Online Only• Jan 22, 2024

Christian Walker: Thoroughly Political, Poignant, and Worthy of Further Exploration

Opening this week at Tufts University Art Galleries after being on view at the Leslie-Lohman Museum in Manhattan, this first museum retrospective of the late Walker’s career as a photographer illuminates his life as a queer artist, activist, and intellectual in Boston and Atlanta.

Review by Marcus Civin

(left three) Christian Walker, "Mule Tales" series, 1990–95. (right three) Christian Walker, "Vivisections" series, 1993. Installation view, “Christian Walker: The Profane and the Poignant,” curated by Jackson Davidow and Noam Parness (Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York, September 22, 2023–January 7, 2024). Photograph by Object Studies. © 2023 Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York.

(left three) Christian Walker, "Mule Tales" series, 1990–95. (right three) Christian Walker, "Vivisections" series, 1993. Installation view, “Christian Walker: The Profane and the Poignant,” curated by Jackson Davidow and Noam Parness (Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York, September 22, 2023–January 7, 2024). Photograph by Object Studies. © 2023 Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York.

A blue-toned photograph from 1993 shows a pensive, backward-glancing child. It seems to matter that this is a Black child, that this is a boy. A silkscreened paragraph runs over his face. This text doesn’t directly match the image. Written in first person, it laments falling in very adult love with handsome hustlers described in short phrases or with single words set off by full stops, the hustlers characterized as abusive but elegant, tattooed, and muscular. They carry syringes. They’re confused and angelic. Sometimes their bodies resemble children’s bodies. “Experts of injection. Champions of sexual positions,” the text reads. “HIV positive. Vacated. Vanished. Vaporized.”

This harrowing silkscreened text becomes a curse, an eerie prediction, and a reminder about borrowed time and the gangly boys sometimes kicking around inside stoic men. This photograph from Christian Walker’s Vivisections series is one of the final works in a properly elegiac retrospective that traveled to the Tufts University Art Galleries from the Leslie-Lohman Museum in Manhattan, which has a mission to support, exhibit, and preserve LGBTQIA+ art. The Walker photograph may be among the last surviving works by the artist—dead at the age of fifty in a Seattle halfway house in 2003, allegedly from a drug overdose. Although he made photographs until his untimely end, the exhibition wall text suggests that most of his latest works haven’t resurfaced. Before the halfway house, Walker was in dire straits, living on the streets. It sounds like maybe someone at the halfway house threw away his photos and personal effects after he died. Still, his ruthlessly sharp analysis—or vivisection—calls to mind other contemporaneous fulminations, like David Wojnarowicz’s powerful Untitled (One Day This Kid), an edition from 1990 where the boy depicted is Wojnarowicz and the text around him predicts the hatred and violence the artist knew he would experience soon after he discovered his desire for other boys’ bodies. Wojnarowicz wrote: “One day this kid will do something that causes men who wear the uniforms of priests and rabbis, men who inhabit certain stone buildings, to call for his death.”

Christian Walker, From The Theater Project, 1983-4. Gelatin silver print. 11′ x 14′. Collection of David VanHoy.

Walker’s vivisection also echoes writing included in his 1985 book The Theater Project, which documented nights at a grand, deteriorating, and controversial downtown Boston theater, the Pilgrim, where—before Boston became one of the most gentrified cities anywhere—men and sometimes trans women would cruise and have sex. Walker called the Pilgrim “a contemporary urban temple” and described some of the faithful: romance-seekers, married men, students, and a young man from Florida who stayed for almost a week, sustaining his pleasure and scrounging from vending machines. In the theater, according to Walker, hardly anyone spoke. It smelled. On cold nights, the ticket-taker would open a door for anyone seeking warmth. Despite the freedom, solace, and beauty it contributed to, despite its foregrounding of desire and the respite it provided from hatred, Walker found in the Pilgrim a melancholy palace, profane and poignant, “where the pervasive aloneness of the outside world is crystallized, sharp-focused, made painful and jewel-like.”

“Christian Walker: The Profane and the Poignant” provides a chronological exploration of Walker’s career as a photographer and illuminates his life as an artist and intellectual. Active in Boston and Atlanta, Walker grew up in Springfield, Massachusetts, where he felt isolated. He moved to Boston in 1974, in his early twenties, took odd jobs, eventually wrote for a radical gay newspaper, and around 1979 started making black-and-white Diane Arbus–influenced portraits of friends, family, members of the Fort Hill Faggots for Freedom, and residents of a group home for people with special needs where he worked the night shift. Walker attended the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, from 1980 to 1984, and he worked voraciously over his less than two-decade career with portraiture, street photography, rephotography, and unconventional photographic techniques, including applying ink, pigments, and varnish to photographs. Part of a zeitgeist at the time coursing through the Museum School and foregrounding sexual liberation and experimental photography, Walker has not previously been considered a part of the Boston School, but he exhibited in at least one group show with Mark Morrisroe, the unofficial leader of the informal group, and he may have crossed paths with kindred spirit Nan Goldin.

