“The Sun Rises in the West and Sets in the East” at Tufts University Art Galleries is an exhibition of work by eleven contemporary artists on planetary reversals and inversions—of language, signs and symbols, geopolitical worldviews, and ideological trajectories. The show’s title alone prompts several disorientations, not only to our cosmic alignment, but also to the very geographical abstractions of the “East” and “West” and to colonial distinctions of the “Orient” and “Occident” that echo amid a political, economic, and military “rise of the East.” According to Sara Raza (curator of the exhibition and author of the forthcoming book Punk Orientalism: The Art of Rebellion), this project is not about negating dichotomies, but rather about what can happen when such relational poles are worked through in nuanced ways. Drawing its title from a phrase that recurs across Islamic cosmologies—including as a portent of the last judgment in the Quran—“The Sun Rises in the West and Sets in the East” follows an interconnected world plunged into darkness and decline. Through the cyclical framework of reversal, the exhibition ultimately prompts various shifts in perspective regarding worlds ending. As these works propose, it is among the ruins that new possibilities of being may arise.

Starting on the first-floor space, the exhibition opens with two large copper panels punctured by what look to be hundreds of nails, which form two diamond shapes that each enclose a cross. These iconic works by Nari Ward feature a series of Kongo cosmograms, prayer symbols of both sacred and harrowing proportions. It was in an eighteenth-century church in Georgia that the artist first encountered the distinctive shapes drilled into the floorboards, under which enslaved people hid and were given ventilation to breathe as they fled along the Underground Railroad. In these works, Ward reclaims the ancestral and spiritual significance of the cosmogram as embodying the cycle of life, death, and rebirth while considering the healing properties of copper itself—an apt initiation to the show. On the opposite wall, a row of watercolors depicting bird taxidermies by Ali Cherri entitled Dead Inside (2020) also looks beyond existing dichotomies of life and death to reflect on, and cope with, an internal state of lived experience after trauma. For the Beirut-born, Paris-based artist, feeling “dead inside” while alive can become the basis for a shared poetics of loss, including for those of the diaspora.

