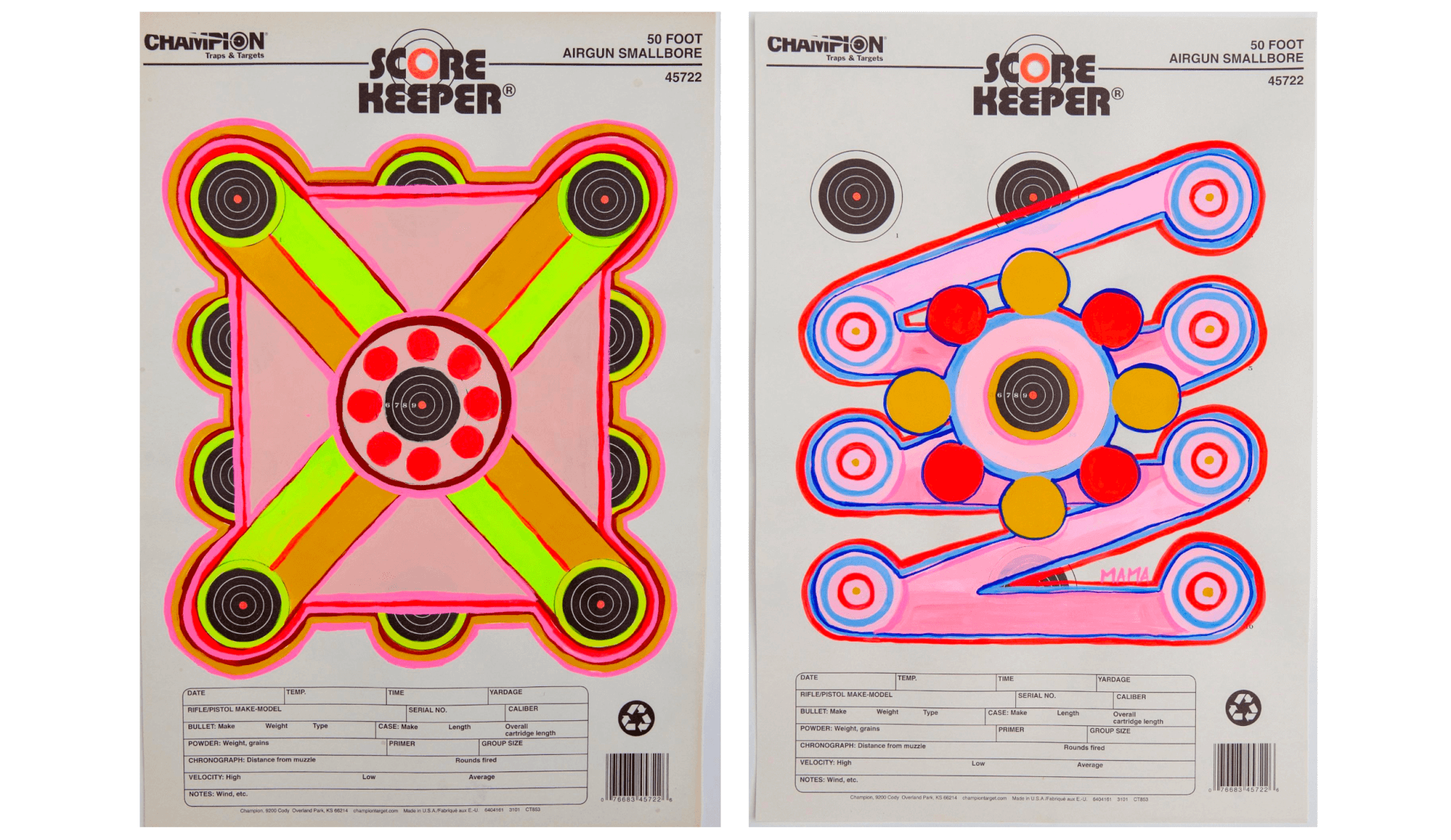

(left) Crystalle Lacouture, MAMA Drawing #56, 2023. Gouache and colored pencil on Score Keeper shooting target. 11″ by 17″. Photo courtesy of the artist. (right) Crystalle Lacouture, MAMA Drawing #61, 2023. Gouache and colored pencil on Score Keeper shooting target. 11″ by 17″. Photo courtesy of the artist.

In October 2020, her practice and its ideal audience narrowed drastically as she contended with her mother’s tragic lung cancer diagnosis. She would survive less than two years, passing in February 2022, enduring the entirety of her treatment during COVID quarantine. To cope, Lacouture concentrated her art practice into a daily vigil, painting bright, glyphic messages to her mother on shooting targets she found at a sporting goods store, imbuing the geometric abstractions with the full force of her adoration, and titling, or signing, or addressing them, in blocked, almost childish capitals: MAMA.