Elizabeth Turk, C. W. _ Summer 1992, 1992. Gelatin silver print, 9.5″ x 11.25″. © the artist.

Jackson Davidow and Noam Parness curated “Christian Walker: The Profane and the Poignant,” coming together out of a shared interest in sustaining histories of activism and gay liberation. Davidow, who is from Boston, penned a 2021 article in The Baffler titled “Against Our Vanishing: Cruising the Queer Archives of a Disappeared Boston,” which articulates much of the guiding spirit of the exhibition. “One of the first Black gay photographers, anywhere, to make openly queer work about his own experience,” Davidow wrote, “Walker died in poverty and obscurity. His devastating story coincides with a shameful pattern of Black queer artists being erased from the history of art.” Since no archive, gallery, or estate currently looks after Walker’s legacy, the show is his strongest advocate, and it implies the need for more research. Davidow and Parness hope the Boston iteration will lead to more of his art coming out of the woodwork. Perhaps, too, an Atlanta venue would be meaningful and helpful in a similar regard. Maybe, too, a printed catalog?

Christian Walker, Performance Counts series, c. 1987–88. Installation view, “Christian Walker: The Profane and the Poignant,” curated by Jackson Davidow and Noam Parness (Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York, September 22, 2023–January 7, 2024). Photograph by Object Studies. © 2023 Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York.

I caught up with the curators on a video call after the show had just arrived in Boston from Manhattan. They described a companion exhibition also on view at Tufts, “As the World Burns: Queer Photography and Nightlife in Boston,” curated by Davidow with Laurel McLaughlin, which helps contextualize Walker’s investigation of art, life, and queer community in the ’70s and ’80s. I asked why, despite his brilliance, Walker isn’t now better known. “We’re accustomed to art histories revolving around New York, London, or Los Angeles,” Davidow replied. “Places like Boston and Atlanta are more sidelined even if in a lot of ways they have art histories that merit exploration.… Art history is keen to create these narratives that pivot around one, two, or three people. There’s [already] a canon of Black gay male art history.”

The scope of the roughly seventy works on view is bracing. In a brown ink-and-oil-agitated print from the Performance Counts series (1987–1988), a Black child in suspenders cups his ear and looks up at an ominous sky. Meanwhile, in a haunting series of double-exposure photographs, Bargaining with the Dead (1986–1989), Walker mixes representations of iconographic figures with images of his family. An earlier photograph Walker took between 1979 and 1983 in the neighborhood around the Pilgrim, Boston’s former red light district known as the Combat Zone. It shows a woman clutching a boy reaching out toward what is likely a porn theater while a man probably just a decade older goes inside. Of two extant reminders of the undated Self-Portrait at 26 with White Boys, one is a reproduction in a magazine, the other a partial print, just the top half, possibly a test for what is referred to and represented in the magazine as a likely now lost larger two-part version. Even here in pieces, strong leggy lines define an interracial low-mattress rollick laid out like two sandwiched-together comic strips to take on the proportions of a movie screen. The figures’ heads are off-camera, but we get jeans, sunglasses on the floor, dicks in hands—everything stark against white sheets and gray carpet.

Christian Walker, Untitled (Boston’s Combat Zone), c. 1979–83. Gelatin silver print, 6.25″ x 9″. Collection of David VanHoy.