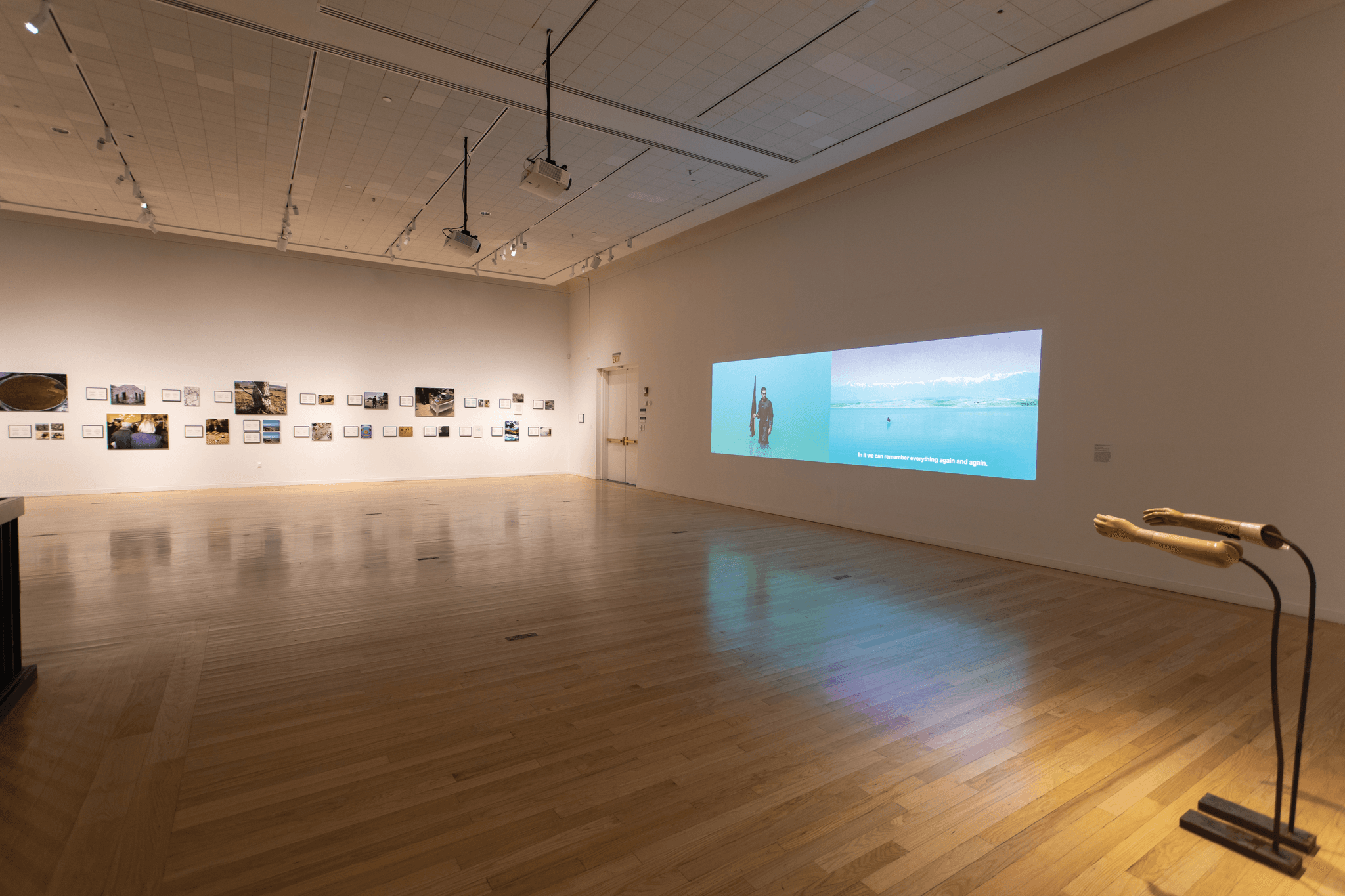

The transformative framework of diaspora is also one that animates the exhibition as a whole, beginning with the artists’ own migrations across often several geographies, nation-states, cultures, and worldviews. A disembodied pair of prosthetic arms mounted on steel poles by Algerian-French artist Kader Attia extend outwards as if looking for an embrace. While such prosthetics refer to both the physical impacts of colonial domination across the world (survivors of war are often amputees), in the context of this exhibition, the phantom limb made corporeal through the prosthetic also becomes a metaphor for thinking about displacement and diaspora—the psychological manifestation of missing a part of your very being that’s no longer there.

