Snaking down Faywood Avenue in East Boston, students from the Manassah E. Bradley School walk alongside Colombian artist Gris One’s vibrant plants, fruits, and birds as they blend with stylized tallgrass, grasshoppers, and other native fauna courtesy of South American artist O. Hanimal. The three-hundred-foot winding mural is not only beautiful, but serves several other functions. Besides being a reminder and reflection of actual lessons studied at the Bradley, it’s also a real-world symbol of how art can facilitate change and empower the next generation.

Over the past few years, community groups like HarborArts in East Boston have ramped up mural production as a way to better reflect the community within the built environment while empowering artists to take ownership and transform their respective corners of Boston. Earlier this month, HarborArts completed their twenty-seventh mural in East Boston. For approximately one-third of those public art projects, the organization teamed up with local schools like the Mario Umana Academy and the Dante Alighieri Montessori School as well as community groups like Eastie Farm—a collaboration launched in 2022 called Harvest.

Matthew Pollock, an East Boston resident, is creative producer at HarborArts and director of the Harvest program. Pollock said the organization’s focus on murals has been more than a decade in the making, with 2013 marking the first time HarborArts installed a large-scale mural in the neighborhood. The last three years, he said, have been explosive, allowing HarborArts to extend their reach into the community, especially through partnerships with organizations like PangeaSeed for Sea Walls in Boston and the growing Shipyard Gallery. Now with the Harvest program, students are learning about ecology and nature in their respective classrooms while also being offered a chance to get real-world experience at Eastie Farms. After digging through the dirt, HarborArts provides the final touch by working with the students to come up with a mural design and tools for painting a wall inspired by their ecological work.

As a part of HarborArts Harvest program this year, artist Felipe Ortiz helps students create a mural to reflect lessons students picked up in conjunction with Eastie Farms and the Dante Alighieri Montessori School in East Boston. Photo by Matt Pollock, HarborArts. Photo courtesy of HarborArts.

After wrapping up the most recent Harvest mural with Boston muralist Felipe Ortiz at the Dante Alighieri Montessori School, elementary teacher Rosie Doucette said her students brightened up when she explained they would be receiving hands-on experience, helping to design and paint the mural.

“It’s something they can look forward to and come visit later on as a fond memory of their place in the world and in our community,” she said. “Each unique bee that the students are contributing to the mural is showcasing the diversity that our community is so proud to cultivate.”

At the Patrick J. Kennedy School, New Bedford-based artist Tom Bob worked with students on a handful of installations, transforming mundane objects like piping and water meters into colorful characters including an elephant, a butterfly, and a monkey.

Ortiz, who has led the mural team for the Harvest program over the past two years, said he’s experienced the impact his projects have had on students. “Collaborative programs like this help raise awareness from different angles, in this case from an educational, environmental, and artistic point of view. At the core, we are helping students gain a wider perspective of what it means to live in a balanced and healthy community,” he said. “Their curiosity and positive reaction is a hopeful sign for a creative community that keeps growing in East Boston. The collaborative aspect of this project fuels students to be involved and take part in a hands-on experience that will be meaningful for years to come.”

In the last few years, Ortiz said he has seen a wider interest in and acceptance of public art in Boston, including the growth and addition of diverse organizations promoting public art. But, he noted, it’s fairly new, and while there are many supporting organizations within the greater Boston area, it still remains somewhat fragmented. “The important thing is to acknowledge that Boston is finally coming around to seeing the benefits of engaging communities through public art,” he said. “We are creating a meaningful dialogue for people to experience and respond in an active urban social environment. These are one of many creative alternatives that are worth funding and I hope it continues to be supported.”