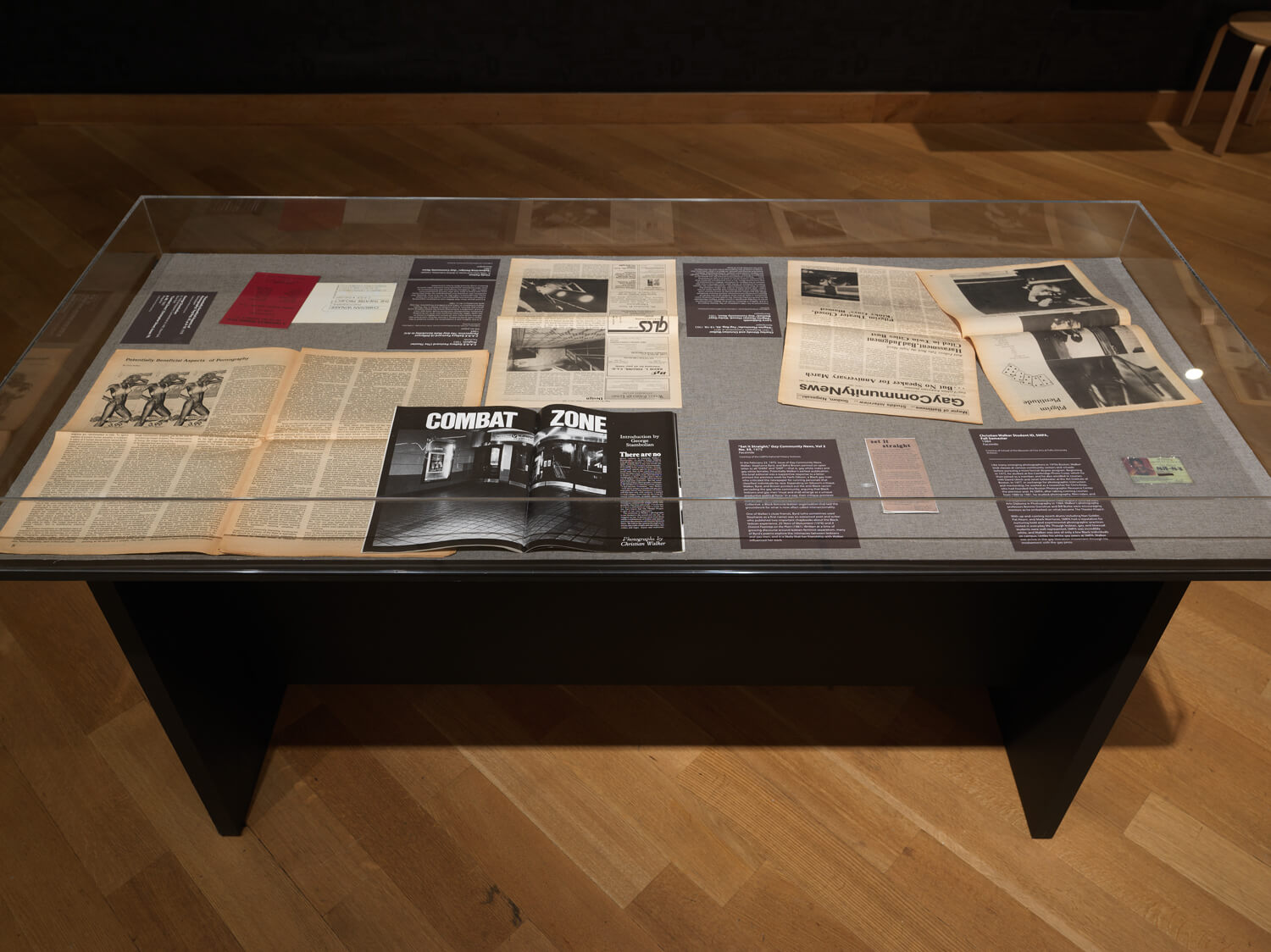

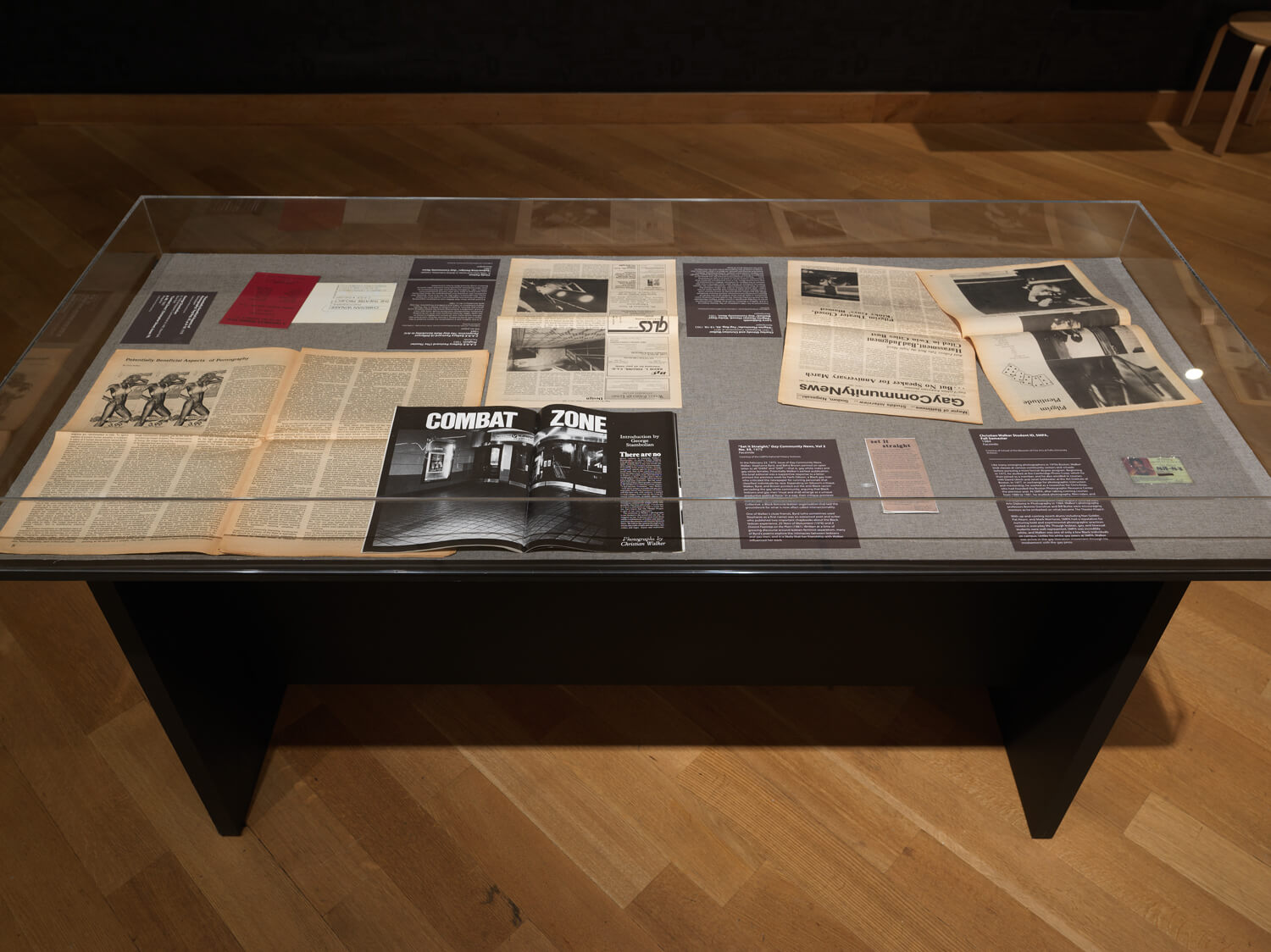

Throughout the exhibition are photographs of Walker taken by friends—his collector Roger Bakeman, the Georgia-based artist and academic V. Elizabeth Turk, and Bill Burke, an important and supportive teacher for Walker, Goldin, and others at the Museum School. There are also museum cases chock-full of historical ephemera. One case holds a 1975 letter co-signed by Walker in Boston’s Gay Community News decrying racism in the community. In another case, there’s a 1990 interview Walker conducted with the artist Andres Serrano for Art Papers. Serrano, attacked for using bodily fluids and religious subject matter, stated his aversion to what he called homogenized, non-threatening art. Nearby, there’s material associated with a 1990 exhibition Walker co-curated in Atlanta titled “Against the Tide: The Homoerotic Image in the Age of Censorship and AIDS.” There’s also Junkies Don’t Care About Bleach, Walker’s 1989 work made in collaboration with a person identified as Bobby who wrote about how he was trying to think more about who he shared needles with and took as sexual partners.

Installation view, “Christian Walker: The Profane and the Poignant,” curated by Jackson Davidow and Noam Parness (Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York, September 22, 2023-January 7, 2024). Photograph by Object Studies. © 2023 Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York.

Walker’s resume is impressive. During his lifetime, he participated in landmark exhibitions—“Black Male,” curated by Thelma Golden at the Whitney in 1994; the traveling show “Black Photographers Bear Witness: 100 Years of Social Protest,” curated by Deborah Willis in 1989; and, spread out across multiple New York venues, “The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s.” In her book Black Looks: Race and Representation (1992), bell hooks quoted Walker on her way to demanding that all people engage with “the militant struggle by Black folks to transform the image.”

The Leslie-Lohman show was a revelation—heartbreaking and transcendent. I can only imagine it will be even more resonant for Boston audiences who might know some of Walker’s psychic geography. It seems to me the predominant concern of Walker’s weighty body of work is how photographs contribute to constructions of identity and how people interact, face off, remain alone, intermingle, or establish intimacy, especially in contexts where racism and homophobia are pervasive. Walker’s art keeps pain, life, youth, yearning, and death pressed up against each other, sometimes inscribed on the same face or in an embrace. I think it’s work especially worthy of further exploration.

“Christian Walker: The Profane and the Poignant” is on view at Tufts University Art Galleries, SMFA at Tufts, January 24–April 21, 2024.