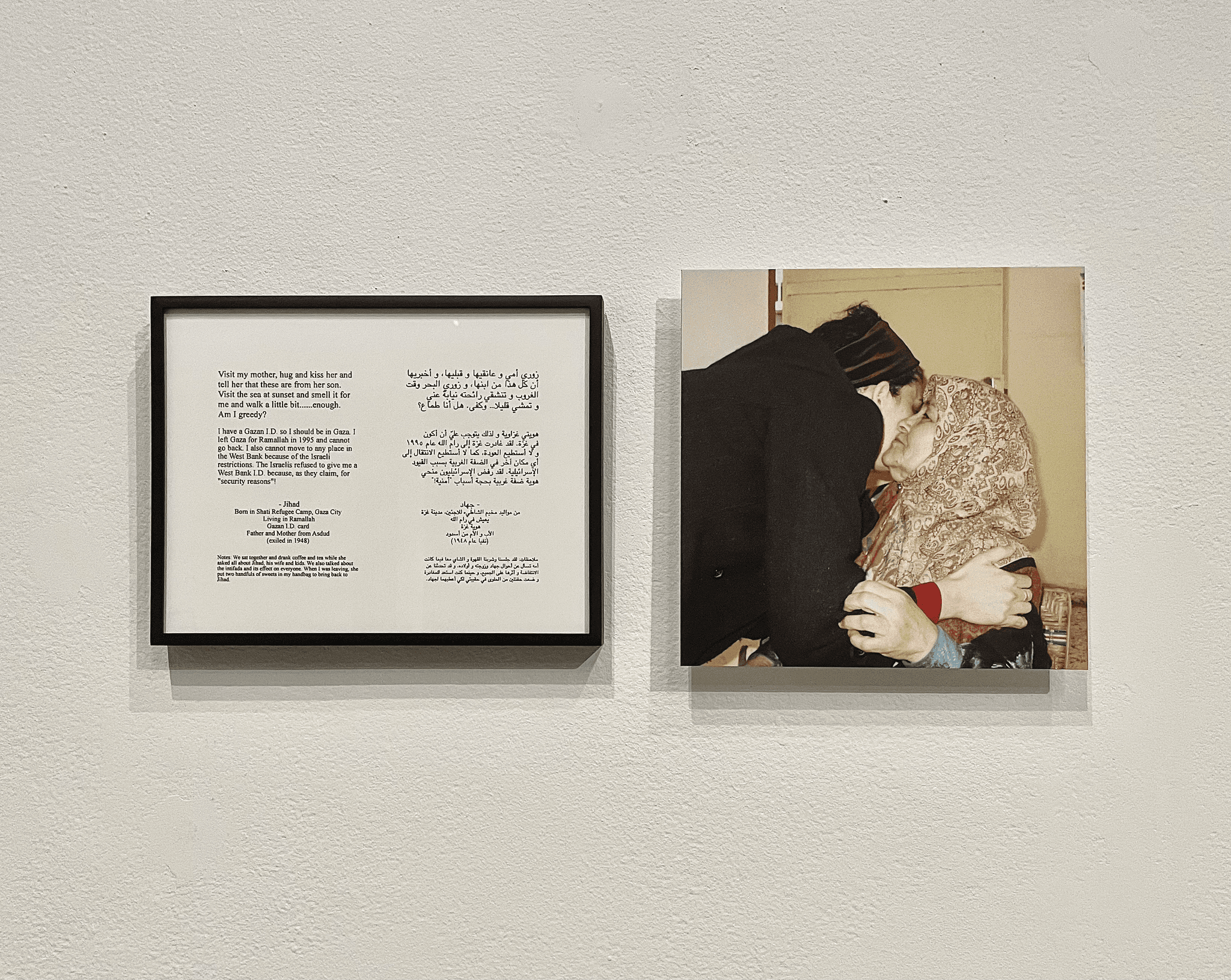

It seems poignant that these empty arms extend towards Emily Jacir’s photo and text documentation series Where We Come From (2001–2003). Perhaps the most moving of the works in this exhibition, the project features a selection of thirty responses to a question posed by the artist to displaced Palestinians across the world: “If I could do anything for you, anywhere in Palestine, what would it be?” The responses range from “drink the water in my parents’ village” to “go to my mother’s grave in Jerusalem on her birthday and put flowers and pray.” Jacir, who holds a passport that allows her to move freely between territories, executes each request and photographs each encounter. The pairing of text and image here amplifies the poetic as well as political nature of such border crossings on behalf of others. Each becomes a kind of relational portraiture of exile, longing, despair, and also love, simplicity, and kinship that both comprises and connects each individual within a dispersed diaspora.

In a large-scale two-channel projection by Lida Abdul, a man stumbles into a lake outside of Kabul while struggling to keep a flag high above his head and the crystalline water in an act of nationalist dedication. As Abdul shows in What We Have Overlooked (2011) with visually stunning simplicity, what is at stake in terms of national unity, as represented by the flag, is the life of the individual. As viewers, we’re further implicated by the surveillance-like quality of the footage that captures the man at various angles and distances—a live sacrifice happens before our eyes as he sinks beneath the waters and never resurfaces. With no more bearer, the flag follows closely behind until only the sublime landscape and mountains remain. As What We Have Overlooked suggests, perhaps what we have overlooked entirely in favor of geopolitical ideology is the world.