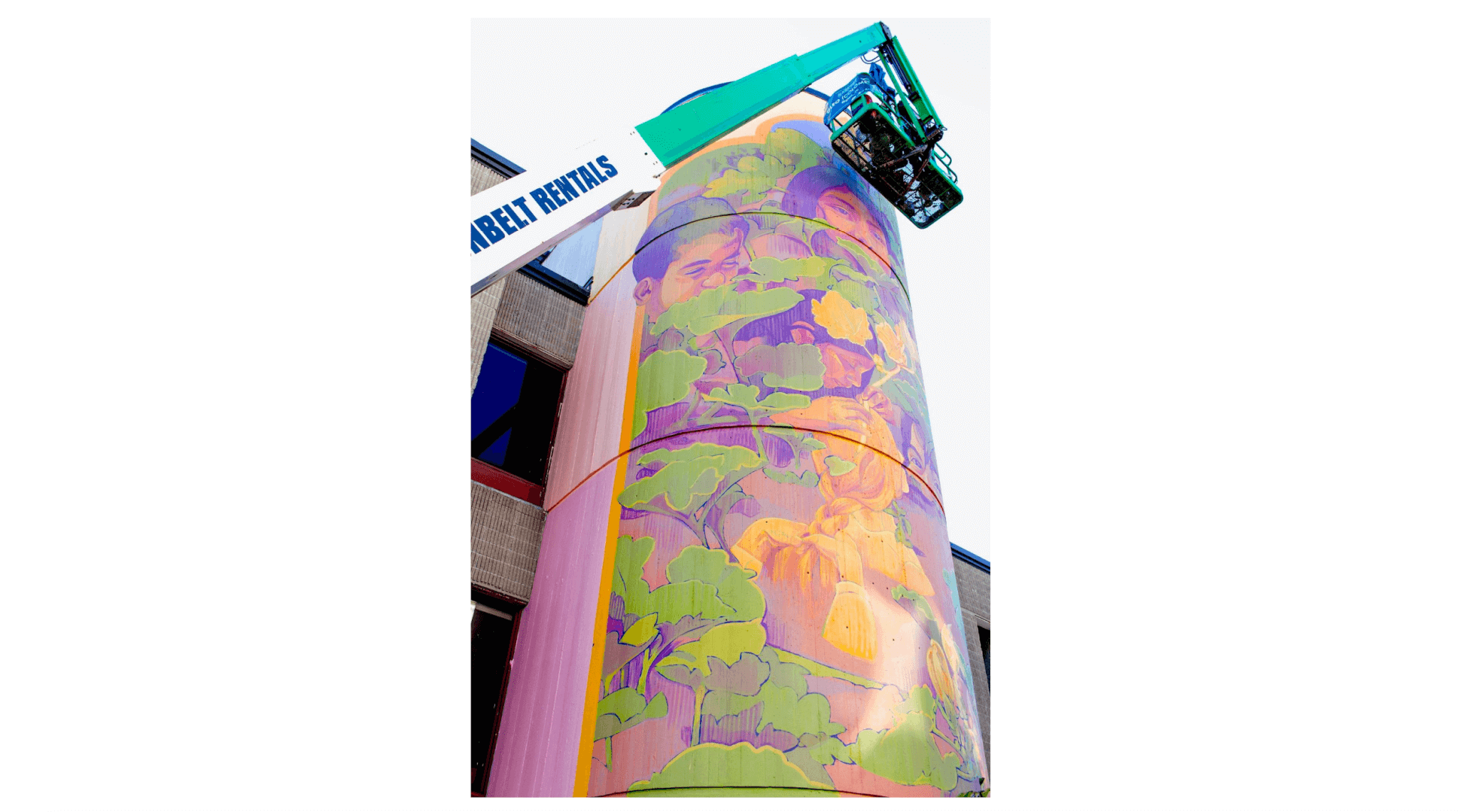

For the first year of Harvest, HarborArts worked with international muralist Gleo (Colombia) at the Mario Umana Academy K-8 in East Boston. Photo by Matt Pollock, HarborArts. Photo courtesy of HarborArts.

After a successful pilot year with murals by Gleo, Yenny Create, and Gris One, Pollock said HarborArts received a proposal video from two young students from the Dante Alighieri Montessori School asking for help. In one of the upper elementary classes, students were given the assignment to create a PSA about any cause that was important to them.

“It was incredible hearing two young community members speak to the valuable impact that street art can have on their environment,” he said. “Before we started painting all of these murals in the neighborhood, it felt like something was missing from the visual landscape that reflected the pride that neighbors have for their community. Eastie has always been a tight community where people from all over the world develop deep connections with each other, but you didn’t necessarily see that manifested in the physical neighborhood itself.”

As Boston’s official mural consultant, Liza Quiñonez has been working with artists, city officials, and community members since 2021, helping oversee the design, planning, and execution of Boston’s public art murals. She and her husband and business partner, Victor Quiñonez, a.k.a. Marka27, have installed dozens of murals across the Northeast with their company Street Theory. In addition to producing works in Grove Hall, Jamaica Plain, Cambridge, and Somerville, Street Theory was a driving force behind the creation and growth of the Underground at Ink Block on the edge of the South End.