“Practices of repetition and accumulation have always felt devotional to me,” she said. “The act of making small drawings at my desk rather than big paintings on a wall felt radically and physically different. Because the papers are already charged with language and designs that imply violence, speed, and action, and the shapes have intense directionality, I thought I could manipulate that innate power and redirect it towards her healing. A bit far-fetched maybe, but when you’re faced with uncertainty and loss, you’re willing to suspend disbelief.”

Crystalle Lacouture in her Wellesley studio. Photo by Carlie Febo for Boston Art Review.

The commitment, the routine, the evocation—all of this calls to mind the story of one of Lacouture’s favorite artists and influences, Hilma af Klint, whose large abstract paintings claim a sisterhood with her own in terms of vibrant palettes and biomorphic imagery. But where af Klint’s practice required her to act as a receptive conduit for larger outside forces, Lacouture’s demands a conscious distillation of her active attention, anchoring rising pyramids and blooming arcs to the canvas with strong bands of color and pattern, parameters that fasten the pieces starkly to the present. While this duality has been evident in her paintings for years, the daily ritual of the MAMA series has strengthened the immediacy and urgency of the work.

“I do think the MAMA series contributed to a change in my paintings. I started to think about the paintings as objects that related to bodies, or bodies in spaces,” she said. “Working with centrally focused, often symmetrical compositions, I try to create a highly focused station in which to engage with color, shape, and possibly sound—a mutual vibratory relationship.”

A selection of photos from Crystalle Lacouture’s Eleven Months (Touching the World) series hang in her studio. Photo by Carlie Febo for Boston Art Review.

With the Eleven Months (Touching the World) series, she situated that station on the tip of a finger. For the eleven months following her mother’s passing—the traditional length of time set aside for mourning a parent in Judaism—Lacouture kept a heart painted on her left thumb (her mother was left-handed) and took photographs of that same hand touching objects that she wanted to share with her mother. One snapshot finds the marked digit plunged into the pulpy insides of a pomegranate that she’s washing in her kitchen sink; in another, the hand rests on the forehead of her sleeping child. The series has only recently been completed, with the artist planning to collect the resulting 355 images into a book.

“No one had taught me anything about grief,” she said. “It was overwhelming, and this project helped me organize it into little daily parcels. In each of these casual, possibly unremarkable moments there was a real pause in remembering her. The heart was visible to others but private to me, though every two weeks when I went to the nail salon, I had very beautiful and gentle exchanges with the woman manicurist, who would talk to me about my ‘Mama heart.’”

Such exchanges are what, ultimately, compel Lacouture to the studio. As in the medieval iconography she’s so fond of, her practice revolves like an ouroboros, giving and receiving in order to give again. Going forward, she hopes to expand on the connective qualities of her work by generating further opportunities for collaboration with projects like her Lullaby Archive, a crowd-sourced collection of songs that live within, and can be played from, a dedicated website. Late last year, she kicked off the project by mailing hundreds of postcards to friends and colleagues. The front of the card depicted her mother nursing an infant Lacouture, her face angled away from the camera and down to gaze at her child; the back invited anonymous submissions, encouraging folks to submit the songs that were sung to them as children, or those that they themselves sing to their loved ones. For now, the archive is online only, but Lacouture can imagine future lives for the project, possibly recording the songs herself or even transmuting the collection into live performance.

“When my mother passed, there was a moment during the private viewing when my family gathered around the casket, and my sister and I—without discussing it in any way—both stood up and began to sing. The whole room took on a resonance,” she said. “I want to create those moments for others, to help people navigate into the center of a shared experience.”

There are two kinds of labyrinths. The first, made famous by Theseus and his Minotaur, is a multicursal maze; the second, possibly even more ancient and adopted as a symbol of many faiths, is unicursal, with one route in and one route out. These mazes have been laid into the entryways of monasteries and cathedrals since the Middle Ages. Rather than a riddle of false starts and bewildering branches haunted by a monster, they are a single, sinuous path leading you exclusively to the center and, in many traditions, to God. In February, Lacouture and I walked the latter, and I couldn’t help but recognize the kinship between the diagram and Lacouture’s practice: the steady traversing of sacred dimensions, the dedicated, rapt absorption given to the task, and the resolution to find the available blessings in every boundary.

Crystalle Lacouture’s latest solo exhibition, “Evening’s Evening,” is on view at Praise Shadows Art Gallery through November 26, 2023, featuring an entirely new body of work and the debut of the installation House Jewelry. Lacouture’s new limited edition artist book, Eleven Months Touching the World, accompanies the exhibition and is available for purchase at the Praise Shadows Art Shop.