The fate of a nation-state, as represented by four stacks of satirical newspapers in front of a couched seating area in Aslı Çavuşoğlu’s Future Tense (2017), is told through fifty fortune-tellers, astrologers, and other soothsayers’ diverse prophecies predicting the political future of Turkey and the world. Among the many headlines, one reads “WOMEN TO SAVE THE FUTURE…There is a thick snake, like a cobra, which is stealthily moving from the West to the East…” With governmental crackdowns on freedom of the press and increasing censorship in mind, viewers are encouraged to take a newspaper, which disguises hidden “truths” as clairvoyance while expanding on the gray area between speculative fiction and fact.

Across from Çavuşoğlu’s newspaper installation, what sounds like a propaganda speech emanates faintly from a black-box space. And indeed Yael Bartana appropriates both the style of Nazi nationalist propaganda and early Zionist films in Mary Koszmary (Nightmares) (2007), a work that invites Jews to return to Poland while reflecting on complex Polish-Jewish relations. The speaker Sławomir Sierakowski (real-life leader of a Polish leftist group) at first seems to be a lone apocalyptic figure at the bottom of an overgrown Tenth Anniversary Stadium in Warsaw, pleading to a few caravans that have made camp atop its periphery. As his earnest and poetic speech progresses, however, the camera pans out to the field, revealing a group of children spelling out “3,300,000 Jews can change the lives of 40,000,000 Poles.” In concluding lines—“Return, and we shall finally become Europeans. There is no future for chosen peoples. There is no future for peoples in general. Instead of identical, let us become one”—Sierakowski calls for a unification that would transform Europe from the inside out by embracing difference. He and the children walk out of the stadium, holding up small Polish flags, smiling hopefully.

The burning of modernist forms constitutes a critical rebirth of meaning and materiality in Anton Ginzburg’s Burnt Constructions. Gushul Initiative (2016), based on Russian Constructivist Alexander Rodchenko’s Spatial Studies. Ginzburg applies what was historically a radically rational art for a society born of the Russian Revolution to a contemporary North American context (in Alberta, Canada). The work gives new meaning not only to productivist art, but also inverts the idea of “production” as endless growth, inherited from the modernist era of steel and concrete. These singed structures made of wood are rather creations born of destruction, both conceptual and material.

