Before it was the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, MassArt was a normal school, the nineteenth-century equivalent of a teachers’ college. The delightfully named Massachusetts Normal Art School was founded in 1873 to train drawing teachers for the Boston Public Schools.

So normality is a fitting theme for a show celebrating the college’s 150th anniversary. “The Myth of Normal: A Celebration of Authentic Expression,” at the MassArt Art Museum (MAAM), takes its name from the 2022 book The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture by Dr. Gabor Maté and Daniel Maté. The show, like the book, explores the dark side of normality—the dangers of abandoning our true selves in order to fit social norms. In the words of Mari Spirito, the show’s curator, “Trying to conform to society makes us ill—not just emotionally and spiritually, but physically.”

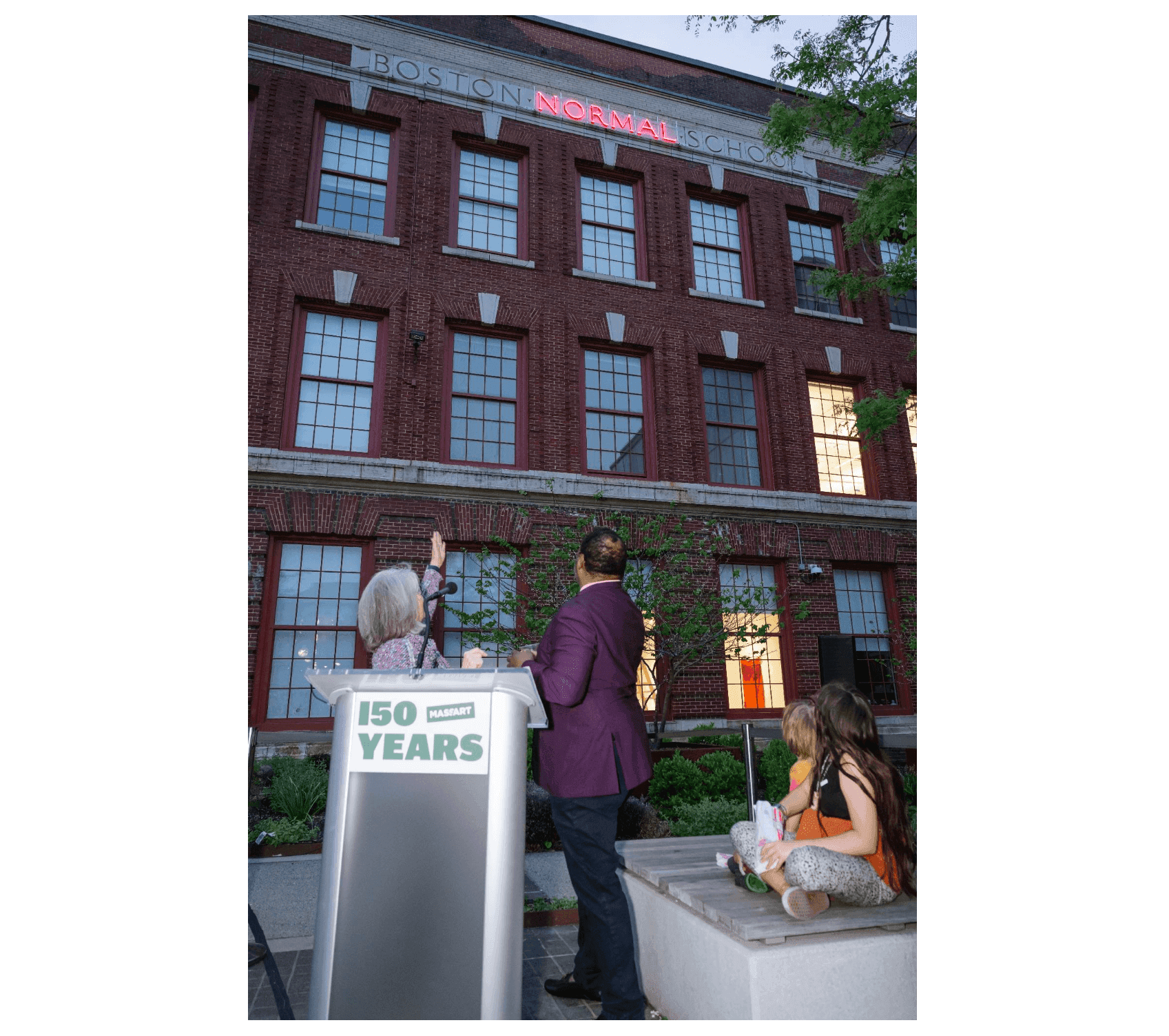

Of course, “normal” isn’t all bad. The first piece you encounter in the exhibition—if you look up—explores the word’s many connotations. MAAM is located on the former premises of a different teachers’ college; the words “Boston Normal School” are still inscribed on the lintel of the building. In a site-specific installation commissioned for the show, artist Steve Locke has retraced the word “Normal” with pink neon letters. The piece emphasizes the importance of individuality and resisting conformity, but it’s also celebrating the school’s history and impact. MassArt is the first and the only publicly funded independent art school in the US; part of its mission is to make art and art education accessible.

This more positive understanding of normality—normality meaning accessibility, ordinariness, belonging to everyone—also appears throughout the show. Many of the artists featured in the exhibition, all of whom are MassArt alumni, use inexpensive, everyday materials and found objects in their work. Art, the show suggests, can be made of anything and should be available to everybody.

MAAM has two exhibition spaces, one upstairs and one downstairs. From the foyer, you enter the downstairs gallery through a glass door, behind which stands an installation by Heather Rowe. The piece, which consists of a video and a series of rickety doorframe-like structures, is inspired by a 1974 incident in which a woman reported being assaulted by a phantom. When parapsychology researchers tried to film the phantom, they captured only arcs of moving light. It’s an eerie, literally paranormal piece, but the metaphor—of being violated by unseen forces— is, for many, a familiar one.

The other pieces in the gallery’s first room also relate, somewhat tenuously, to the theme of “the body as architecture.” On the wall opposite Rowe’s piece are two large-scale photographs by Zhidong Zhang. In one image, the artist is shown in his backyard wearing only underwear and red high-heeled shoes. He’s standing in front of a fence and hiding, futilely, behind a tree branch; through the leaves, his gaze meets the viewer’s. The power of this image comes, in part, from its almost-ordinariness: Zhang subverts our expectations and, in doing so, forces us to wrestle with our own social conditioning.

