For her first solo museum presentation in the United States, now on view in Boston at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Tammy Nguyen has made two panoramic paintings and four large-scale portraits with corresponding artist books, each themed around a protagonist or event that is central to American and Vietnamese cultural identities. This exhibition weaves together nineteenth-century American ideologies of ownership and nature with land reform programs in Vietnam during and after the war. Nguyen is interested in moral ambiguity, visualizing the way colonization sows the seeds of different belief systems while eradicating histories and hybridizing cultures. Her work assembles the big storylines and buried ephemera of the past to bring to light the complexity of our present.

I first learned of Tammy from my partner, a historian at The Cooper Union, who was delighted that he had found an art student equally interested in history. I heard about her Fulbright Fellowship to Vietnam, and later, when Tammy was at Yale and I was her critic, I saw how her research into family history played out in epic mythological paintings and exquisite artist books. In the years since, I’ve watched her continue to comb through the tangles of the past and make sense of it through her rich, multidisciplinary practice of collage, painting, printmaking, and writing.

The following conversation has been edited and condensed.

Josephine Halvorson: I’m standing in your studio in Connecticut and looking around at all the work you’ve made for your upcoming ICA Boston show. There’s a lot going on in terms of subjects, colors, and materials. The paintings seem to be almost vibrating or flickering—alive like the late August natural world that surrounds us in this barn. Even up close your paintings have a real density of visual information. Tell me what I’m looking at and guide me through the material timeline of your paintings.

Tammy Nguyen: So what you’re looking at is a panel with paper wrapped around it. When I was looking for a painting surface, I wanted to find something that was intrinsically a color, so for a long time, I was playing around with different grounds, as you probably remember when I was in grad school. With these paintings, I laminate the whole panel, like a book cover, so it’s super, super flat. The cool thing about paper is that it takes water media so well. As you add water, the paper continues to stretch, because paper wants to become flat, resulting in a really nice drum-tight surface.

JH: How do you apply color to the paper surface? I see calligraphic brush strokes but also washy pours and shimmery stamps.

TN: I paint with watercolors, Flashe, ink, and pastel. And then there’s gilding. I often use this silver, which oxidizes at different degrees, turning red or blue or black. Some of the gilding happens after the midway point of the painting. I use an acrylic size, which is very sensitive when it dries to a tack and allows me to gild intricate brush marks. One of the last things I do is the hot stamping. Remember when I took the class at North Bennet Street School? That’s where I learned how to gild on leather, which informed how I hot stamp my paintings. For the ICA, Boston show, I got these brass tools made in England, and they are all based on propaganda materials that I found in the research for this show. I use stamps like pieces of language which take on different meanings. When you look closely, you’ll see that these are in the shape of a Vietnamese official attending to votes. But at a distance it can look like a planet or a twinkle in the peak of a mountain.

JH: There’s another association of stamping in here—a bureaucratic one—as if you are officiating the record of your own work.

TN: Some stamps are taken directly from the research documents related to the land reformation papers. The stamps note things like “document received” or “urgent” or “approved by the Department of Agriculture.” I like using these stamps because they appear as texture from afar, but when you get up close you realize it has semantic value, symbolic meaning, and a historical context.

JH: The stamps don’t change size from one painting to the next; however, the scale of each painting does. The stamps chart change and evolution, registering them to each other. They’re like icons in the legends of maps.