In April, the city announced that Street Theory would be in charge of a $3.5 million budget to expand Boston’s network of murals. Thus far, Quiñonez said she’s been tackling mural projects at Malcolm X Park and the Shelburne Community Center in Roxbury while working with the Mayor’s Office of Arts and Culture to plan out new projects and calls for artists. Quiñonez said the new investment is indicative of a rise in acceptance and support for street art over the past decade in many cities, including Boston.

“There has been a shift in perception that recognizes street art as a valuable form of public art and community engagement, rather than mere vandalism. It’s been amazing to see, experience, and now facilitate the increase in city funding for larger projects,” Quiñonez said. “In addition to larger projects, we will also be creating opportunities that meet artists at various stages of their artistic journeys, experience, and skill levels. We want to make sure that we are supporting the next generation of public artists with projects that they can use to build their skillset and grow into bigger projects.”

That includes, she said, the potential of expanding the mural program into and around Boston Public Schools. Quiñonez said she knows that murals can encourage creativity, foster a sense of community, and be representative of the students and their surrounding communities. In addition to East Boston, she pointed to Madison Park High School, which features some of the best street art in the city courtesy of Geo “GoFive” Ortega and Rob “ProBlak” Gibbs, who have painted and curated the work there. “The Lab,” as it’s called, was developed by former students and now features work from local and international artists.

Ortega grew up in Boston and said it’s only now catching up to so many other cities that have allowed artists to embrace street art. Now a teacher at the long-running nonprofit Artists for Humanity, Ortega has integrated his love for teaching with the creation of public art. He recently finished a mural at the Eliot School in Boston.

“I do at least one mural with my junior class at Madison Park as a final test every year, in addition to working with other organizations around the city to create public art with students,” he said. “The students take pride in leaving a mark on their school. One of the most important things they walk away with is teamwork. Learning to build and critique in order to create an amazing piece is an important tool to have.”

Ortega said some of his first art teachers in Boston were graffiti writers, so he’s happy things are moving full circle. “I would walk from Roslindale to Roxbury looking for new work from the [African Latino Alliance] crew and the IW crew,” he said. “There are so many people who have been working in Boston: TakeOne, Soems, ProBlak, Odesy, kwest, Brand, Imagine, Silvia Lopez Chavez, Rixzy, Deme5, Marka27, and so many more. I’m excited because I’m a part of it. We are literally making history, creating an outside gallery all over the city.”

Felipe Ortiz’s colorful mural at the Dante Alighieri Montessori School in East Boston was completed with the help of students and reflects some of the lessons learned over the course of the year. Photo by Zach Heyman, HarborArts. Photo courtesy of HarborArts.

School mural projects, especially, Quiñonez said, have a profound impact on communities. They can foster a sense of pride and ownership among students, teachers, and local residents while showcasing the potential of art as a means of self-expression and communication. And then there’s the educational aspect.

“For example, our mural Sangre Indigena by visiting artist Don Rimx highlights a moment of awareness for students and the surrounding community to acknowledge Indigenous communities and the endemic of murdered and missing Indigenous women and children,” she said. “The power of public art, especially murals, lies not only in their visual impact but also in the process of creating them. They serve as catalysts for conversations, collaborations, and connections within communities. As public art becomes more recognized and supported, it will continue to contribute to the cultural vibrancy and identity of cities like Boston and beyond, and I’m thrilled to play a small role with diverse artists to create more work across the neighborhoods.”

That kind of work, Pollock points out, is time consuming and requires a healthy amount of funding. From fundraising, securing walls, and coordinating installation logistics to facilitating community engagement, procuring materials and equipment, and managing site operations, preparation, installation, cleanup, and documentation—the list goes on.

“The biggest challenge—at least in this city—is securing walls,” he said. “Getting the permission of a property owner or stakeholder to paint a mural is tough in Boston, even when you have a legacy of world-class, professionally installed murals to point to. Because street art has only recently become part of the mainstream here in Boston, it’s uncharted territory for most property owners, and it’s understandable that they’re scared of unknown risk. All we can do to change this as creative producers is to keep making murals, create familiarity with street art, and eventually—hopefully—a greater demand for it.”