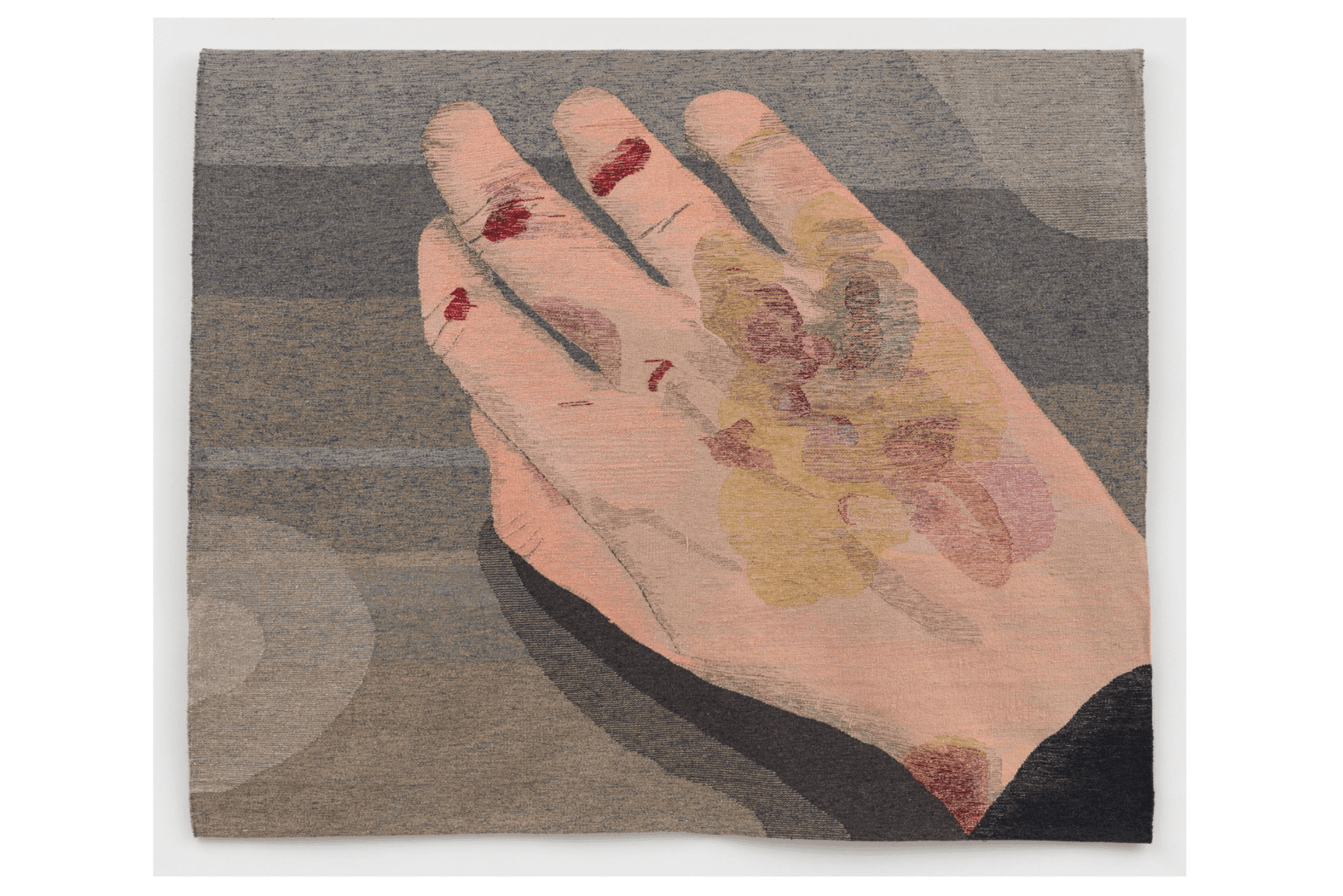

Around the corner, a new theme emerges: “unheard and untold stories” explores the effects of systemic social oppression more explicitly. On the far end of the space hangs a tapestry by Erin M. Riley showing a bruised and cut hand. Nearby hangs a clock stopped at the exact time of the Hiroshima bombing; around the edge of the clock, artist Mimi Smith has painted the words “time heals nothing.” Along the gallery’s longest wall hang a series of televisions showing videos by various artists, which viewers can watch from the comfort of the diner booths placed in front of each screen. In one, Kittens Grow Up (2007), experimental filmmaker Luther Price intercuts found footage of cuddling kittens with footage of a working-class family experiencing various crises: alcoholism, financial stress, neglect. The contrast is meant to shake the viewer out of complacency, to remind us that the struggles of the family on screen, however prevalent in our culture, are in fact profoundly unnatural, abnormal.

Truth-telling is a brutal business: there’s power in these images and narratives, but not much joy. So after walking through these rooms, the upstairs gallery feels like a relief. Here, at last, we find not just critiques of society but something like healing. One particularly eye-catching piece is a floor-to-ceiling mural by Ukrainian American painter Maya Hayuk. The colorful mural, which was painted with house-paint rollers, is based on geometric embroidery patterns Hayuk learned from her grandmother; it also incorporates Ukraine’s coat of arms (a trident). In the corner, in Ukrainian, are the scrawled words “Glory to Ukraine.”