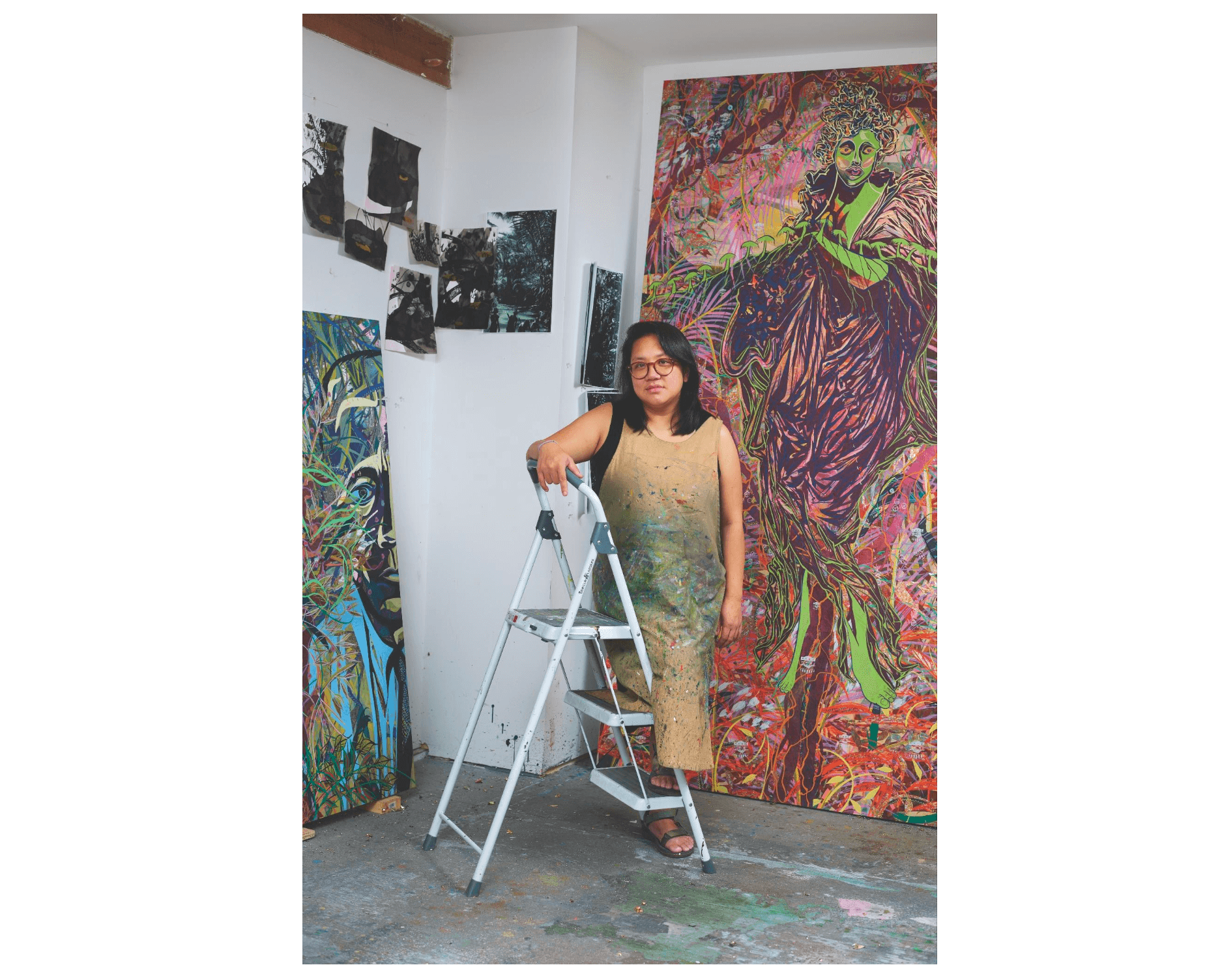

Inside the artist’s studio just days before the paintings made their way to ICA, Boston. Photo by Izzy Leung for Boston Art Review.

TN: Yes, scale is so important in these works! I like the globe stamp so much. It’s a circle that is an eye, that is a planet, that is a berry, that is also a button. I love the slippage between something so modest and yet so mighty.

JH: This slippage also happens through your use of camouflage.

TN: I’m really happy that you brought that up. I think camouflage is great because it relates to how I think about shape and color, the ways that these formal elements oscillate between being seen and unseen. I’m not much of a blender. Rather, I’m always trying to combine a line with a shape or two shapes adjacent or overlapping.

JH: I’m curious if there is an underlying philosophy in these shifting and simultaneous scales and camouflaged motifs. In your work there are always opportunities to discover multiple meanings at once—the way a military helicopter becomes a mosquito, or the way a leaf becomes a face, for instance—but these tricks of the eye serve bigger themes in your work, no?

TN: Yeah, it’s like a big octopus of meaning. If there is an underlying philosophy, then it’s one of confusion. I’m so interested in ambiguity and moral ambiguity. For example, in the fourteen works I showed in the Berlin Biennale—each a station of the cross being consumed by the tropical environment of the Indonesian island Pulau Galang—I think those really exemplify what I mean by moral ambiguity, where faith and salvation are brought to a community through conquest and erasure. That’s so crazy, right? It would be wrong to deny the sense of hope and salvation that Catholicism has given to people because it has brought communities together, despite the violent histories that follow in the wake of organized religion. Colonialism and conquest have similarities. In this recent work I’ve been thinking a lot about land reformation and its connection to liberty: how owning land frees an individual within the framework of capitalism, how this process erases and displaces and also creates and shapes culture.

