In Nubian Square, a man and woman, wearing masks and black T-shirts, hold hands. The man rests his arm around the woman’s shoulder, his loose fingers grasping a cardboard sign with the words “disarm, defund, disband.” The couple, as they appear in the right foreground of Lauren Miller’s photograph, gazes pensively beyond the shot’s left frame; their ebony faces glow in the June heat. An all-white crowd, also masked and looking in the same direction, is gathered around them. Since the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Tony McDade, and other Black people in incidents of police brutality and racist vigilante violence, Black photographers like Miller have documented Black Lives Matter (BLM) demonstrations as visual testimonies for future generations. Taken at the risk of arrest and physical and verbal assault by police and counter-protesters, often for minimal financial gains, images of Black bodies protesting have always been contested ground for representation and meaning. With the reentry of the Black Lives Matter movement into mainstream American consciousness this summer, mixed narratives around the movement’s agenda and validity have been constructed from shots and videos of a blazing police station and fists raised in silence. One theme that complicates these stories are images of Black joy.

Given that these marches and rallies are perceived as sites of mourning and anger, practicing Black joy might seem absurd. However, as writer Chante Joseph notes in her exemplary essay for British Vogue, “To resist the omnipresent, intrusive, and pervasive nature of white supremacy, we must also allow ourselves to be rebelliously joyous.” Capturing acts of celebration—even, or especially, at protests—reveals an alternative form of dissent that troubles the incendiary way BLM protests are frequently represented. Lauren Miller, Thaddeus Miles, Philip Keith, and Sam Williams are four of many Black photographers who covered BLM protests in Boston this summer. Each of them centers Black joy in their photographs. Beyond documenting this crucial period in history, their work asks us to embrace the idea that there is room for celebration alongside urgent confrontations with power. It also helps us conceive of photography as a vehicle for individual and communal healing, particularly for Black bodies that bear the brand of centuries of systemic racism and dehumanization.

Hundreds of people gather in Nubian Square to participate in a march organized by For the People (F.T.P.) to defund the police and fund communities on June 10, 2020. Photo by Lauren Miller.

Photography As Activism

Influential Black photographer, writer, film-maker, and composer Gordon Parks said in a 1999 interview that a camera could be “a weapon against poverty, against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs.” This idea, as relevant and forceful now as then, has implications for how we should approach image-making. Photography has a long history of intentionally— and unintentionally—doing activism. Its “recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event,” as street photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson famously put it, has helped ignite social movements and undermine oppressive governments and policies around the world.

The rise of the smartphone over the last twenty years means there are more possibilities of using photography for activism than ever. Keith wonders, however, if producing and circulating photos is still as useful for mobilizing support and effecting social change today as it was in the past. “Images of the Vietnam War changed the mind of the country. People didn’t know the atrocities that were happening; once they saw them they were like, no, we don’t want to be a part of this,” he says. “Whereas now people have seen hundreds of thousands of images of this struggle right from their phones. Yet there have been no new policy changes, and the country is just as divided as when we started.”

Keith notes that the images still hold value as historical records but is skeptical of how effective photography can be as a means for activism. In today’s hyper-digitized, truth- subjective environment, our easy access to photos muddles its role in protests. This raises the question: is photography only suitable for marking attendance, or can it incite revolution? As Keith asks, “What images need to be made for people to say, ‘This is happening in my city. I need to stand against this brutality’?”

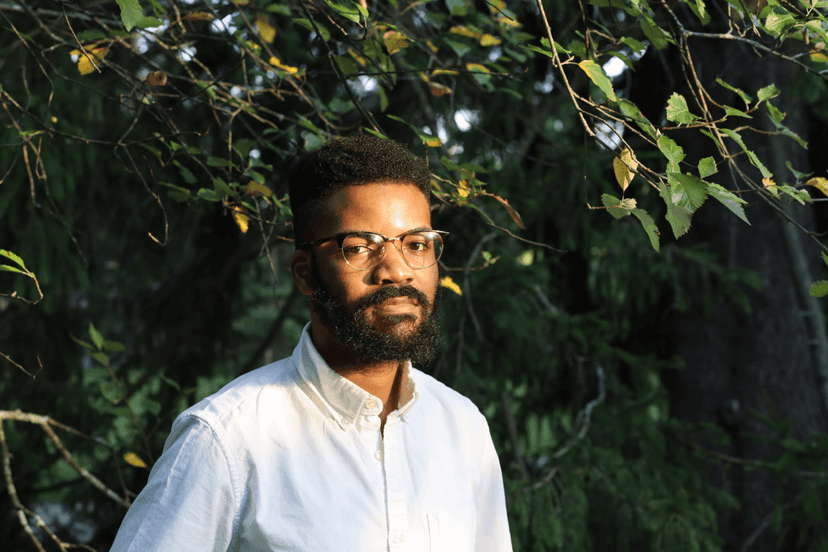

Portrait of Graz De Oliveira at the Trans Vigil at Franklin Park, June 13, 2020. Photo by Philip Keith.

Artist Kalamu Kieta painting the Black Lives Matter mural onto Washington Street between Eustis Street and Palmer Street in Nubian Square on July 5, 2020. Photo by Lauren Miller.