The pieces in this upstairs room are more abstract than those downstairs (though there are still plenty of representational works, including two striking paintings by Stephen Hamilton that show scenes from Yoruba mythology and a joyful self-portrait by Boston School artist Tabboo!). There’s a mirrored cube by minimalist sculptor Jackie Winsor and two glass orbs by glass artist Nancy Callan. It’s as if breaking free from society’s imposed structures also allows one to break free of the representational, physical realm; and, indeed, there’s a spiritual undertone to many of the works.

The most memorable pieces in the room, and in the show, are a series of sculptures called Spirits of Manhattan (1993–1996) by Kathleen White, a Boston School artist who died in 2014. During the height of the AIDS epidemic in Manhattan, White began to collect wigs from drag performers who had died, some of whom were her friends, some of whom were strangers whose possessions had been left out on the street. From these wigs, and from hair donated by friends, she crafted delicate sculptures that hang from the ceiling by fishing line. White’s materials are both ordinary and tragic, and her sculptures, which should be depressing, are transcendent. She manages to critique social norms while also creating something beautiful and even hopeful.

Indeed, what’s compelling about “The Myth of Normal” is that it doesn’t just critique society; it also proposes an alternate vision for the future. The show argues art—something that should and can be accessible to everybody—can help us heal old traumas and build a healthier society. Perhaps, if we’re lucky, this way of being and making will become the new normal.

“The Myth of Normal: A Celebration of Authentic Expression” is on view at the MassArt Art Museum through May 19, 2024.