JH: You’ve spoken about the concept of “confusion,” which is such a material word to me. It suggests the mixing and mingling of things, even those which fuse together to become one.

TN: Things really do derive from disparate places, times, and histories. For instance, for the ICA show, I made Shot Heard ’Round the World, a fusion of the First Battle of Lexington and Concord with East Asian landscape painting and the propaganda cartoon that I found in the land reformation papers. And this is the Minute Man [statue] that’s in Concord. The painting stitches together all these things, but aims to do so in a way where the world is one: not just through composition but through materiality.

JH: That density of disparateness, the constant collage of imagery and points of view, is what makes your work so contemporary.

TN: I think that these paintings are very of our moment—right now—because we live amidst so much information. This painting can only be made now because of the access I have to these types of historical and visual information.

JH: Tell me about some of the archival information you’re using and the research you undertook for this body of work, which appears in both the paintings and the correlative books.

Tammy Nguyen, Ralph Waldo Emerson, 2023. Watercolor, vinyl paint, ink, screen printing ink, pastel, and metal leaf on paper stretched over panel, 100″ x 60″ (254 x 152.4 cm). Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London. Photo by Mel Taing. 2023 © Tammy Nguyen.

TN: So the show at the ICA was initially inspired by Tyler Green’s book Emerson’s Nature and the Artists. [Curator] Jeff [De Blois] and I talked about it a lot— he was a great person to banter with and gave me the freedom and time to follow the ideas that emerged through what I was reading. It’s amazing how Green draws a clear analogy between what is happening in the United States in the nineteenth century and how the Transcendentalist movement envisioned America, and how that is reflected in contemporaneous American landscape paintings. I started to think about Manifest Destiny as being present in American soft power. And then I started to think about the USAID and other projects led by the Department of State related to the land reformation efforts in South Vietnam.

During my initial research I found out about a collection of papers in the National Archives and Records Administration located in Maryland. They were the files of J. P. Gittinger, who was the assistant agrarian reform specialist between 1951 and 1957. These papers were all related to the US land reformation projects in South Vietnam during the war. There were many different kinds of papers, and one thing I really liked were the budget sheets that listed all of the expenses, such as machinery and personnel that in theory would organize the land, which, in Vietnam, is a tropical wilderness. Aside from the accounting, there were also propaganda, cartoons, handwritten notes, and folk songs, some of which I had translated and used in the artist books included in the show. The songs are beautiful and are intended to convince folks of this new way of thinking about making a living in this new economic system.

I used some of the papers in the paintings, like here in Three Vietnamese Officials Study Land Reform, which tells the story of Vietnamese officials who are sent to Thailand and Japan to study land reclamation. There’s a budget sheet which is used in the background. Over there is Ngô Dình Diêm, a portrait of the first elected president of South Vietnam, who really welcomed the United States and was later assassinated. The man lurking is actually the US ambassador at the time, who later became a senator from Massachusetts, which is a great coincidence. I sourced the image from a cover of a magazine.

Tammy Nguyen, Ngô Đình Diêm, 2023. Watercolor, vinyl paint, ink, screen printing ink, pastel, and metal leaf on paper stretched over panel. 100″ x 60″ (254 x 152.4cm). Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London. Photo by Dan Bradica. 2023 © Tammy Nguyen

JH: So you’re bringing together the history of modern Vietnam—stories and documentation about the ways land was reclaimed and reformed after the war—with American ideas of ownership and liberty, concepts which have their roots in nineteenth-century Transcendentalism?

TN: Yes. I think that the juxtaposition is valuable because it brings to light these different connections, if that’s the right word, between the two countries. Personally, it’s also exciting for me to explore these issues of moral ambiguity and confusion because I’m interested in thinking about how my own mind was formed. Like how did I come to have the values that I have, right? Why do I think about individualism in the way that I think about individualism as a Vietnamese American woman? I’m interested in drawing these connections, because I’m trying to find some kind of meaning that elucidates my own mind’s formation.

JH: As artists, we are often drawn to the histories and mythologies that create the conditions for those of our elders. It’s as if we understand the lineage from those we’ve known personally, but what about those who came before, those just slipped out of reach?

TN: Well, we’re all trying to figure out that same question we might have asked in high school; “Who am I? Where do I come from?”