Photographing Black Joy and Healing in Spaces of Dissent

American culture has often failed to respect and accurately represent the emotions of Black people. Historically, our bodies expressing anger, sadness, and joy have been thought of as dangerous and in need of control, or used to reinforce stereotypes and notions of Black racial inferiority. Film, literature, music, and photography have all participated in this practice. In the context of protests that center the lived realities of historically marginalized peoples, telling an authentic story through images requires a connection with the issues being raised and sentiments that ground these spaces of dissent. When BLM and other demonstrations led by Black people are only documented with images of violence or grief, the range of other emotions and moments that these protests contain, such as celebration, are missed. When local artists painted a Black Lives Matter mural on a street in Nubian Square, for instance, Miller rushed to document the scene. “It felt so Roxbury to me,” she said. “They were able to make a mark on something happening nationally.” In that moment, Miller captured an alternative perspective of the nature of BLM protests, one that communicates a sense of defiance and joy through art. This moving message would likely have been lost if the demonstration was captured according to the narrow lens much of the mainstream media has framed it in.

Williams believes that this joy can look like Black people “living fully and unapologetically; not wavering to roles and boxes society will try and put them in.” Miles, on the other hand, takes a more personal angle when he emphasizes that this joy is “having the opportunity to be authentically Black in who I am.” These definitions articulate how Black joy is a radical statement of physical and emotional survival.

Sometimes this statement can be loud and collective, like when protesters chant verses from Kendrick Lamar’s 2015 rap anthem “Alright” or crowds break out into the Electric Slide and Cupid Shuffle at a Dance For George event in Harlem. Other times, it is more intimate, like couple Kerry-Anne and Michael Gordon having the “first look” on their wedding day in the middle of a BLM demonstration in Philadelphia. When the presence of anti-Blackness seems over-whelming, acts of celebration provide our bodies and souls with the nourishment necessary to fuel the struggle for freedom and transformation of our public institutions.

Black joy can be a potent force of resistance and resilience. And yet, how can we sustain our delight in ourselves when the crowds dissipate and we return to a society that doesn’t love who we are? As Black communities throughout the country endure the ongoing trauma of slavery and what author Isabel Wilkerson terms the “American caste system” of race, the long-term task of healing is vital. Perhaps the most important way to start is redefining how we see ourselves.

Attendee at the “Sage the City” event in Nubian Square on August 8, 2020. Photo by Thaddeus Miles.

“Dee” holds her fist up before speaking on the Commons about Blue Crime Blue Dime at the Unity March from Nubian Square to Boston Commons, July 26, 2020. Photo by Sam Williams.

Historically, “a lot of the people who were able to own a camera were not Black—were not people of color—so I think the more people of color we have out there taking photos the better,” says Williams. “When they show their perspective, we are able to learn from them.” Keith applies this very idea to his work, saying he aspires to put “images of Black people out into the world with the normalcy and prevalence we’ve been giving to white people” and help spur “structural change that shifts the narrative little by little over time.” Following in the footsteps of portraiture taken by Black photographers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, photography can develop and popularize new depictions of Black people that communicate their inherent dignity and worth.

Faith and spirituality can also play a key role in healing. Over the summer, there were several local religious gatherings to lament and condemn lives lost to police violence, anti-Black racism, and white supremacy, such as an interfaith memorial service for Floyd, Taylor, and Arbery in Jamaica Plain and a Black Jewish-led BLM vigil in Brookline. While some offered prayers, others offered smoke. At an event called Sage the City, Miles captured photos of herbalists and healers dressed in white engaging in smudging, a practice of burning sage or other herbs to clear negative and harmful energies while offering protection and harmony. Images of this ceremony, like the memorial service and vigil, offer a way to pause and reflect on religious and spiritual practices that have kept generations of Black people hopeful and resilient. It also helps us understand that true healing doesn’t end with self-appreciation and respect; it involves the transformation of the soul, too.

But Miller believes that finding and creating images that bring healing to the Black community require establishing relationships and connections with it first. “It’s really important for photographers of color to feel personally entwined with the community or movement,” she says. “It’s the most authentic way that movements, and protests, and communities can be documented.” Her words speak to the importance of Black photographers capturing the lives of Black people. While Black people and culture are not monolithic, Black photographers can give an honest, intimate, and thoughtful representation of the people and the places they come from.

The Sistahs of the Calabash, an Afro-Indigenous collective for ancestral reverence and community healing, lead a group in the “March to the Statehouse” protest on June 22, 2020. Photo by Thaddeus Miles.

In Episode 3 of A Beautiful Resistance, an essay and film series by Boston Globe culture columnist Jeneé Osterheldt, she incisively comments on how a predominantly white gaze determines how stories are told. “The gatekeepers have always been white. When you tell Black and brown stories through that lens, through the white lens, an erosion happens,” she says. “To have [Black] photographers on the ground capturing those pictures, they look different. They feel different… It’s hard not to be stirred in your soul.” Photography will play a critical role in how we understand and view marches, rallies, and uprisings of the summer of 2020—now commonly known as a “racial reckoning.” However, with whites composing 70.9% of the American photography industry (as of 2018 according to Data USA), questions remain: how will the story of movements like Black Lives Matter be told? What is lost when protests by and for people of color are shot only by white people and, as Thaddeus Miles notes, “the Black voice of photography is ignored”?

Osterheldt states that what isn’t told enough about Black-led demonstrations is “how much love is on the ground.” Miller, Miles, Keith, and Williams are part of a wave of Black photographers who are striving to reveal this love through images of Black joy and healing. Their work not only adjusts how we think about Black people in protest, but also helps ensure that we are known by more than just our rage, rightful as it may be. Their photos further demand, as Williams mentioned, that Black people be seen as fully present, whole in our bodies and possessing a multi-layered humanity, with the hope that viewers will be motivated to fight for and defend it both on and off the streets.

This story was originally published in Issue 06: Timestamp in January 2021. Additional photography is published in the print version.