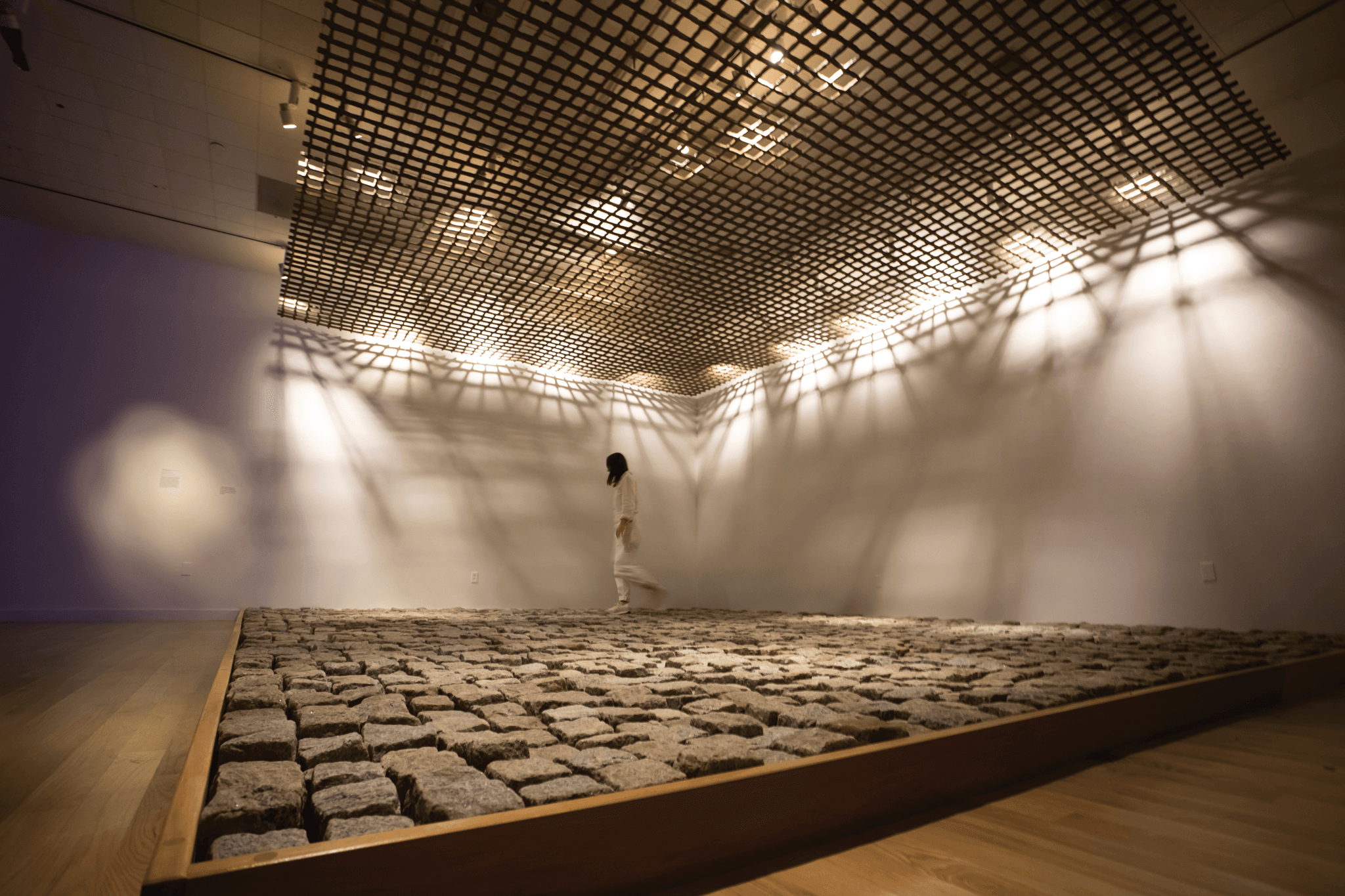

The steady sounds of underwater breathing lead to the lower-level galleries and an encounter with Ergin Çavuşoğlu’s immersive video work Lundy, Louis, Barge and Troy (2014), which emerges from the dark as a two-channel installation featuring a World War I shipwrecked fleet (seen from above) in parallel to the contemporary vessels traversing the blue waters like shadows from above (seen from below). The continuous dissolution of empire is evident in these mirrored images featuring different temporalities of imperialist maritime ruin and new ruins in the making. Lastly, Nadia Kaabi-Linke’s Road Works (Remont II) (2021), recreates a cobblestone pavement in Kyiv, Ukraine within the gallery space, to reflect on personal histories of migration and border crossing, as well as an endless cycle of crisis and reparation that draws from the work’s title. Not easily translated, the Ukrainian word remont gestures toward an endless state of less-than-optimal renovations grounded in a place, such as to a road by the local people who travel it every day. Kaabi-Linke translates this precarious installation of unfixed stone into an embodied experience rather than one of voyeuristic artifact, on which viewers are invited to walk across its unstable surface and reflect on their own simultaneous crossing of borders and rootedness.

What emerges from not the West’s self-image (that creates the East), but rather from its epistemological collapse and subsequent ruin? “The Sun Rises in the West and Sets in the East” leaves room for questions and knowledge production turned upside down and inside out. In this way, the exhibition also strikes as a long-term, research-rich endeavor with its “faculty voice” wall labels and online guide containing resources on “artists in the exhibition,” “themes,” and “background,” reflecting both the pedagogical nature of Tufts’s exhibitions and Raza’s own practice. Further guiding inquiries include “What is lost by a reliance on mainstream/Western information streams? How can we counter our colonial knowledge with other forms of knowledge?” While retracing my steps and exiting past Nari Ward’s copper works with such inquiries in mind, their glowing Kongo cosmograms seem to express another kind of presence. The formations—celestial, divine, alien, otherworldly—hang like a prophecy and promise over a hazy breaking of sky.

“The Sun Rises in the West and Sets in the East” is on view at Tufts University Art Galleries (Medford) from August 30 to December 11, 2022.