JH: OK, I understand this cultural hybridization you’re describing and visualizing of both Vietnamese and American cultural inheritances. But there’s one painting in this group that I can’t place—the only portrait of a woman. Who is that?

TN: That’s Demeter! When I was conceiving of this show, I didn’t know that I would include her, but she seems to fit in because the whole show is about farming and land and growth. She’s also pagan and therefore part of the Western canon that was displaced by Christianity. Something that’s important in my work right now is including different markers of faith that were later eradicated. I’m interested in the making of ideologies and what it takes for one dogma to replace another.

JH: Emerson writes in his 1837 essay Nature that “[no one] owns the landscape. There is a property in the horizon which no man has but he whose eye can integrate all the parts, that is, the poet.” We know from W. J. T. Mitchell and Angela Miller that the act of seeing or surveying the land, as in the Hudson River School painters, can be its own form of colonization. What is it like for you to depict nature?

Installation view, “Tammy Nguyen,” on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston from August 24, 2023, to January 28, 2024. Photo by Mel Taing.

TN: Let’s take the example of this maple leaf. To paint it, I just look out my window. I’m always trying to find ways to make a shorthand from observation. I didn’t draw that directly; instead, I’m looking at the veins and the whole body of the leaf. I see that it has five points that come out. Look up at the tree— the leaves overlapping on top of each other look like a bunch of zigzags, then the veiny bit starts to appear. And then the way that the shadows kind of come down is another kind of triangle. I would take all of these observations and interpret them as marks. And so it’s not observational in the way one would draw from life, but it is still observational, more like a script. Handwriting and calligraphy is so important in my work. It’s like “How do you make an image just come out of your arm?” like it’s second nature, like writing.

JH: We’ve spoken about the ways that your own hand mixes and mingles with materials, techniques, histories, and archives. But what about other forms ofcollaboration? Since 2016 you’ve run Passenger Pigeon Press and published Martha’s Quarterly. Tell me about these interdisciplinary projects that coexist alongside your painting practice.

TN: As I reflect on my collaborative projects, I realize how the spirit of interdisciplinarity that I gained in my education has helped me evolve my practice. Cooper Union instilled the discipline in disciplinarity, making us so invested in medium and form. Then at Yale, you come in with said discipline and work to unpack it and make connections across the university. When I was at grad school, I started learning about taxidermy, which helped me break out of abstraction. As an undergrad, I kept making the same marks over and over again. And I think something that was really valuable about Yale was just being able to crack open mark making by engaging with scientists and anthropologists. And so, as I reflect on Martha’s Quarterly, I realize how it has helped me continue to evolve the practice. I’m constantly learning from other people.

Tammy Nguyen, Summer (detail), 2023. Bookcloth, book board, vinyl stickers, cardstock, woodblock printing, laser cutting, inkjet printing, photocopy, polymer letterpress, rubber stamping, hot stamping, and collage on various papers. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London. Photo by Mel Taing. 2023 © Tammy Nguyen.

JH: You’re one of the busiest and most focused artists I have ever met. You also teach at Wesleyan and have just had your second child only a couple days ago! I suspect once this work heads to the ICA you’ll begin working on your next body of work. Tell me about what you’re envisioning.

TN: So, I mentioned earlier that I’m really interested in what makes an ideology or faith. Right now, one of my big projects is a three-part show inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy, where each show references a book in the series and draws an analogy with some kind of geopolitical theater. Each show takes over one Lehmann Maupin gallery over the course of three years. Last spring I finished the Inferno show, which took place in Seoul. There I compared Virgil and Dante’s descent into hell to the space race during the Cold War. And now, I’m just beginning Purgatory. It’s an awesome book because it’s so imaginative! I’m honestly really surprised that it hasn’t gotten more attention. I’m thinking of purgatory as a kind of spa for your morals because you’re cleansing yourself to go to heaven, and the cleansing happens through poetry or prayer. Dante depicts purgatory itself as a mountain with seven crescents on it, each representing different sins. And there’s other cool shit there, like plants that keep growing up the mountain. I think the analogy I’m going to make is something about mining, where purgatory is a mountain that you climb … but I want to go inside.

Tammy Nguyen at work in her studio. Photo by Izzy Leung for Boston Art Review.

“Tammy Nguyen” is on view at Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston through January 28, 2024.

This piece was originally published in Issue 11: EMERGE, our fall/winter 2023 issue. Order it here.